Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think

Brian Wansink, Ph.D.

Introduction: The Science of Snacking

Everyone – every single one of us – eats how much we eat largely because of what’s around us. We overeat not because of hunger but because of family and friends, packages and plates, names and numbers, labels and lights, colors and candles, shapes and smells, distractions and distances, cupboards and containers. This list is almost as endless as it’s invisible.

Invisible?

Most of us are blissfully unaware of what influences how much we eat. This book focuses on dozens of studies involving thousands of people who – like most of us – believe that how much they eat is mainly determined by how hungry they are, how much they like the food, and what mood they’re in. We all think we’re too smart to be tricked by packages, lighting, or plates. We might acknowledge that others could be tricked, but not us. That is what makes mindless eating so dangerous. We are almost never aware that it is happening to us.

Consider the physics of French fries. The Argonne National Laboratory helped McDonald’s discover how to speed up the time it took to cook French fries. A team headed by physicist Tuncer Kuzay put sensors inside the frozen French fries to best determine how to deal with the steam that was created by melting ice crystals. They then designed special frying baskets that cut 30 to 40 seconds off the frying time for each batch.

Chapter 1: The Mindless Margin

We overeat because there are signals and cues around us that tell us to eat. It’s simply not in our nature to pause after every bite and contemplate whether we’re full. As we eat, we unknowingly – mindlessly – look for signals or cues that we’ve had enough. For instance, if there’s nothing remaining on the table, that’s a cue that it’s time to stop. If everyone else has left the table, turned off the lights, and we’re sitting alone in the dark, that’s another cue. For many of us, as long as there are still a few milk-soaked Froot Loops left in the bottom of the cereal bowl, there is still work to be done. It doesn’t matter if we’re full, and it doesn’t matter if we don’t even really like Froot Loops. We eat as if it is our mission to finish them.

Stale Popcorn and Frail Willpower

Weighing the buckets told us that the big-bucket group ate an average of 173 more calories of popcorn. That is roughly equivalent to 21 more dips into the bucket. Clearly the quality of food is not what led them to eat.

Even though some of them had just had lunch, people who were given the big buckets ate an average of 53 percent more than those given medium-size buckets. Give them a lot, and they eat a lot.

Does this mean we can avoid mindless eating simply by replacing large bowls with smaller bowls? That’s one piece of the puzzle, but there are a lot more cues that can be engineered out of our lives. As you will see, these hidden persuaders can even take the form of a tasty description on a menu or a classy name on a wine bottle. Simply thinking that a meal will taste good can lead you to eat more. You won’t even know it happened.

As Fine as North Dakota Wine

Exact same meals, exact same wine. Different labels, different reactions.

They didn’t (eat the same amount & enjoy it the same). They mindlessly ate. That is, once they were given a free glass of “California” wine, they said to themselves, “This is going to be good.” Once they concluded it was going to be good, their experience lined up to confirm their expectations. They no longer had to stop and think about whether the food and wine were really as good as they thought. They had already decided.

Of course, the same thing happened to the diners who were given the “North Dakota” wine. Once they saw the label, they set themselves up for disappointment. ;;There was no halo; there was a shadow. And not only was the wine bad, the entire meal fell short.

Even when we do pay close attentyion we are suggestible – and even when it comes to cold, hard numbers. Take the concept of anchoring. If you ask people if there are more or less than 50 calories in an apple, most will say more. When you ask them how many, the average person will say, “66.” If you had instead asked if there were more or less than 150 calories in an apple, mom st would say less. When you ask them how many, the average person would say, “114.” People unknowingly anchor or focus on the number they first hear and let that bias them.

A while back, I teamed up with two professor friends of mine – Steve Hoch and Bob Kent – to see if anchoring influences how much food we buy in grocery stores. We believed that grocery shoppers who saw numerical signs such as “Limit 12 Per Person” would buy much more than those who saw signs such as “No Limit Per Person.” To nail down the psychology behind this, we repeated this study in different forms, using different numbers, different promotions (like “2 for $2” versus “1 for $1”), and in different supermarkets and convenience stores. By the time we finished, we knew that almost any sign with a number promotion leads us to buy 30 to 100 percent more than we normally would.

The Dieter’s Dilemma

Now for our brains. If we consciously deny ourselves something again and again, we’re likely to end up craving it more and more.

We lovingly leave latchkey snacks on the table for our children (and ourselves). eWe use the nice, platter-size dinner plates that we can pile with food. We heat up a slice of apple pie.

But on most days we have very little idea whether we’ve eaten 50 calories too much or 50 calories too little. In fact, most of us wouldn’t know if we ate 200 or 300 calories more or less than the day before.

This is the mindless margin.

That is, the difference between 1,900 calories and 2,000 calories is one we cannot detect, nor can we detect the difference between 2,000 and 2,100 calories. But over the course of a year, this mindless margin would either cause us to lose ten pounds or to gain ten pounds. It takes 3,500 extra calories to equal one pound. It doesn’t matter if we eat these calories in one week or gradually over the entire year. They’ll add up to one pound.

The Mindless Margin

This is the danger of creeping calories. Just 10 extra calories a day – one stick of Doublemint gum or three small Jelly Belly beans – will make you a pound more portly one year from today. Only three jelly beans a day.

“Oh yeah,” she said, “and because I gave up caffeine, I also stopped drinking Coke.” She had been drinking about seix cans a week – far from a serious habit – but the 139 calories in each Coke translated into 12 pounds a year. She wasn’t even aware of why she’d lost weight. In her mind all she’d done was cut out caffeine.

In a classic article in Science, Drs. James O. Hill and John C. Peters suggested that cutting only 100 calories a day from our diets would prevent weight gain in more of the U.S. population.

Cutting our our favorite foods is a bad idea. Cutting down on how much of them we eat is mindlessly do-able.

How Much Will I Lose In A Year?

If you make a change, there’s an easy way to estimate how much weight you’ll lose in a year. You simply divide the calories by 10. That’s roughly the number of pounds you’ll lose if you’re otherwise in energy balance.

One less 270 calorie candy bar each day = 27 fewer pounds a year

One less 140 calorie soft drink each day = 14 fewer pounds a year

One less 420 calorie bagel or donut each day = 42 fewer pounds a year

The same thing works with burning calories: walking one extra mile a day is 100 calories and 10 pounds a year. Exercise is good, but for most people it’s a lot easier to give up a candy bar than walk 2.7 miles to a vending machine.

Reengineering Strategy #1: Think 20 Percent-More or Less

- Think 20 percent less. Dish out 20 percent less than you think you might want before you start to eat. You probably won’t miss in. In most of our studies, people can eat 20 percent less without noticing it. If they eat 30 percent less they realize it, but 20 percent is still under the radar screen.

- For fruits and vegetables, think 20 percent more. If you cut down on how much pasta you dish out by 20 percent, increase the veggies by 20 percent.

Chapter 2: The Forgotten Food

Five minutes after dinner, 31 percent of the people leaving an Italian restaurant couldn’t even remember how much bread they ate, and 12 percent of the bread eaters denied having eaten any bread at all.

Sometimes it even surprises us how predictable people are. If our guests had their tables continually bussed, they continually ate. Clean plate, clean table, get more, eat more. Their stomachs could not count, so the clear-table group kept eating until they thought they were full. They ate an average of seven chicken wings apiece.

The people at the bone-pile tables were less of a threat to the chicken population. After the Super Bowl was over, they had eaten an average of two fewer chicken wings per person – 28 percent less than those whose tables had been bussed.

