TINY HABITS + The Small Changes That Change Everything

BJ Fogg, PhD

INTRODUCTION: Change Can Be Easy (and Fun)

- Stop judging yourself.

- Take your aspirations and break them down into tiny behaviors.

- Embrace mistakes as discoveries and use them to move forward.

Behavior Design

Margin Note: Name

Behavior Design!

turned out to be wildly successful, like doing two push-ups every time I pee.

TINY CAN START NOW

TINY CAN GROW BIG

When Amy found the Tiny Habits method, she discovered that the best way to eat a monstrous whale — as little Melinda Mae did in Shel Silverstein’s poem — was to take one bite at a time. Amy ditched go big or go home and decided to go tiny. Every morning after dropping her daughter off at kindergarten, she pulled over on the side of the road and wrote one to-do on a sticky note. Just one. Each one was something she could accomplish right away: send out one sales e-mail, schedule a project meeting, draft a quick introduction to a patient guide. The simple act of focusing her energy on writing down one task led to a chain reaction that propelled her entire day and eventually led to the successful launch of her company. The feeling of success stuck with her as she drove home with her Post-it fluttering on the dashboard. And when she pulled into her driveway and grabbed the bright-pink sticky note, she took it inside to achieve a quick success.

TINY IS TRANSFORMATIVE

With the Tiny Habits method, you celebrate successes no matter how small they are. This is how we take advantage of our neurochemistry and quickly turn deliberate actions into automatic habits. Feeling successful helps us wire in new habits, and it motivates us to do more.

Step 1: Write this phrase on a small piece of paper: I change best by feeling good, not by feeling bad.

Step 2: Tape the paper to your bathroom mirror or anywhere you will frequently see it.

Step 3: Read the phrase often.

Step 4: Notice how this insight works in your life (and for the people around you).

