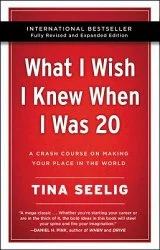

What I Wish I Knew When I Was 20: A Crash Course on Making Your Place in the World

Tina Seelig—2009.

Chapter 1 BUY ONE GET TWO FREE

- What would you do to earn money if all you had was five dollars and two hours? This is the assignment I gave students in one of my classes at Stanford University Each of fourteen teams received an envelope with five dollars of “seed funding” and was told they could spend as much time as they wanted planning. However, once they cracked open the envelope; they had two hours to generate as much money as possible. I gave them from Wednesday afternoon until Sunday evening to complete the assignment. Then, on Sunday evening, each team had to send me one slide describing what they had done, and on Monday afternoon each team had three minutes to present their project to the class. They were encouraged to be entrepreneurial by identifying opportunities, challenging assumptions, leveraging the limited resources they had, and by being creative.

- How did they do this? Here’s a clue: the teams that made the most money didn’t use the five dollars at all. They realized that focusing on the money actually framed the problem way too tightly. They understood that five dollars is essentially nothing and decided to reinterpret the problem more broadly: What can we do to make money if we start with absolutely nothing? They ramped up their observation skills, tapped into their talents, and unlocked their creativity to identify problems in their midst—problems they experienced or noticed others experiencing—problems they might have seen before but had never thought to solve. These problems were nagging but not necessarily at the forefront of anyone’s mind. By unearthing these problems and then working to solve them, the winning teams brought in over $600, and the average return on the five dollar investment was 4,000 percent! If you take into account that many of the teams didn’t use the funds at all, then their financial returns were infinite.

- So what did they do? All of the teams were remarkably inventive. One group identified a problem common in a lot of college towns—the frustratingly long lines at popular restaurants on Saturday night. The team decided to help those people who didn’t want to wait in line. They paired off and booked reservations at several restaurants. As the times for their reservations approached, they sold each reservation for up to twenty dollars to customers who were happy to avoid a long wait.

- As the evening wore on, they made several interesting observations. First, they realized that the female students were better at selling the reservations than the male students, probably because customers were more comfortable being approached by the young women. They adjusted their plan so that the male students ran around town making reservations at different restaurants while the female students sold those places in for line. They also learned that the entire operation worked best at restaurants that use vibrating pagers to alert customers when their table is ready. Physically swapping pagers made customers feel as though they were receiving something tangible for their money. They were more comfortable handing over their money and pager in exchange for the new pager. This had an additional bonus—teams could then sell the newly acquired pager as the later reservation time grew nearer.

- Another team took an even simpler approach. They set up a stand in front of the student union where they offered to measure bicycle tire pressure for free. If the tires needed filling they added air for one dollar. At first they thought they were taking advantage of their fellow students, who could easily go to a nearby gas station to have their tires filled. But after their first few customers, the students realized that the bicyclists were incredibly grateful. Even though the cyclists could get their tires filled for free nearby, and the task was easy for the students to perform, they soon realized that they were providing a convenient and valuable service. In fact, halfway through the two hour period, the team stopped asking for a specific payment and requested donations instead. Their income soared. They made much more when their customers were reciprocating for a free service than when asked to pay a fixed price. For this team, as well as for the team making restaurant reservations, experimenting along the way paid off. The iterative process. Where small changes are made in response to customer feedback, allowed them to optimize their strategy on the fly.

- Each of these projects brought in a few hundred dollars. And their fellow classmates were duly impressed. However, the team that generated the greatest profit looked at the resources at their disposal through completely different lenses, and made $650. These students determined that the most valuable asset they had was neither the five dollars nor the two hours. Instead, their insight was that their most precious resource was their three-minute presentation time on Monday. They decided to sell it to a company that wanted to recruit the students in the class. The team created a three-minute “commercial” for that company and showed it to the students during the time they would have presented what they had done the prior week. This was brilliant. They recognized that they had a fabulously valuable asset—that others didn’t even notice—just waiting to be mined.