The Prison Pounds Mystery

The food served in county jails is not typically awarded any Michelin stars. In fact, complaining about the food is one of the great inmate pastimes. This is why a sheriff at one Midwestern jail was puzzled when he noticed an odd trend: the inmates, with an average sentence of six months, were mysteriously gaining 20-25 “prison pounds” during the course of their “visit.” It wasn’t because the food was great. Nor did it seem to be because they hadn’t exercised or because they were lonely and bored. They generally had access to exercise facilities and to daily visitors.

In fact, upon release, no inmate blamed the food, the exercise machines, or the visitation hours for their weight gain. They blamed their jailhouse fat on the baggy orange jumpsuits they had to wear for six months. Because these orange coveralls were so loose-fitting, most of them didn’t realize they had progressively gained weight – about a pound a week – until they were released and had to try and squeeze back into their own clothes.

Eye It, Dish It, Eat It

What does seem to be the cause is that the faster we wolf down our food, the more we eat, because this combination of cues doesn’t get the chance to tell us we’re no longer hungry. Many research studies show that it takes up to 20 minutes for our body and brain to signal satiation, so that we realize we are full.

Think of a jogger. If she decides to jog on a treadmill until she’s tired, she constantly has to ask herself, “Am I tired yet, am I tired yet, am I tired yet?” But if she says, “I’m going to jog down to the school and back,” she doesn’t have to constantly monitor how tired she is. She sets the target, and jogs until she’s done.

The Bottomless Soup Bowl

People eating out of the normal soup bowls ate about 9 ounces of soup. This is just a little less than the size of a nondiluted Campbell’s soup can (10.5 ounces). They thought they had eaten about 123 calories’ worth of soup, but, in fact, they had eaten 155. People eating out of the bottomless soup bowls ate and ate and ate. Most were still eating when we stopped them, 20 minutes after they began. The typical person ate around 15 ounces, but others ate more than a quart – more than a quart. When one of these people was asked to comment on the soup, his reply was, “It’s pretty good, and it’s pretty filling.” Sure it is. He had eaten almost three times as much as the guy sitting next to him.

Surely diners realized that they ate more from the refillable bowl? Absolutely not. With a couple of exceptions, such as Mr. Quart Man, people didn’t comment about feeling full. Even though they ate 73 percent more, they rated themselves the same as the others – after all, they only had about half a bowl of soup. Or so they thought. When asked how many calories of soup they ate, the 127 calories they estimate was nearly the same as that estimated by those people eating from the normal bowls. In reality, they had eaten an average of 268 calories. This was 113 calories more than their tablemates with the normal bowls.

Not knowing when to stop turns Thanksgiving dinners, buffets, and dim sum restaurants into diet dangers. And what if we earnestly try to guesstimate how many calories we’re eating? Sorry, it still won’t help much.

Why French Women Don’t Get Fat

Why don’t French women get fat – even though they consume cheese, baguettes, wine, pastries, and pate? As Mireille Guiliano proposed in her bestselling book, it is because they know when to stop eating. Our own research suggests that they pay more attention to internal cues, such as whether they feel full, land less attention to the external clues (like the level of soup in a bowl) that can lead us to overeat.

To see if this was true, we had 282 Parisians and Chicagoans fill out questionnaires asking them how they decided it was time to stop eating a meal. Parisians reported that they usually stopped eating when they no longer felt hungry. Not our Chicagoans. They stopped when they ran out of a beverage, or when their plate was empty, or when the television show they were watching was over. Yet the heavier a person was – American or French – the more they relied on external cues to tell them when to stop eating and the less they relied on whether they felt full.

Chapter 3: Surveying the Tablescape

And yet the tablescape you were asked to visualize is filled with hidden persuaders. Each of the innocuous-looking items on the table – packages, dishes, glasses, and the variety of foods – can increase how much we eat by well over 20 percent. They can also be used to decrease how much we eat. Either way – up or down – the impact they have on us will be mindless.

King-Size Packages and the Power of Norms

Americans are often shocked when they check out the typical kitchen in Europe or Asia. Where is the island in the middle, where are the rows of cabinets, the pantry, the refrigerator the size of a Subaru? The micro-size of most foreign kitchens and refrigerators would render an American home nearly unsellable.

The danger of our huge American kitchens is that they give us lots of space to fill up with huge American packages. We can buy bigger boxes of pasta, restaurant-size jars of spaghetti sauce, and chunker packages of ground beef. Some of us even buy an extra refrigerator or deep freezer.

We’ve done dozens of similar studies with dozens of different foods. With spaghetti, for instance, we found that the people who were given the large package of pasta, sauce, and meat typically prepared 23 percent more – around 150 extra calories – than those given the medium packages.

Did they eat it all? Yes. We find over and over that if people serve themselves, they tend to eat most – 92 percent – of what they serve. For many of the breakfast, lunch, and dinner foods we have studied, the result is about the same – people eat 20 to 25 percent more on average from the larger packages. For snack foods, it’s even worse.

The results were dramatic. Those who were given a half-pound bag ate an average of 71 M&M’s. Those who were given the one-pound bag l;ate an average of 137 M&M’s, almost twice as many – 264 calories more. Sure, a person saves some money by buying the big bag, but if he decides to watch a hundred videos in the next year, it will also cost him nine pounds of extra weight.

The bottom line: We all consume more from big packages.

As all of our studies suggest, we can eat about 20 percent more or 20 percent less without really being aware of it. Because of this, we look for cues and signals that tell us how much to eat. One of these signals is the size of the package. When we bring a big package into our kitchen, we think it’s typical, normal, and appropriate to mix and to serve more than if the package were smaller.

Drinking Glass Illusions

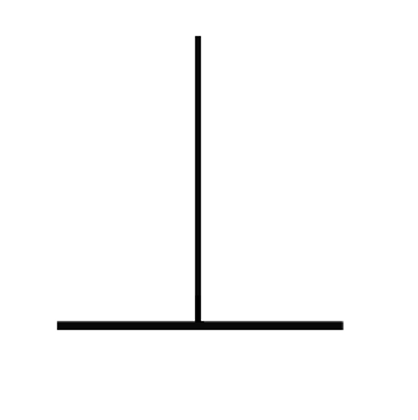

You may remember the Horizontal-Vertical illusion from a brain-teasers book you had as a kid. This common illusion looks like an upside-down capital “T.” The horizontal and vertical lines are exactly the same length, but virtually everyone thinks the vertical line is longer: 18 to 20 percent longer, on average.

The Horizontal-Vertical Illusion: Which Line is Longer?

Our brains have a basic tendency to overfocus on the height of objects at the expense of their width. Take the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.

The arch is America’s tallest man-made monument. It is also exactly the same height as width – 630 feet tall and 630 feet wide. Despite this, none of the 11,000 tourists who visit the arch on an average day says, “Wow… look how wide it is.” No way, we all stare at the height.

The campers who’d been given the tall, thin glasses poured about 5.5 ounces. But for those campers given the short, wide glasses, it was a different story. They poured an average of 9.6 ounces – 74 percent more than their tall-glass buddies. The real surprise: They estimated that they had poured only 7 ounces.

Even though they were older and wiser, they still got fatter if they used the short glasses. The people given a short, wide glass poured an average of 19 percent more juice or soft drink than those given the tall, thin glass.