CHAPTER 1: THE ELEMENTS OF BEHAVIOR

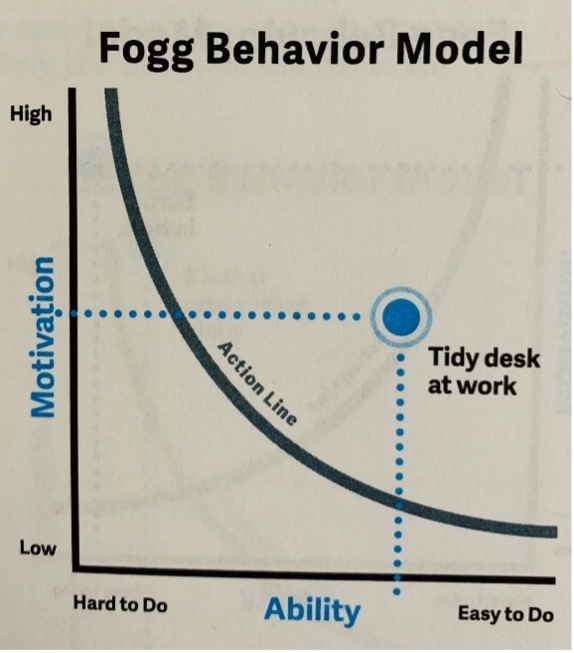

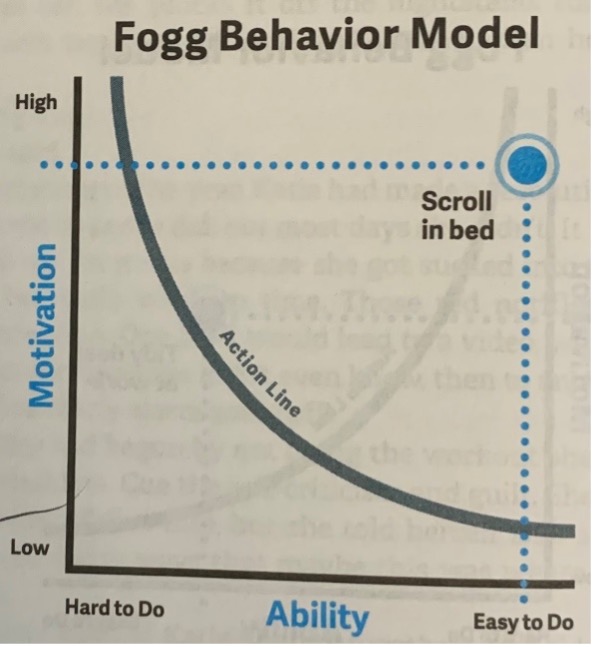

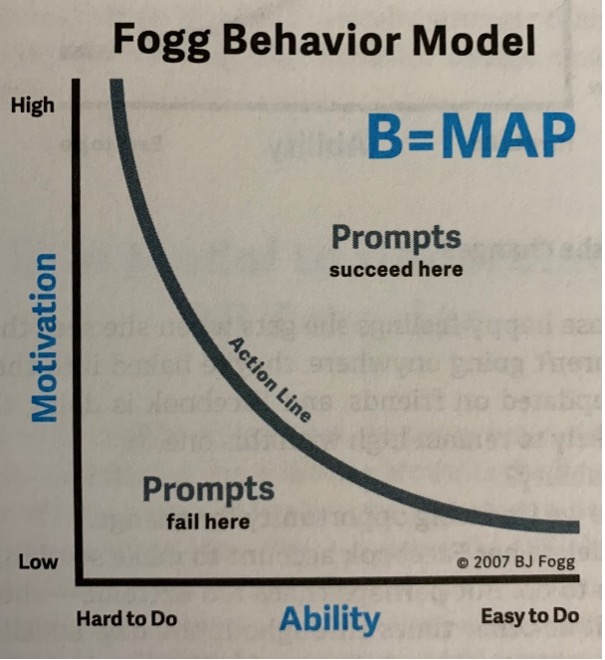

A behavior happens when the three elements of MAP — Motivation, Ability, and Prompt — come together at the same moment. Motivation is your desire to do the behavior. Ability is your capacity to do the behavior. And prompt is your cue to do the behavior.

When a behavior is prompted above the Action Line, it happens.

- The more motivated you are to do a behavior, the more likely you are to do the behavior.

- The harder a behavior is to do, the less likely you are to do it

Here’s a related insight that might begin to transform your life (it transformed mine): The easier a behavior is to do, the more likely the behavior will become habit.

This applies to habits we consider “good” and “bad”. It doesn’t matter. Behavior is behavior. It all works the same way.

- Motivation and ability work together like teammates

You need to have both motivation and ability for behavior to land above the Action Line, but motivation and ability can work together like teammates. If one is weak, the other needs to be strong to get you above the curve. In other words: The amount you have of one affects the amount you need of the other. Understanding the relationship of motivation and ability opens the door to new ways of analyzing and designing behaviors. If you have only a little bit of one, then you need more of the other

- No behavior happens without a prompt

If you don’t have a prompt, your levels of motivation and ability don’t matter. Either you are prompted to act or you’re not. No prompt, no behavior. Simple yet powerful.

A year or so ago I went to the South by Southwest conference in Austin, Texas. I walked into my hotel room and threw my bag on the bed. When I scanned the room, I saw something on the bureau.

“Oh nooooo,” I said out loud to absolutely no one.

There was an overflowing basket of goodies. Pringles. Blue chips. A giant lollipop. A granola bar. Peanuts. I try to eat healthy foods, but salty snacks are delicious. I knew the goodie bin would be a problem for me at the end of every long day. It would serve as a prompt: Eat me! I knew that if the basket sat there I would eventually cave. The blue chips would be the first to go. Then I would eat those peanuts. So I asked myself what I had to do to stop this behavior from happening. Could I demotivate myself? No way, I love salty snacks. Can I make it harder to do? Maybe. I could ask the front desk to raise the price of the snacks or remove them from the room. But that might be slightly awkward. So what I did was remove the prompt. I put the beautiful basket of temptations on the lower shelf in the TV cabinet and shut the door. I knew the basket was still in the room, but the treats were no longer screaming EAT ME at full volume. By the next morning, I had forgotten about those salty snacks. I’m happy to report that I survived three days in Austin without opening the cabin again.

Notice that my one-time action disrupted the behavior by removing the prompt. If that hadn’t worked, there were other dials I could have adjusted — but prompts are the low-hanging fruit of Behavior Design.

Three Steps for Troubleshooting a Behavior

We often want to do a behavior—or want someone else to do a behavior—and are met with little or no success. For those situations, I have good news: Behavior Design gives us a specific set of steps for troubleshooting this common problem. And it’s not what you’d expect. Let’s say you want your employees to show up to your weekly team meeting on time, but they consistently arrive a few minutes late. Many managers would get upset, impose a penalty, or shoot dirty looks at the people arriving late. All those are attempts to use motivation to get the behavior of arriving on time to happen. And all of those are mistakes. You don’t start with motivation when you troubleshoot.

You follow these steps instead. Try each step in order. If you don’t get results, move to the next step.

- Check to see if there’s a prompt to do the behavior.

- See if the person has the ability to do the behavior.

- See if the person is motivated to do the behavior.

As you know, this is not a good situation.

Now let’s rewind the story and imagine that you know how to troubleshoot. You don’t get upset when your daughter arrives home without the poster board on the first day. You go into troubleshooting mode: “Did you have anything to remind you to get the poster board?”

“No. I just thought I’d remember. But I forgot.”

So you design a prompt for the next day by asking, “What do you think would be a good reminder for you tomorrow?”

And she says that she is putting a to-do note on her phone.

Guess what? She hands you the poster board with a smile the next day.