- I count the “Five-Dollar Challenge” as a success in teaching students about having an entrepreneurial mind-set. But it left me feeling a bit uncomfortable. I didn’t want to communicate that value is always measured in terms of financial rewards. So, I added a twist the next time I assigned the project. Instead of five dollars, 1 gave each team an envelope containing ten paper clips. Teams were told they had four hours over the next few j days to generate as much “value” as possible using the paper clips, where value could be measured in any way they wanted. The inspiration for this was the story of Kyle MacDonald, who started with one red paper clip and traded up until he had a house. He set up a blog to document his progress and to solicit trades. It took a year, but step-by-step he reached his goal. He traded the red paper clip for a fish-shaped pen.

- Just before I fainted, they announced that they were joking and showed another video documenting what they really had done. They traded the paper clips for some poster board and set up a stand at a nearby shopping center with a sign that read. “Stanford Students For Sale: Buy One, Get Two Free.” They were amazed by the offers they received. They started out carrying heavy bags for shoppers, moved on to taking out the recycling from a clothing store, and eventually did an ad hoc brainstorming session for a woman who needed help solving a business problem. She paid them with three computer monitors she didn’t need.

- This exercise ultimately evolved into what has become known as the “Innovation Tournament,” with hundreds of teams from all over the world participating. In each case, participants use the competition as a means to look at the world around them with fresh eyes, identifying opportunities in their own backyard. They challenge traditional assumptions, and in doing so generate enormous value from practically nothing. The entire adventure with Post-it notes was captured on film and became the foundation for a professional documentary called Imagine It.

- The exercises described above highlight several counterintuitive points. First, opportunities are abundant. At any place and time you can look around and identify problems that need solving.

- Second, regardless of the size of the problem, there are usually creative ways to use the resources already at your disposal to solve them. This is actually the definition many of my colleagues use for entrepreneurship: an entrepreneur is someone who is always on the lookout for problems that can be turned into opportunities and finds creative ways to leverage limited resources to reach their goals

- Third, we so often frame problems too tightly. When given a simple challenge, such as earning money in two hours, most people quickly jump to standard responses. They don’t step back and look at the problem more broadly. Taking off the blinders opens up a world of possibilities. Students who participated in these projects took this lesson to heart. Many reflected afterward that they would never have an excuse for J being broke, since there is always a nearby problem begging to be solved.

- I focus first on individual creativity, then move on to creativity in teams, and finally dive into creativity and innovation in large organizations.

- STVP focuses on teaching, scholarly research, and outreach to students, faculty, and entrepreneurs around the world. We strive to create “T-shaped people,” those with a depth of knowledge in at least one discipline and a breadth of knowledge

- All d.school courses are taught by at least two professors from different disciplines, and cover an endless array of topics, from design for extreme affordability to creating infectious action to design for agile aging.

- In sharp contrast, in most situations outside of school there are a multitude of answers to every question, many of which are correct in some way. And, even more important, it is acceptable to fail. In fact, failure is an important part of life’s learning process. Just as evolution is a series of trial-and-error experiments, life is full of false starts and inevitable stumbling.

Chapter 2 THE UPSIDE-DOWN CIRCUS

- Later that afternoon the CEO of a company approached me and lamented that he wished he could go back to school, where he would be given open-ended problems and be challenged to be creative. I looked at him with confusion. I’m pretty confident that every day he faces real-life challenges that would benefit from creative thinking.

- Attitude is perhaps the biggest determinant of what we can accomplish. True innovators face problems directly and turn traditional assumptions on their head.

- Lance Armstrongs Live Strong bracelets. Do Bands have a few guiding principles:

- Put one around your wrist with a promise to do something.

- Take it off when you have completed the task.

- Record your success online at the Do Bands Web site Each Do Band comes with a number printed on it so you can look up all the actions it has inspired.

- Pass the Do Band along to someone else.

- Assign a simple challenge in my class, using a related concept, that’s designed to give students experience looking at obstacles in their lives from a new perspective. I ask them to identify a problem, and then pick a random object in their environment. They then need to figure out how that object will help them solve the problem. Of course, I have no notion about their personal challenges, what objects they will select, or whether they will successfully solve their problem.