What happened? Those who were given the tall, skinny glasses were almost exactly on target. They poured 1.6 ounces. Those who had been given the short, fat glasses were a different story. Even though they had poured drinks for over five years, and even though they always poured the same amount, they poured an average of 2.1 ounces: 37 percent more than their target. We even asked an additional 41 bartenders to “Please take your time when pouring.” They still overpoured. So much for experience.

After seeing that even expert pourers get fooled, most of us from the Lab replaced the short, wide juice glasses in our kitchens and kept the taller ones. One of our researchers even replaced his large, wide re-wine glasses with smaller, slender glasses intended for white wine.

Big Plates, Big Spoons, Big Servings

Essentially, we use background objects as a benchmark for estimating size. For instance, if we set a photo of a six-foot man standing next to a tricycle, we think he is taller than if he were shown next to a cement truck.

Now translate this to the tablescape. If you spoon four ounces of mashed potatoes onto a 12-inch plate, it will look like a lot less than if you had spooned it onto an 8-inch plate. Even if you intended to limit your portion size, the larger plate would likely influence you to serve more. And since we all tend to finish what we serve ourselves, we would probably end up eating it all.

None of that mattered. Those who were given the huge bowls dished out huge amounts. In fact, they dished about 31 percent more – 127 more calories’ worth of ice cream. It only makes things worse if you give them a big scoop. People with a large bowl and a three-ounce scoop dished out 57 percent more ice cream than those given a smaller bowl and smaller scoop.

Big dishes and big spoons are big trouble. As the size of our dishes increases, so does the amount we scoop onto them. They cause us to serve ourselves more because they make the food look so small.

The Super Bowl Intelligentsia

What did our size-bias experts do? The students who served themselves from the gallon bowls took 53 percent more Chex Mix than those serving themselves from half-gallon bowls. An hour later we cleared away their plates, which had identification codes on the bottom. Not only did those who served themselves from the large bowls take 53 percent more, they also ate more (59 percent more).

In the end, setting the table with the wrong dinner plates or serving bowls – the big ones – sets the stage for overeating. And there are heavyweight consequences, especially when you’re sitting in front of a wide variety of food.

The Temptation of Variety

Increasing the variety of a food increases how much everyone eats. To demonstrate this, Dr. Barbara Rolls’ team at Penn State has showed that if people are offered an assortment with three different flavors of yogurt, they’re likely to consume an average of 23 percent more than if offered only one flavor.

Sensory specific satiety also affects our taste buds. The first bit of anything is almost always the best. The second a little less, the third less again. At some point, we’re tired of the yogurt or cake. But if we add two more types of yogurt, or if we add ice cream to the cake, our taste buds are back to the races.

This is why we eat more when there is variety. It’s a simple idea, but it has a lot of implications. If you’re trying to control your weight, one obvious implication is not to eat every meal at the Kung Pao Garden’s 2,000-item buffet. You can also stop thinking that every meal should consist of four or five different foods. And what about the reception or party where you’re tempted with dozens of merciless morself? A smart strategy is never to have more than two items on your plate at any one time. You can go back if you’re still hungry, but the lack of variety slows you down, and you end up eating less.

The other half of the moviegoers were offered the same six flavors of jelly beans, but instead of being neatly organized by color, they were all mixed together. Who do you think took more, the person eating from the organized tray or the person eating from the disorganized tray? The grad students faced with the organized tray took about 12 jelly beans and headed off to enjoy the movie. But those people presented with the disorganized assortment took an average of 23 jelly beans, nearly twice as many. In both cases, the number and flavors of jelly beans are identical, yet mixing them up nearly doubles how many a person takes and eats.

Most people know that all M&M’s taste alike. The color is just added to the coating. There’s no way they should eat different amounts.

But they do. The person with 10 colors will eat 43 dmore M&M’s (99 versus 56) than his friend with 7 colors. He does so because he thinks there’s more variety, which increases how much he thinks he’ll like the M&M’s and how much he thinks is normal to eat.

Instead of having three really large bowls of chips, peanuts, and candy, these shrewd, cost-conscious hosts and hostesses might put the chips in four small bowls, the peanuts in four small bowls, and the candy in four small bowls. It makes people think there’s a lot more food – and a lot more variety. Exact same variety, but very different perceptions.

At which party is the average person likely to eat more – the 12-bowl party or the 3-bowl party? Even though the amount of food was the same, putting the food in 12 bowls increased how much people ate by 18 percent. When we asked our guests to rate the variety, sure enough, they gave higher scores to the party with 12 bowls.

Reengineering Strategy #3: Be Your Own Tablescaper

- Mini-size your boxes and bowls. The bigger the package you pour from – be it cereal boxes on the table or spaghetti in the kitchen – the more you will eat: 20 to 30 percent more for most foods. How can you get your supersized savings and still eat less? Repackage your jumbo box into smaller Ziploc bags or Tupperware containers, and serve it up in smaller dishes. The smaller the box, the less yl;ou make, and the less you eat. The smaller the serving dish, the less you take, and the less you eat.

- Become an illusionist. Six ounces of goulash on an 8-inch plate is a nice-size serving. Six ounces on a 12-inch plate make it look like an appetizer. Make visual illusions work for you. After you drop your platter-size dinner plates off at Goodwill, pick up a nice set of mid-size plates that you can be proud of. With glasses, think slender if you want to be slender. If you don’t fill your glass, you’ll tend to pour 30 percent more into a wide glass than into a tall, slender one. It’s easier to get rid of your wide glasses than to constantly remind yourself not to use them.

- Beware of the double danger of leftovers. The more side dishes and little bowls of leftovers you bring out of the refrigerator, the more you will eat. If you’re bringing out carrot sticks, this probably doesn’t matter – but are you? The second danger of leftovers? They signal that you made too much – and probably ate too much – of the original meal.

Chapter 4: The Hidden Persuaders Around Us

The “See-Food” Trap

Secretaries who had been given candies in clear desktop dishes were caught with their hand in the candy dish 71 percent more often (7.7 versus 4.6 times) as those given white dishes. Every day that dish was on their desk they ate 77 more calories.

Why does this happen? We eat more of these visible “see-foods” because we think about them more. Every time we see the candy jar we have to decide whether we want a Hershey’s Kiss; or whether we don’t. Every time we see it, we have to say no to something that is tasty and tempting. If we see that temptress of a candy jar every five minutes, it means needing to say no 12 times the first hour, 12 times the second hour, and so on. Eventually some of those no’s turn into yes’s. Usually in the form of, “Well, okay, just this once…”

Out of sight, out of mind. In sight, in mind.

Simply thinking of food can make you hungry.

When we hear, see, or smell something we associate with food, like a shiny foil-wrapped piece of milk chocolate. Even though we haven’t touched the chocolate, our pancreas may begin to secrete insulin, a chemical used to metabolize the upcoming sugar rush we’re planning. This insulin lowers our blood sugar level, which makes us feel hungry. While drooling has never hurt anyone, the more actively you salivate, the more likely you are to be impulsive and to overeat. Studies have even shown that the more we like the food the faster we’ll chew and swallow it.

Take two guys in side-by-side cubicles – Will and George – and two dozen stale donuts in the mail room. George saw the donuts when he first got to work and has been thinking about them all morning. Every five minutes he thinks of them, and every five minutes he says no. Eventually, however, the no’s are more difficult, so he gets up from h is desk to go get a donut. Will, on the other hand, doesn’t know the donuts are there, but he decides to go down and pick up his mail. Both arrive there at the same time. Who will eat more?

The more you think of something, the more of it you’ll eat.

The “Hide the See-Food” Diet

Make healthy foods easy to see, and less healthy foods hard to see.

I am invariably hungry when I come home at the end of the day. For the longest time, I would enter the house through a door that led me through the kitchen.

The solution? He changed his route and came in the front door instead of the back door.

The more hassle it is to eat, the less we eat.

Inconvenient foods that take a lot of effort to obtain and prepare seem to have an even greater influence on people who are obese.

By now you can predict what happened. The typical secretary ate about nine chocolates a day if they were sitting on her desk staring right at her. That’s about 225 extra calories a day. If she had to go to the effort of opening the desk drawer, she did so only six times a day. If she had to get up and walk six feet to get chocolate, she ate only four. In the same way that it’s not worth the effort for an Eskimo to locate and overeat mangos, it’s not always worth the effort for us to walk six feet for a chocolate. The basic principle is convenience.

However, something else might be going on here, as well. When we talked to the secretaries after the study, many of them mentioned having six feet between them and the candy gave them enough time to think twice whether they really wanted it.

Take the Chinese Buffet Chopstick Test

Eating with chopsticks can be a hassle. People eat slower and eat less per bite. This is why dieters are often told to eat with chopsticks. So who do you suppose is more likely to use a fork when eating in a Chinese resturaunt – a normal-weight person or an obese person?

We decided to find out. We observed 100 normal-weight diners and 1020 obese diners at Chinese buffets in California, Minnesota, and New York, and we noted whether they were eating with chopsticks or silverware.

Our of 33 people eating with chopsticks, 26 were normal weight and only 7 were obese.

Take the Chinese Buffet Chopstick test. Next time you find yourself at a Chinese restaurant, check out who’s eating with the chopsticks and who has a fork in their hand.

Cafeteria studies show this in a way that does not involve rats (we hope). In a cafeteria, as in our home, the convenience of food pretty much determines whether we will eat it or not. If people have to go to a separate lunch line to pay for candy and potato chips, they buy less. If the salad bar is farther away from the table, they will eat less salad. That’s not surprising.

The power of convenience even applies to milk and water. In the military, dehydration can have deadly results. Studies are continually being done to determine how to increase fluid intake. In one mess-hall study, soldiers drank almost twice as much water (81 percent more) when water pitchers were put on each dining table than when they were put on a side table. They drank 42 percent more milk when the milk machine was 12 feet away than when it was 25 feet away.

The Curse of the Warehouse Club

Now take those multi-pack containers. Having 48 packages of almost anything in your house affects consumption in two ways. The first is what we call “the salience principle” – these 48 packages tend to get in the way. You seem to see them everywhere, they fall out of the cupboard when you open it, they pile up on the counter, and they hide other foods. As a result of their salience, you end up eating them much more frequently than you normally would, particularly if the food is convenient to eat. There they are… every time you want a snack.

The second reason we eat these foods so fast brings us back to the idea of “norms.” Suppose you usually have two or three boxes of breakfast cereal in your cupboard. If you find yourself with only one box, it’s a signal you need to buy more. But if one day you find yourself with twelve boxes, you will tend to eat them up so the “right” number will be in your cupboard, and so you’ll have room for other foods.

Get a Better Deal from Your Wholesale Club

- Reseal packages. Using tape to close a bag of chips is more of a deterrent to an impulse splurge than an easy-to-open clip.

Reengineering Strategy #4: Make Overeating a Hassle, Not a Habit

- Leave serving dishes in the kitchen or on a sideboard. Like the secretaries who snatched candies and ate them before they realized it, we do the same thing with serving bowls that are right in front of us. Having them at least six feet away gives us a chance to ask if we’re really that hungry. Turn this around for salad and veggies. Make sure they’re firmly planted in the “pick me” spot in the middle of the table.

- “De-convenience” tempting foods. Take those temptresses down to a remote corner of the basement or put them in a hard-to-reach cupboard. Reseal packages and wrap the most tempting leftovers in aluminum foil and put them in the back of the refrigerator or freezer.

- Snack only at the table and on a clean plate.This makes it less convenient to serve, eat, and clean up after an impulsive snack.

Of course, a better idea yet is to not bring impulse foods in the house to begin with. Eat before you shop, use a list, and stick to the perimeter of the store. That’s where the fresh foods hang out.

Chapter 5: Mindless Eating Scripts

When we eat, we often follow eating scripts. We encounter some food situations so frequently that we develop automatic patterns or habitual behaviors to navigate them.

Family, Friends, and Fat

We forget whether we ate two bread rolls or three, or whether we had seconds or thirds of the pasta. We’re so involved with our friends or family, that the whole idea of monitoring what’s going into our mouths is strange. We know we ate, but we don’t know how much.

Rescripting Your Dinner

- Try to be the last person to start eating.

- Pace yourself with the slowest eater at the table.

- Avoid the “just one more helping” request (and temptation) by always leaving some food on your plate as if you’re still eating.

- Preregulate consumption by deciding how much to eat prior to the meal instead of during the meal.

On average, if you eat with one other person, you’ll eat about 35 percent more than you otherwise would. If you eat with a group of seven or more, you’ll eat nearly twice as much – 96 percent more – than you would if you were eating alone at the Thanksgiving card table in the other room.

Birds of a feather eat together. This may be one contributing reason why couples and families tend to be similar sizes. That is, some families are skinny and some families are not. If there’s a majority of overweight people in a family, the frequency, quantity, and time spent eating puts more pressure on a person who’s trying to lose weight. Weight can be inherited, but it can also be contagious.

All-You-Can-Eat Television

It’s about as close to an established fact as things get in the social sciences: People who watch a lot of TV are more likely to be overweight than people who don’t. The less TV people watch, the skinnier they are. It doesn’t matter if they’re 14 or 44. It doesn’t matter if they watch network TV, cable TV, the Food Network, or the NASCAR network. As TV viewing goes up, weight goes up, and there are good reasons why.

Slow Italian and Fast Chinese

Owners, waiters, diners, lend me your ears. With pleasant, slow, semi-familiar music playing in the restaurant, diners stuck around 11 minutes longer (56 minutes total) than did diners on the fast-music nights. While they did not spend more money on food, the average slow-music table spent over $30 on drinks, far more than the $21.62 spent by the fast-music group. What was the soft music worth? An extra 41 percent in drink revenues per table.

Even though most people were on their lunch break and needed to return to work, those in the relaxing atmosphere lingered and ate for 11 minutes longer than those in the main eating area.

Restaurant Rules: Enjoy More and Eat Less

- If the breadbasket is on the table, you’re going to eat bread. Either ask the waiter to take it away early or keep it on the other side of the table.

- Portion sizes are often ample – split an entree, have half packed to take home, or simply order two appetizers instead.

- While soft music and candlelight can improve your enjoyment of a meal, remember that they can make you eat more if you linger, and prompt you to give into the temptation of dessert or another drink.

- If you want a dessert, see if someone will share it with you. The best part of a desert is the first two bites.

- Establish a Pick-Two rule: appetizer, drink, dessert – pick any two.

Follow Your Nose

Successful marketing is about positive associations and memory, and smell is hardwired to memory. Cinnabon has this nailed. Cinnabon stores are positioned besides stores that don’t sell food, so there’s no smell competition. As a result, you can walk through the mall feeling perfectly fine, but once you catch that first whiff of Cinnabon goodness wafting through the air, you’re hooked.