- My favorite example is a young woman who was moving from one apartment to another. She had to transport some large furniture and had no idea how to make it happen. If she couldn’t move the furniture, she would have to leave it in her old apartment. She looked around her apartment and saw a case of wine that was left over from a party a few weeks earlier. Aha! She went to craigslist®, an online community bulletin board, and offered to trade the case of wine for a ride across the Bay Bridge with her furniture. Within a few hours, all of her furniture was moved. The leftover wine collecting dust in the corner had been transformed into valuable currency. The assignment didn’t turn the wine into currency, but it did give this woman the ability and motivation to see it that way.

- The key to need finding is identifying and filling gaps—that is, gaps in the way people use products, gaps in the services available, and gaps in the stories they tell when interviewed about their behavior.

- Michael realized that Kimberly-Clark was missing the point: they were selling diapers as though they were hazardous waste disposal devices. But parents don’t view them that way to a parent; a diaper is a way to keep their children comfortable. Dealing with diapers is part of the nurturing process. A diaper is also viewed as a piece of clothing. These observations provided a great starting point for improving how. Kimberly packaged and positioned Huggies. Then, upon closer scrutiny, Michael identified an even bigger opportunity. He noticed that parents become terribly embarrassed when asked if their child is “still in diapers.” Bingo! This was a huge pain point for parents and for kids on the cusp of toilet training. There had to be a way to turn this around. How could diaper become a symbol of success as opposed to failure? Michael came up with the idea for Pull-Ups®, a cross between a diaper and underwear. Switching from diapers to Pull-Ups served as a big milestone for both children and parents. A child can put on a Pull-Up without help, and can feel proud of this accomplishment. This insight led to a billion-dollar increase in annual revenue for Kimberly-Clark and allowed them to leapfrog ahead of their competition. This new product grew out of focused need finding, identification of a clear problem and then turning it an opportunity.

- Once you get the hang of it, this is an easy, back-of-the envelope exercise you can use to reevaluate all aspects of your life and career. The key is to take the time to clearly identify every assumption. This is usually the hardest part, since, as described in the case about balloon angioplasty, assumptions are sometimes so integrated into our view of the world that it’s hard to see them.

- This message is echoed by author Guy Kawasaki, who says it is better to “make meaning than to make money.”’ If your goal is to make meaning by trying to solve a big problem in innovative ways, you are more likely to make money than if you start with the goal of making money, in which case you will probably not make money or meaning.

- By the end of a week’s worth of challenging activities including scouring newspapers to identify problems, brainstorming to come up with creative solutions, designing new ventures, meeting with potential customers, filming commercials, and pitching their ideas to a panel of successful executives, they were ready to take on just about any challenge.

Chapter 3 BIKINI OR DIE

- Larry Page, co-founder of Google, gave a lecture in which he encouraged the audience to break free from established guidelines by having a healthy disregard for the impossible. That is, to think as big as possible. He noted that it is often easier to have big goals than to have small goals. With small goals, there are very specific ways to reach them and more ways they can go wrong. With big goals, you are usually allocated more resources and there are more ways to achieve them.

- Linda Rottenberg is a prime example of a person who sees no problem as too big to tackle and readily breaks free of expectations in order to get where she wants to go. She believes that if others think your ideas are crazy, then you must be on the right track. Eleven years ago Linda started a remarkable organization called Endeavor. Their goal is to foster entrepreneurship in the developing world. She launched Endeavor just after graduating from Yale Law School, with little more than a passion to stimulate economic development in disadvantaged regions. She stopped at nothing to reach her goals, including “stalking” influential business leaders whose support she needed. Endeavor began its efforts in Latin America and has since expanded to other regions of the world, including Turkey and South Africa. They go through a rigorous process to identify high-potential entrepreneurs and, after selecting those with great ideas and the drive to execute their plan, give them the resources they need to be successful. The entrepreneurs are not handed money, but instead are introduced to those in their environment who can guide them

- They are also provided with intense educational programs, and get an opportunity to f meet with other entrepreneurs in their region who have navigated the circuitous path before. Once successful, they serve as positive role models; create jobs in their local communities. And, eventually, give back to Endeavor, helping future generations of entrepreneurs.