Smell is big business. There are companies that exist solely because they can infuse (the word they oddly use is “impregnate”) odors into plastics. This is because odor can’t reliable be infused into food. Sometimes it doesn’t last; at other times it changes the shelf stability of the food itself. But if you infuse the odor into packaging, it’s a different story. Some day you might heat up your frozen microwavable apple pie and smell the rich apple pie aroma. Even if it’s the container that you’re smelling, you’re primed to enjoy that apple pie even before you put your fork in.

What we found was that smell made a big difference. Adding a nice cinnamon-and-raisin smell to our plain tasting oatmeal led people to eat more. Adding an inconsistent odor – macaroni and cheese – got them to eat notably less. Even though it didn’t change the taste of their food, the sensory confusion put a real damper on their appetite.

The power of smell-appetite connection has not been lost on the supermodel world. If a smell can help make you feel full or sated or satisfied, it can also be used to curb cravings until they pass. It’s not uncommon for supermodels to buy a candy bar, take a bite, chew it, and spit it out. Some even keep the wrapper, so they can smell it for a fix.

Check the Weather Forecast

dIn the middle of a cold January night, we need more energy to warm and maintain our core body temperature, so our body tells us to eat more, and it even speeds up our digestion so we’ll feel hungry sooner.

Reengineering Strategy #5: Create Distraction-Free Eating Scripts

- Rescript your diet danger zones. We all have various eating scripts for the five most common diet danger zones – dinners, snacks, parties, restaurants, desks/dashboards. (See Appendix B.) A common dinner script – particularly for men – involves eating second helpings of most foods until everyone at the table is finished or until the food is gone. If such a man wanted to rescript his dinner, he might try being the last one to start eating, pacing himself with his spouse, serving triple helpings of the healthy foods and single helpings of the meat and potatoes, or not including bread. Similarly, after- work snacking could be rescripted with a stick of gum rather than whatever is in the refrigerator.

- Distract yourself before you snack. Distractions are good news and bad news. They are good when they prevent us from starting to snack. They are bad when they prevent us from stopping. At home, you can make your snacking life less distracting a less alluring by eating in one room only, such as the dining room or kitchen.

- Serve yourself before you start. If you can’t distract yourself from a yummy snack, you can minimize the damage is does in a distracting situation (such as eating in front of the TV). To avoid “eating until it’s over,” dish yourself out a ration before you start. Eating straight from a box, bag, or serving bowl is the recipe for regret.

Chapter 6: The Name Game

Eating in the Dark

Then we turned out the lights in the lab.

And we did not give them strawberry yogurt. We gave them chocolate yogurt. It didn’t seem to matter very much. The mere suggestion that they were eating strawberry yogurt led 19 to 32 people to rate it has having a good strawberry taste. One even said that the strawberry yogurt was her favorite yogurt and this would be her new favorite brand. Soldiers, just like us, use all sorts of cues or signals to help taste food. One of these is our eyesight. If it doesn’t look like strawberry, it doesn’t taste like strawberry. But another important cue is the name of the food. If we can’t see the food, and someone tells us we’re going to taste strawberry, we taste strawberry, even if it’s really chocolate.

A rose may be a rose by any other name. But this isn’t true with food. Except in extreme cases, we taste what we think we will taste.

Menu Magic

Yet if these menu names and descriptions seem so ridiculous out of context, why are they so common?

They are common because they work. They work in two ways. First, they entice us to buy the food. Second, they lead us to expect it will taste good, which pretty much pre-programs our taste buds.

Consider two pieces of day-old chocolate cake. If one is named “chocolate cake,” and the other is named “Belgian Black Forest Double Chocolate Cake,” people will buy the second. That’s no surprise. What’s more interesting is that after trying it, people will rate it as tasting better than an identical piece of “plain old cake.” It doesn’t even matter that the Black Forest is not in Belgium.

Margin note: Kid Schools

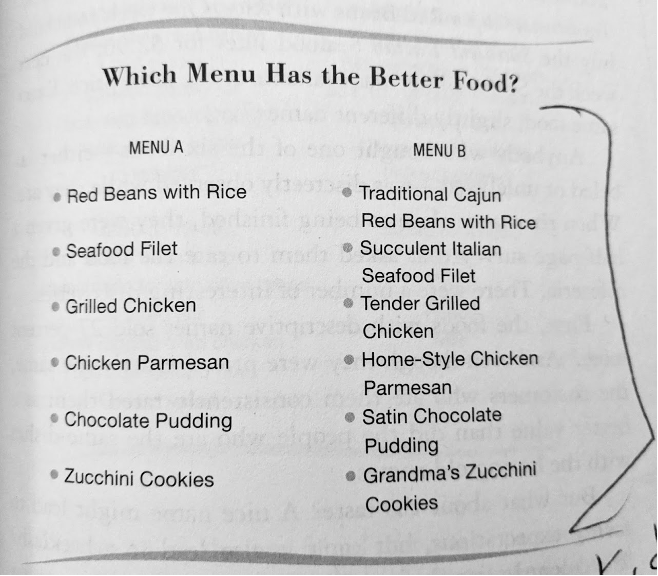

Back to the Bevier Cafeteria. Cafeteria food, like school hot lunches, has its share of image problems. This particular cafeteria was trying to enhance its image while also encouraging people to buy more of their vegetable side dishes and healthier foods. How could this be done? By changing the names of the foods.

We took six different foods – vegetables, main dishes, and low-fat desserts – and offered them on different days. Sometimes they had their boring, basic name and sometimes they had a slightly more descriptive name. Every day for six weeks we rotated these foods on and off the menu so no one would become suspicious. One day Red Beans and Rice would be offered, and two weeks later it would reappear as Traditional Cajun Red Beans with Rice. One week you could buy the Succulent Italian Seafood Filet for $2.90; the next week the Seafood Filet was available at the same price. Exact same food; slightly different names.

Anybody who bought one of the six foods – either labeled or unlabeled – was discreetly observed while they ate. When they were close to being finished, they were given a half-page survey that asked them to rate the food and the cafeteria. There were a number of interesting discoveries.

First, the foods with descriptive names sold 27 percent more. And even though they were priced exactly the same, the customers who ate them consistently rated them at a better value than did the people who ate the same dishes with the boring old names.

But what about the taste? A nice name might lead to raving expectations, abut can’t it also lead to a backlash? “Succulent Italian Seafood Filey… no way, this tastes more like a dry fishstick!” After all, truth be told, the food was nothing special.

Not so. The foods with descriptive names were rated as more appealing and tastier than the identical foods with the less attractive labels. Furthermore, when asked what they thought about the foods, the diners eating the descriptive foods tended to claim that they were “fantastic” or “great recipes.”

Margin note: Take to school board

Yet something else was found that was of particular interest to the cafeteria. The customers who ate the food with descriptive names had more favorable attitudes toward the cafeteria as a whole. Some commented that it was trendy and up-to-date. Others thought the chef was probably classically trained, perhaps in Europe. Again, the foods were exactly alike. The only difference was the addition of one or two descriptive words. These one or two words changed sales, tastses, and attitudes toward the restaurant.

Do Sweetbreads Taste Like Coffeecake?

Still other perceptions were based on non-soy-related events. A number of people mentioned that whenever they heard the word “soy,” they thought of a 1973 Charlton Heston movie – the guilty-pleasure classic Soylent Green. In this futuristic world, the only food source is a mysterious green substance called “soylent green.” In the closing moments of the movie, Charlton Heston discovers that the source of soylent green is reconstituted humans. He stretches his arms skyward, falls to his knees, and bellows, “Soylent green is peeeoople.”