- The next exercise forces people to do this in a surprising way first, come up with a problem that is relevant for the particular group. For example, if it is a group of executives in the utility business. The topic might be getting companies to save energy; if it is a theater group, the problem might be how to attract a larger audience; and if it is a group of business students, the challenge might be to come up with a cool, new business idea. Break the group into small teams and ask each one to come up with the best idea and the worst idea for solving the stated problem. The best idea is something that each team thinks will solve the problem brilliantly. The worst idea will be ineffective, unprofitable, or will make the problem worse. Once they are done, for they write each of their ideas on a separate piece of paper, one labeled BEST and one labeled WORST. When I do this exercise, I ask participants to pass both to me, and I proceed to shred the BEST ideas. After the time they spent generating these great ideas, they are both surprised and not too happy. I then redistribute the WORST ideas. Each team now has an idea that another team thought was terrible. They are instructed to turn this bad idea into a fabulous idea. They look for at the horrible idea that was passed their way and quickly see that it really isn’t so bad after all. In fact, they often think it is terrific. Within a few seconds someone always says, “Hey, this is a great idea!

- The group given the challenge of starting a heart attack museum used this idea as the starting point for a museum devoted entirely to health and preventative medicine.

- This exercise is a great way to open your mind to solutions to problems because it demonstrates that most ideas, even if they look silly or stupid on the surface, often have at least a seed of potential. It helps to challenge the assumption that ideas are either good or bad, and demonstrates that, with the right frame of mind, you can look at most ideas or situations. And find something valuable.

- Patricia Ryan Madson, who wrote Improv Wisdom,

- Instead of going through – a rigorous screening process, they decided to not decide, and hired almost everyone—as interns. This gave them the chance to see each individual in action, and for the students to get a taste of the company.

- Armen realized-he had struck a nerve. He decided to build an even bigger Web site that allowed anyone to share his or her experiences anonymously

- This new site. called “The Experience Project,” gained avid users quickly Armen had to make a tough decision: Should he stay in the secure job with a reliable salary and a clear career path, or jump into the unknown by deciding to run The Experience Project full-time?

- “All the cool stuff happens when you do things that are not the automatic next step”

Chapter 4 PLEASE TAKE OUT YOUR WALLETS

- Over time, I’ve became increasingly aware that the world is divided into people who wait for others to give them permission to do the things they want to do and people who grant themselves permission. Some look inside themselves for motivation and others wait to be pushed forward by outside forces.

- Another way to anoint yourself is to look at things others have discarded and find ways to turn them into something useful. There is often tremendous value in the projects others have carelessly abandoned. As discussed previously, sometimes people jettison ideas because they don’t fully appreciate their value, or because they don’t have time to fully explore them.

- 1. It was the year 2000, and Michael saw that there was a new feature that let customers add a photo to their standard listing for an additional twenty-five cents. Only 10 percent of eBay customers were using this feature. Michael spent some time analyzing the benefits of this service and was able to demonstrate that products with accompanying photos sold faster and at a higher price than products without photos. Armed with this compelling data, he started marketing the photo service more heavily and ended up increasing the adoption rate of this feature by customers from 10 percent to 60 percent. This resulted in $300 million in additional annual revenue for eBay. Without any instructions from others, Michael found an untapped gold mine and exploited it with great results. The cost to the company was minimal and the profits were profound.

- There is considerable research showing that those willing to stretch the boundaries of their current skills and willing to risk trying something new, like Debra Dunn and Michael Dearing, are much more likely to be successful than those who believe they have a fixed skill set and innate abilities that lock them into specific roles. Carol Dweck, at Stanford’s psychology department, has written extensively about this, demonstrating that those of us with a fixed mind-set about what we’re good at are much less likely to be successful in the long run than those with a growth mind-set.

- So how do you find holes that need to be filled? It’s actually quite simple. The first step is learning how to pay attention.

- My colleagues at the d.school developed the following exercise, which gets at the heart of identifying opportunities. Participants are asked to take out their wallets. They then break up into pairs and interview one another about their wallets. They discuss what they love and hate about their wallets, paying particular attention to how they use them for purchasing and storage.