Thirty years ago, almost none of us would’ve eaten something called an “unflavored bioactive dairy-based culture.” But if we stirred in some fruit, sugar, flavoring, innovation, and marketing, our tastes would change. In fact, a silky lemon yogurt sounds pretty good right now.

Reengineering Strategy #6: Create Expectations That Make You a Better Cook

- Tell them what’s for dinner. Suppose you’re asked, “What’s for dinner?” Any two words you say will make you a better cook as long as they are positive and descriptive. Simply adding words like “traditional,” “Cajun,” “succulent,” and “homemade” caused people in our cafeteria study to think the food tasted better and that the cook was European-trained. Big dinner party planned? The two-word technique will probably be the biggest five-minute fix to your cooking ability that you can make. What words should you use? Download a couple of restaurant menus while your oven is preheating.

- Fix the atmosphere when you fix the food. Spending your last 15 minutes of prep on atmospheric details will probably give you more bang than if you spend them on the food. Think soft – soft lights, soft music, soft colors. Think nice – nice plates, nice tablecloth, nice glasses. Even pizza tastes better by candlelight. Just remember to take it out of the box before you put it in the oven.

Chapter 7: In the Mood for Comfort Food

Comfort Foods and Comfort Moods

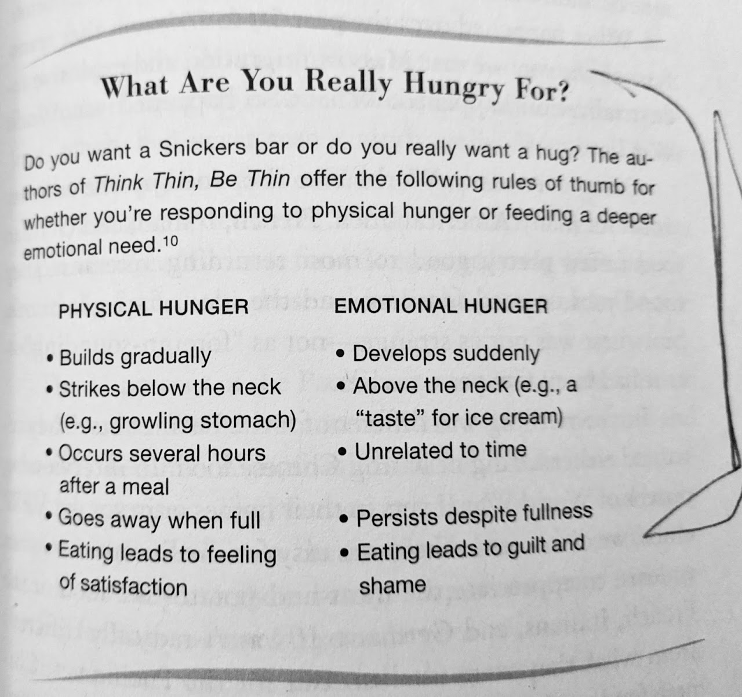

Moods, however, do seem to influence what we choose to eat. People in happy moods tended to prefer healthier foods.

If we want to repair a bad mood, a quick (but temporary) way to do it might be to eat something indulgent that tastes great and gives us that bump of euphoria. It’s different when we’re in a good mood. If we want to maintain or extend that happy feeling, we can do so by eating a food that scores higher on nutrition and lower on guilt.

Do You Save the Best for Last?

At dinnertime do you eat your favorite foods first or do you tend to save the best for last? The world is divided in half on this issue. We discovered why, but quite accidentally.

When we looked again at the questionnaires they had completed, we discovered that people who ate the best one first often shared one of two characteristics: they either grew up as a youngest child or came from large families.

The people most likely to save the best for last, on the other hand, had grown up as an only child or as the oldest. They could afford to save their favorite foods as a reward knowing it would still be waiting for them at the end of the meal. It’s different for children in big families, particularly if they’re not the oldest.

In the end, our childhood eating habits can follow us for years. If a child becomes conditioned to eat their favorite foods first, they might develop the long-term eating habit of filling up on the high-calorie goodies at the expense of the healthier salads, fruits, and vegetables. That is a recipe for obesity.

Reengineering Strategy #7: Make Comfort Foods More Comforting

Just like the Chinese graduate student who developed American comfort-food favorites in her 20s, we can rewire our comfort foods. The key is to start pairing healthier foods with positive events. Instead of celebrating a personal victory or defeat with the “death by chocolate” ice cream sundae, try a smaller bowl of ice cream with fresh strawberries. It’s not a big sacrifice, and before long it will start to inch up your “favorites” list.

Chapter 8: Nutritional Gatekeepers

If you struggle with your own food heritage, here is where you get your second chance – as a nutritional gatekeeper.

The biggest food influence in our life is the nutritional gatekeeper. This is the person in our home who does most of the food shopping and meal preparation.

The Nutritional Gatekeeper and the Good Cook Next Door

In most households, decisions about what to eat for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks are determined by what foods the grocery shopper – the nutritional gatekeeper – brings into the house. Although they don’t always realize it, gatekeepers powerfully shape what food gets eaten both inside and outside the home.

Suppose a teenager wants to eat Pop-Tarts, but there aren’t any in the cupboard? The gatekeeper has de facto decided they won’t be on the menu. This poor Pop-Tart hungry teenager either has to make a special trip to the grocery store, or pressure Mom or Dad to put them at the top of the next shopping list.

They estimated that the gatekeeper controlled 72 percent of the food decisions of their children and spouse.

; All of these cooks – except one – appeared to help their families eat healthier. They did this largely through the wide variety of food they served. A varied menu makes eating more pleasurable and can lead family members to expand their tastes beyond the standard fatty, salty, sweet foods for which we have a natural hankering.

Which good cook seemed to have the least positive impact on adult eating habits? Interestingly enough, it was the most common one – the giving cook. Although giving cooks put the stamp of variety on their meals, it was mostly in the form of high-carb entrees, baked goodies, and desserts.

Food Inheritance – Like Mother, Like Daughter

Escalona’s accidental discovery has aged well. Watching someone grimace when eating scares elementary children away from an otherwise tasty food. Smiles and friendliness work in reverse – you can attract more children to new foods with honey than with vinegar. When a friendly adult repeatedly gave children either canned unsweetened pineapple or cashews, they quickly learned to like the new food more than when it was given to them by a less friendly adult.

Is it Baby Fat or Real Fat?

The answer partly depends on the parents. A study of 854 Washington State children under

three years old showed that a child is nearly three times as likelyi to grow up obese if one of his

parents is obese. If you’re overweight, your child has a 65-75 percent chance l;of growing up to

be overweight.

So, is that little paunch on your fourth grader baby fat?

Not if you’re sporting the same paunch.

Margin note: me be healthy (?) (illegible, p172)

Food Conditioning and the Popeye Project

My Lab tried to leverage this with a vacation Bible School group a short time ago. The children could choose what they wanted from a lunch buffet, but each day we would rename foods to give them better associations. For instance, when we renamed peas “power peas,” the number of children taking them nearly doubled. The most embarrassing poetic license we took was with a V8-like vegetable juice. We ran out of it on the days we renamed it “Rainforest Smoothie.”

Setting Serving Size Habits for Life

Almost exactly the same thing happens to adults. We let the size of a serving influence how much we eat.

What is a healthy-size snack? Children tend to think that a serving size is open-ended and up for negotiation – it is pretty much whatever food is available and whatever they can weasel out of their parents. If a candy bar comes in a two-ounce package, two ounces must be the correct serving.