- One of the most interesting insights comes from watching each person pull out his or her wallet at the beginning. Some of the wallets are trim and neat, some are practically exploding with papers, some are fashion statements, some carry the individual’s entire library of photos and receipts, and some consist of little more than a paper clip. Clearly, a wallet plays a different role for each of us. The interview process exposes how each person uses his or her wallet, what it represents, and the strange behaviors each has developed to get around the wallet’s limitations. I’ve never seen a person who is completely satisfied with his or her wallet: there is always something that can be fixed. In fact, most people are walking around with wallets that drive them crazy in some way. They discuss their frustrations with the size of their wallets, their inability to find things easily, or their desire to have different types of wallets for different occasions.

- After the interview process, each person designs and builds a new wallet for the other person—his or her “customer.” The design materials include nothing more than paper, tape. Markers, scissors, paper clips, and the like. They can also use whatever else they find in the room. This takes about thirty minutes. After they’ve completed the prototype, they “sell” it to their customer. Almost universally, the new wallet solves the biggest problems with which the customer was struggling. They’re thrilled with the concept and say that if that wallet were available, they would buy it. Some of the features are based on science fiction, such as a wallet that prints money on demand, but some require little more than a good designer to make them feasible right away.

- Many lessons fall out of this exercise. First, the wallet is symbolic of the fact that problems are everywhere, even in your back pocket. Second, it doesn’t take much effort to uncover these problems. In fact, people are generally happy to tell you about their problems. Third, by experimenting, you get quick and dirty feedback on the solutions you propose. It doesn’t take much work, many resources, or much time. And, finally, if you aren’t on the right track with a solution, the sunk cost is really low. All you have to do is start over.

- In fact, all successful entrepreneurs do this naturally. They pay attention at home, at work, at the grocery store, in airplanes, at the beach. At the doctor’s office, or on the baseball field, and find an array or opportunities to fix things that are broken.

- The consistent theme is that they each pay attention to current trends and leverage their own skills to build their influence.

- If you want a leadership role, then take on leadership roles. Just give yourself permission to do so. Look around for holes in your organization, ask for what you want, find ways to leverage your skills and experiences, be willing to make the first move and stretch beyond what you’ve done before.

Chapter 5 THE SECRET SAUCE OF SILICON VALLEY

- I require my students to write a failure resume. That is, to craft a resume that summarizes all their biggest screw ups—personal, professional, and academic. For every failure, each student I must describe what he or she learned from that experience.

- The Mayfield Fellows Program, which I co-direct with Tom Byers, a professor in Management Science and Engineering it Stanford, gives students this opportunity.” After one quarter of classroom work, during which we offer an in-depth introduction to entrepreneurship through case studies, the twelve students in this nine-month program spend the summer working in startup companies. They take on key roles in each business and are closely mentored by senior leaders in the company

- These stories highlight an important point: a successful career is not a straight line but a wave with ups and downs. Michael Dearing describes this wonderfully with a simple graph that maps a typical career, with time on the x-axis and success on the y-axis. Most people feel as though they should be constantly progressing up and to the right, moving along a straight success line. But this is both unrealistic and limiting. In reality, when you look closely at the graph for most successful people, there are always ups and downs. When viewed over a longer period of time, however, the line generally moves up and to the right.

- I am not saying that your company should reward people who are stupid, lazy, or incompetent. I mean you should reward smart failures, not dumb failures. If you want a creative organization, inaction is the worst kind of failure…Creativity results from action, rather than inaction, more than anything else.

- At the d.school there is a lot of emphasis on taking big risks to earn big rewards. Students are encouraged to think really big, even if there’s a significant chance that a project won’t be Students are told that it is much better to have a flaming failure than a so-so success. Jim Plummer, the dean of Stanford’s School of Engineering, embraces this philosophy. He tells his PhD students that they should pick a thesis project that has a 20 percent chance of success.

- www.GetBackboard.com is a Web site for collecting feedback

- All you need to do is look around to see hundreds, if not thousands, of role models for every choice I you plan to make.

Chapter 6: no way… Engineering is for girls.

- The master of the art of living makes little distinction between his work and his play, his labor and his leisure. His mind and his body, his education and his recreation. His love and his religion. He simply pursues his vision of I excellence in whatever he does, leaving others to decide whether he is working or playing. To him, he is always doing both.

- The wisdom of this is reflected in the observation that hard work plays a huge part in making you successful. And, the truth is, we simply tend to work harder at things we’re passionate about. This is easy to see in children who spend endless hours working at the things they love to do.

- When I got my paper back a week or so later a note written on the top said, “Tina, you think like a scientist.” At that moment I became a scientist. I was just waiting for someone to acknowledge my enthusiasm—and to give me permission to pursue my interests.

- From my experience, this is absolutely right. My only recommendation is that if you intend to stop working while your kids are young, consider finding a way to keep your career on a low simmer. If you haven’t stepped all the way out for too long, it’s much easier to get back in. You can do this in an infinite variety of ways, from working part-time in traditional jobs to volunteering. Not only does it keep your skills sharpened, up when you’re ready.

- Consider Karen Matthews, who has four young children and is part of a group of part-time marketing consultants. Karen takes on projects when she can, and hands them over to her partners when she’s too busy. Or take Lisa Benatar, who with young three daughters turned her attention to her children’s school. Lisa, an expert on alternative energy, started an educational program at the school that focused on teaching children about conservation.

- Taking on the puzzle of balancing work and parenting ended up being the best career decision I ever made. I wanted to be intellectually stimulated without compromising the time I had for my son. As a result, each year I evaluated how much time I needed to devote to each and found ways to take on projects that allowed me the most flexibility. I took on assignments I probably wouldn’t have considered if I didn’t have a child. I started writing children’s books, launched a Web site for science teachers, and even taught science in a private elementary school. In the long run, these experiences proved to be amazingly helpful when I did go back to work full-time. I gained credibility as a writer, learned how to design Web sites, and got valuable experience teaching—all skills I use every single day in my current role.

Chapter 7 turn lemonade into helicopters.

- Richard Wiseman, of the University of Hertfordshire in England, has studied luck and found that “lucky people” share traits that tend to make them luckier than others. First, lucky people take advantage of chance occurrences that come their way.

- They’re more likely to pay attention to an announcement for a special event in their community, to notice a new person in their neighborhood, or even to see that a colleague is in need of some extra help.

- Earlier I discuss the art of turning lemons (problems) into lemonade (opportunities). But luck goes beyond this—it’s about turning lemonade (good things) into helicopters (amazing things!)

- Echoing this point, Tom Kelley, author of The Art of Innovation, says that every day you should act like a foreign traveler by being acutely aware of your environment.

- James Barlow, the head of the Scottish Institute for Enterprise, does a provocative exercise with his students to demonstrate this point. He gives jigsaw puzzles to several teams and sets a timer to see which group can finish first. The puzzle pieces have been numbered on the back, from 1 to 500, so it’s easy to put them together if you just pay attention to the numbers. But, even though the numbers are right in front of them. It takes most teams a long time to see them, and some never see them at all. Essentially, they could easily bolster their luck just by paying closer attention.

- I do a simple exercise in my class that illustrates this clearly. I send students to a familiar location, such as the local shopping center, and ask them to complete a “lab” in which they go to several stores and pay attention to all the things that are normally “invisible.” They take the time to notice the sounds. Smells, textures, and colors, as well as the organization of the merchandise and the way the staff interacts with the customers. They observe endless things they never saw when they previously zipped in and out of the same environment. They all come back with their eyes wide open, realizing that we all tend to walk through life with blinders on.

- And much of what I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on.

- In my course on creativity I focus a great deal on the value of recombining ideas in unusual ways. The more you practice this skill, the more natural it becomes.

- We do a simple exercise to illustrate this point. Teams are asked to come up with as many answers as possible to the following statement:

- Ideas are like_____

- Because____

- Therefore______

- Ideas are like babies because everyone thinks theirs is cute, therefore be objective when judging your own ideas.

- Ideas are like shoes because you need to break them in. therefore take time to evaluate new ideas.