If you buy in bulk to save money, you can use the Baggie trick. Remember that none of us really seem to know the amount of a “correct” serving size. We typically look at whatever is wrapped or served and we assume that must be one serving. We can use this notion with our children by giving them their snacks not on a plate, but by putting them in a Biggie (or even in a small Tupperware container).

Like adults, children use external cues to determine whether they want more to eat. If they think more is available, they can easily think they’re still hungry.

Reengineering Strategy #8: Crown Yourself as the Official Gatekeeper

For better or for worse, the nutritional gatekeeper controls around 72 percent of what your family eats. Children eat what tastes good and what’s convenient and what portion size they see as appropriate. You can use this to help create positive lifetime food patterns.

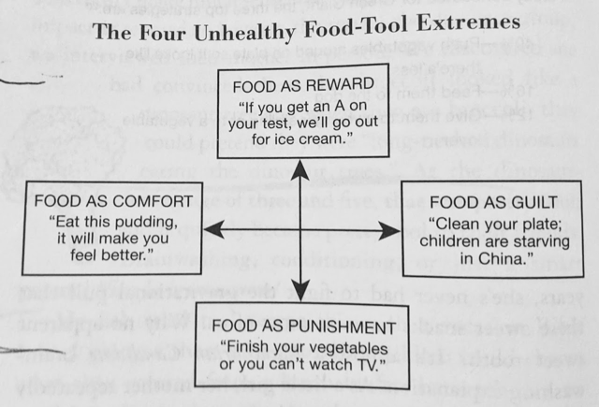

- Be a good marketer. Foods should be neither a punishment nor a reward. Healthy foods can, however, be fresh, crunchy, refreshing, and make you feel strong, smart, and maybe even “goiter-free.” (They might even be what long-necked dinosaurs ate.) Be convincing.

- Offer variety. Some of our early findings suggest that the more foods you expose your child to, the more nutritionally well-rounded he or she will become. Trying new recipes, new ingredients, ethnic foods, and different types of restaurants will all help mix it up and break the junk-food habit.

- Use the Half-Plate Rule. Around the house, the Half-Plate Rule can lead to more-balanced meals, and it can give your children the basic pattern for a healthy meal. Is steak and potatoes a balanced meal? No, it’s only half of the plate – you still need a vegetable or salad for the other half.

- Make serving sizes official. Provide “official” servings by giving your children their snacks in sealed Baggies, in Tupperware, or in Saran Wrap. Don’t let them see extra snacks. We found that any extra snacks on the counter increase the amount they see as a serving size. Clear off the counter at snack time.

Chapter 9: Fast-Food Fever

The “10-20” Rule and the Ice Water Diet

No big deal? If you drink the recommended eight 8-ounce glasses of water a day, and if you fill those 64 ounces with ice, you’ll burn an extra 70 calories a day. That’s approaching the mindless margin.

De-Marketing Obesity and De-Supersizing

Recent surveys of all foods ordered in restaurants show that burgers, French fries, pizza, and Mexican food comprise almost 50 percent of all food purchases. sWe order these foods five times more frequently than we order vegetables or side salads. Burger King offers a side salad that costs less than medium fries. But as my local Burger King manager told me, the fries win out 30 to 1. It’s the burgers and fries that keep people coming back.

- Think Extra-Small and Extra-Large.

But while some of us want supersized values, others want smaller packages. We call these the “Portion Prone Segment.” For instance, we found that half of the loyal users of one popular snack food said they would pay 15 percent more for a new package that helped them better control how much they ate.

- Create Packages with Pause Points.

Remember when we moved the candy dish six feet away from the secretaries and they ate half as many?

Stopping points can take other forms. We showed this in one of our Lab’s Red Chip studies. We took cans of Pringles (potato chips in a tube) and dyed every seventh chip red; in other cans, we dyed every fourteenth chip red; a last group of cans was left plain – no red chips. We then set up a video and invited people in to enjoy some Pringles. Those who ate from the cans where every seventh chip was red ate an average of 10. Those who ate from the cans where every fourteenth chip was red ate an average of 15 chips. Those with no red chips at 23. Having something, almost anything, to interrupt our eating gives us the chance to decide if we want to continue.

21st-Century Marketing

I believe the 21st century will be the Century of Behavior Change. Medicine is still making fundamental discoveries that can fight disease, but changing everyday, long-term behavior is the key to adding years and quality to our lives.

Chapter 10: Mindlessly Eating Better

Here are two more techniques for putting these principles to work: food trade-offs and food policies.

Food Trade-Offs – Food trade-offs state, “I can eat x if I do y.” For example, I can eat dessert if I’ve worked out; I can have chips if I don’t have a morning snack; I can have movie popcorn if I have only a salad for dinner; I can have a second soft drink if I use the stairs all day.

Food trade-offs are great because we don’t have to deny ourselves a food we love. We just have to make a small concession in the name of good health. Food trade-offs also put us back in charge of our food decisions by raising the “price we pay” for overeating.

Food Policies – The low-carb diet was initially successful because people didn’t have to make repeated decisions in the face of temptation. Many summarized the diet in one sentence: “Eat meat and vegetables, but nothing else.” This was a food policy. No need for “just this once” decision making, it was a personal rule. No exceptions.d

Food policies are great because you can personalize them to your situation. They come in many different forms: serve myself 20 percent less than I usually would; no second helpings of any styarch; never eat at my desk; only eat snacks that don’t come in wrappers; no bagels on weekdays; only half-size desserts. Food policies don’t involve any trade-offs, they just eliminate one or two habits that have mindlessly encroached on our lifestyle. We don’t have to commit to big sacrifices, we only have to pick up the habits we can easily forgo.

The Power of Three

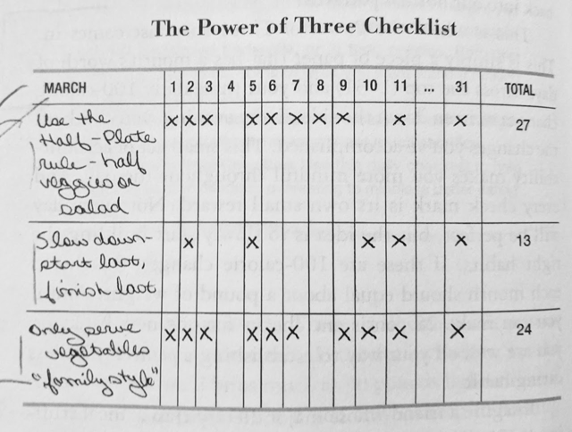

What three 100-calorie changes in your daily food routine would be easiest for you to turn into mindlessly positive eating habits?

Three small changes is reasonable. If we make three small, 100-calorie changes, by the end of the year we’ll be as much as 30 pounds lighter than if we didn’t make them.

This is where the Power of Three checklist comes in. This is simply a piece of paper that has a month’s worth of days across the top (1-31) ;and your three daily 100-calorie changes written down the side.

Appendix B

Defusing Your Diet Danger Zones

#1 The Meal Stuffer

Stuffers eat primarily during mealtimes, but then they eat to excess, cleaning everything on their plate. They often eat so quickly that they’re uncomfortably full after they finish. Meal stuffers consider themselves to have “healthy appetites.” They often take second helpings at home.