- Ideas are like mirrors because they reflect the local environment, therefore consider changing contexts to get more diverse collections of ideas.

Chapter 8 Paint the Target around the arrow

- But the importance of writing thank you notes remains one of her most valuable lessons. Showing appreciation for the things others do for you has a profound effect on how you’re perceived.

- This serves as a reminder of the importance of every experience we have with others, whether they are friends, family. Co-workers, or service providers. In fact, some organizations actually capture information about how you treat them, and that influences how they treat you. For example, at some well known business schools, every interaction a candidate has with the school or its personnel is noted. If a candidate is rude to the receptionist, this is recorded in his or her file and comes into play when admissions decisions are made. This also happens at companies such as JetBlue. According to Bob Sutton’s. The No Asshole Rule, if you’re consistently rude to JetBlue’s staff, you will get blacklisted and find it strangely impossible to get a seat on their planes.

- Thinking about how you want to tell the story in the future is a great way to assess your response to dilemmas in general.

- Stan Christensen

- He also advises you to pick your negotiating approach based on the interests and style of the person with whom you’re negotiating, not on your own interests. Don’t walk into any negotiation with a clearly defined plan, but instead listen to what’s said by the other party and figure out what drives them. Doing so will help you craft a positive outcome for both sides.

- The idea is that you should pick the most talented person you can—the arrow—and then craft the job—the target—around what he or she does best.

- One of the biggest things that people do to get in their own way is to take on way too many responsibilities. This eventually leads to frustration all the way around.

- Life is a huge buffet of enticing platters of possibilities, but putting too much on your plate just leads to indigestion. Just like a real buffet, in life you can do it all, just not at the same time.

Chapter 9 WILL THIS BE ON THE EXAM?

- Being fabulous implies making the decision to go beyond what’s expected at all times.

- Bernie Roth, a Stanford mechanical engineering professor, does a provocative exercise at the d.school to highlight this point. He selects a student to come up to the front of the room says, “Try to take this empty water bottle out of my hand.” Bernie holds the bottle tightly and the student tries, and inevitably fails, to take it. Bernie then changes the phrasing slightly. Saying, “Take the water bottle from my hand.” The student then makes a bigger effort, usually without result. Prodding the student further, Bernie insists that the student take the bottle from him. Usually the student succeeds on the third attempt. The lesson? There’s a big difference between trying to do something and actually doing it. We often say we’re trying to do something—losing weight, getting more exercise, finding a job. But the truth is, we’re either doing it or not doing it. Trying to do it is a cop-out. You have to focus your intention to make something happen by giving at least 100 percent commitment. Anything less and you’re the only one to blame for failing to reach your goals.

- He then took the management team on a seven-day wilderness expedition, during which they had to rely on each other in the rawest sense. This made office issues seem mundane by comparison

- This exercise offers a strong reminder that in environments where there are limited resources, being driven to make yourself and others successful is often a much more productive strategy than being purely competitive. Those who do this are better able to leverage the skills and tools that others bring to the table, and to celebrate other people’s successes along with their own. This happens in sports as well as in business settings, which are both often thought to be purely competitive. environments. For example, in It’s Not about the Bike, Lance Armstrong provides details about how competitors in the Tour de France work together over the course of the race in order to make everyone successful. And many competitive companies. Including Yahoo! And Google, embrace “coopetition” by finding creative ways to work together, leveraging each business’s strengths.

Chapter 10 EXPERIMENTAL ARTIFACTS

- I have a confession to make—I easily could have titled all of the previous chapters “Give Yourself Permission.” By that I mean, give yourself permission to challenge assumptions, to look at the world with fresh eyes, to experiment, to fail, to plot your own course, and to test the limits of your abilities. In fact, that’s exactly what I wish I had known when I was twenty, and thirty, and forty—and what I need to constantly remind myself: at fifty It’s incredibly easy to get locked into traditional ways of thinking and to block out possible alternatives. For most of us, there are crowds of people standing on the sidelines, encouraging each of us to stay on the prescribed path, to color inside the lines, and to follow the same directions they followed. This is comforting to them and to you. It reinforces the choices they made and provides you with a recipe that’s easy to follow. But it can also be severely limiting.