#2 The Snack Grazer

Grazers search for whatever food is available, typically about three times a day. eWhile they love the 4 C’s, convenience is usually more important to them than taste. They seldom pass up a candy dish. For these people, snacking can be a nervous habit, something that gives them an excuse to get up and walk around, or something they can do with their hands while watching TV or reading. They might be hungry when they snack, but it’s almost done more out of habit than hunger.

#3 The Party Binger

Parties – buffets, receptions, tailgates, and happy hours – these are high-distraction environments where the food is the backdrop for either business or fun, and it’s easy to lose track of how much they’ve eaten or drunk. Party bingers are often professionals who frequently wine and dine, or single, stay-out-late young people.

#4 The Restaurant Indulger

While many of us eat lunch away from home, the restaurant indulger also eats dinner out at least three days a week. Like party bingers, restaurant indulgers are often on an expense account. They may also be affluent gourmets or DINKs (double income, no kids) in their thirty-something years.

#5 The Desktop Diner (or Dashboard Diner)

Both speed-eat while multi-tasking at their desk or in their car. Desktop diners eat at the desk partly to save time, but more often to save the hassle of getting a real lunch. It’s not that they’re overly busy – they’re undermotivated. If the right person were to stop by to ask them to lunch, they’d probably go. But more often, they snack out of the vending machine or grab a donut from the mail room.

- For Meal Stuffers… Design a different Dinner.

Ever since he and his wife married 22 years ago, Peter has pretty much been the cook for the house. He loves making food, he loves gardening, and he loves to eat dinner… a little too much. Although his wife has been able to stay trim over the years, Peter and his two teenage daughters both have found that their weight has steadily grown. for a while, Peter attributed his increasing weight to turning 50 and to his ”slowing metabolism,” and he justified the weight gain of his girls as “growth spurts.” but even though all three of them are above average height, they’re getting bulky.

The notion of a diet or even watching what he ate seemed a bit too feminine to Peter, and he didn’t want to sacrifice much to get things back on track. A half-hearted attempt at an exercise program lasted about 5 days. If something was going to work for him, it needed to be easy and convenient. It couldn’t be seen as a diet. The dinner needed to be tasty – not steamed vegetables and four ounces of boiled fish.

Peter didn’t want to make his daughters self-conscious about their weight and about dieting. He loves that his wife never talks about her weight.

The meall stuffer needs to design a different dinner. Meal stuffing is a common problem with men, and it’s worse at the evening meal. Choosing three of the following changes is something Peter could easily do. After the first month, he wouldn’t even notice the difference – except in his weight.

- Preplate the high calorie foods in the kitchen and leave the leftovers there. Do not serve what some call “fat-family style,” unless it’s veggies and salad.

- Keep dinner classy by using nice dishes, but you smaller plates and taller glasses.

- Manage the pace. Slow down, so appetites can catch up with what’s been eating. Slow music can help.

- Avoid having too many foods on the table. The more variety there is, the more people will eat.

- Get into the habit of leaving something on the plate.

- Eat fruit for dessert instead of more indulgent choices.

- Adopt the Half-Plate Rule. Half the plate is filled with vegetables and the other half is protein and starch.

- For Snack Grazers… Avoid Snack Traps

- Think “back. “ For all those foods that aren’t good for you, think “Back.” put them in the back of the cupboard, in the back of the refrigerator, or in the back of the freezer. Keep these tempting goodies wrapped in aluminum foil.

- The only food that should be out on the counter are the healthy foods. Substitute a fruit dish for your cookie jar.

- Never eat directly from a package. Always portion food out into a dish so you must face exactly how much you’ll eat.

- For Party Bingers… Party Less Hearty.

- Stay more than an arm’s length away from the buffet tables and snack bowls.

- Put only two items on your plate during any given trip to the table.

- Use the volume approach to make yourself feel full. Chow down on the big healthy stuff (like broccoli and carrots) and then see if you have room for the rest.

- As you enter the room, tell yourself you’re there first to conduct business and secondarily to eat. Be aware that tension or nervousness maybe prompting you to refill your plate or your glass. The fact that Paperthis is not comfort food – you’re there for business, not pleasure – may strengthen your resolve to eat less or lighter food.

- if you plan to attend a cocktail party or a buffet-style dinner, arrive late or leave early. If you arrive late, most of the good stuff will be gone by the time you show up. Leave early and you’ll make it easier to avoid a second or third helping of dessert.

- For Restaurant Indulgers… Develop Restaurant Rules.

- Use the Rule of Two: limit yourself to two of the following: an appetizer, a drink, or a dessert. Pick any two.

- If the Bread Basket is on the table, you are going to eat bread. Either ask the waiter to forget it or to take it away early. You can also keep passing it so it stays on the other side of the table.

- For Desktop and Dashboard Diners… Change Gears.

- Brown-bag it. Even if you only do this a couple of times a week, you’re ahead of the game because you’re in more control of your food choices.

- Stop your desk or lunch room refrigerator with yogurt and pop-top cans of tuna fish. Protein can take the edge off a snack attack.

- Turn off the computer or pull the car over while you eat. If you focus on what you’re eating, you might even discover that you don’t really like vending machine or convenience store food.

- Use food policies and food trade-offs. For example, the first thing you eat at work is fruit; eating an indulgent snack means taking a walk during your break.

- Chew gum to prevent eating from boredom or stress.

- Replace every other soft drink with water. Offices tend to be dry. We often think we’re hungry when instead we’re simply thirsty. Fill up your water bottle and number of times each day.

Paperback Postscript: Frequently Asked Questions

You show how fast-food restaurants, buffets, and warehouse clubs can make people overeat, but you’re not against them. What’s the solution?

As we replay our video tapes of these buffet resistors, we’re pinpointing more and more behaviors that make them different. Here are a couple of early findings. First, the thinner the person, the more likely they were to “scout” out the entire buffet rather than digging in at the first table they came to. Before even picking up their plate, many of them walked around as if trying to see what they wanted most and what would be most “worth” the calories.

Second, when they did pick up their plate, they focused first on salads and low calorie starters – not on egg rolls and sugar buns. They certainly didn’t deny or starve themselves, but they weren’t vexed by a sense of urgency to eat their money’s worth of food in the first 15 minutes. They simply seemed to take their time and enjoy each course.

What should school lunch programs do to help our kids eat better?

Take apples, for instance. Here’s a change we made in one lunchroom in less than 10 minutes. When we used signs to say what kind of apples were being served (McIntosh or Red Delicious), apple sales increased by 16 percent. When we took five more minutes and move these apples and their banana compatriots in two baskets by the cash register, sales increased by 22 percent. For 15 minutes of effort, that’s a nice healthy return on investment.

Even if this finding holds up in further studies, we need to keep school lunches in perspective. Each week, school lunches makeup only 5 out of 21 of a child’s meals. This is far below what it takes to make a child fat. A much bigger concern is what happens during the other 16 meals (plus snacks) a child eat each week. That’s where the Nutritional Gatekeeper comes in.

Do you have any research on mindless drinking?

But – for men – If you do not want to keep track of how many beers you’ve had at the next barbecue or poker party, keep the bottle caps in your pants pocket. Every time your hand goes into your pocket you have an unbiased beer counter.

What’s the National Mindless Eating Challenge?

Whatever you want to accomplish, the Cornell Food and Brand Lab and I would like to give you our support. This is the purpose of our Web-Based National Mindless Eating Challenge (go to www.MindlessEating.org).

When you join the challenge, we will ask you questions about yourself, your goals, and your lifestyle. Based on your answers, we will then suggest the small changes to your home or office environment, or to your behavior, that are statistically most relevant to a person in your situation.