When you apply this troubleshooting method to your own behavior, you’ll find that it stops you from blaming yourself. Let’s say you don’t meditate in the mornings as you hoped. Instead of blaming yourself for a lack of willpower or motivation, walk yourself through the steps: Did you have something to prompt you? What is making this hard to do? In many cases you’ll find your lack of doing a behavior is not a motivation issue at all. You can solve the behavior by finding a good prompt or by making the behavior easier to do.

CHAPTER 2: MOTIVATION—FOCUS ON MATCHING

- MOTIVATION IS COMPLEX

In my own work, I focus on three sources of motivation: yourself (what you already want), a benefit or punishment you would receive by doing the action (the carrot and stick), and your context (e.g., all your friends are doing it). To help you visualize this, I created a little guy called the PAC Person. You’ll see him pop up again and again — it turns out that Person, Action, and Context are fundamental for understanding human behavior.

OUTSMARTING MOTIVATION

Here’s an easy way to differentiate behaviors from aspirations and outcomes: A behavior is something you can do right now or at another specific point in time. You can turn off your phone. You can eat a carrot. You can open a textbook and read five pages. These are actions that you can do at any given moment. In contrast, you can’t achieve an aspiration or outcome at any given moment. You cannot suddenly get better sleep. You cannot lose twelve pounds at dinner tonight. You can only achieve aspirations and outcomes overtime if you execute the right specific behaviors.

I once worked with a major bank on a savings initiative. The objective was to encourage customers to have an emergency fund of five hundred dollars. The bank’s web pages had articles, experts, and data that made it clear that if you didn’t have the money for emergencies then you would get into financial trouble when you got a flat tire or clogged toilet that required a plumber.

“So what behavior are you asking your customer to do?” I asked.

“Save five hundred dollars for emergencies,” the project leader said.

To this group of highly educated, intelligent, and wonderful people, that seemed pretty specific. But notice that they were talking about an outcome, not a behavior.

I wanted to make this point, so I challenged the team in a playful way: “Each of you, save five hundred dollars right now.”

They laughed. And they got my point.

Then we went to work. I focused our session on finding specific behaviors their customers could do in order to create an emergency fund, and these are a few of the ones that we came up with.

- Call your cable company and scale back your service to the lowest level

- Empty your pocket change into an emergency-fund jar every evening

STEP 1: GET CLEAR ON YOUR ASPIRATIONS

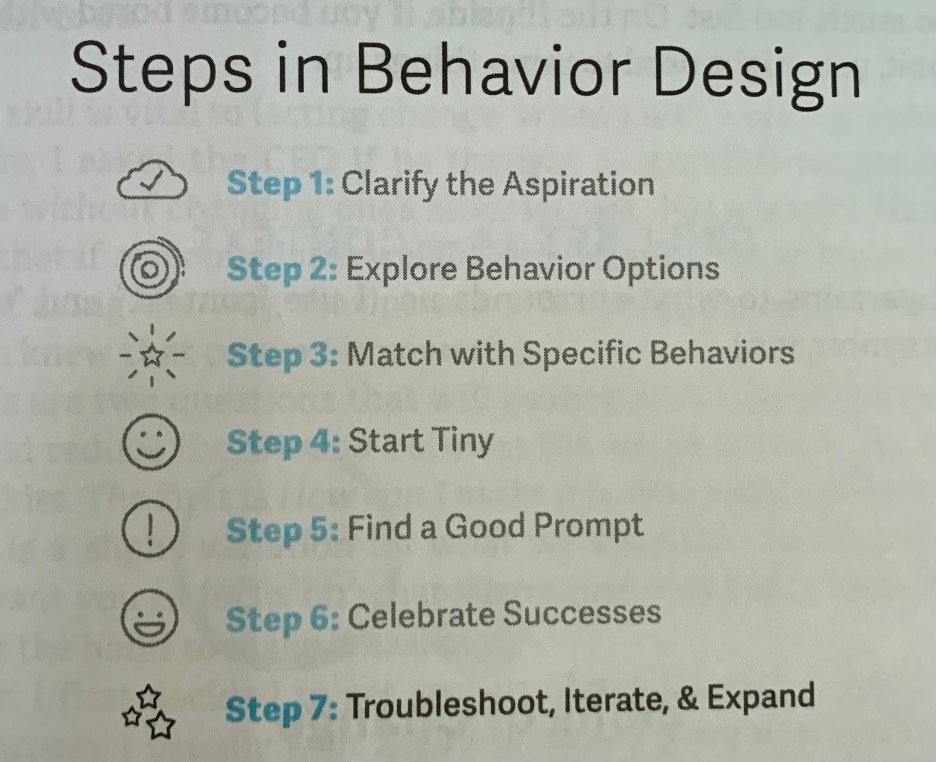

The first step in Behavior Design is to get clear on your aspirations (or outcomes). What do you want? What is your dream? What result do you want to achieve?

Write down your aspirations or outcomes and consider whatever you write as something you will probably revise.

STEP 2: EXPLORE BEHAVIOR OPTIONS

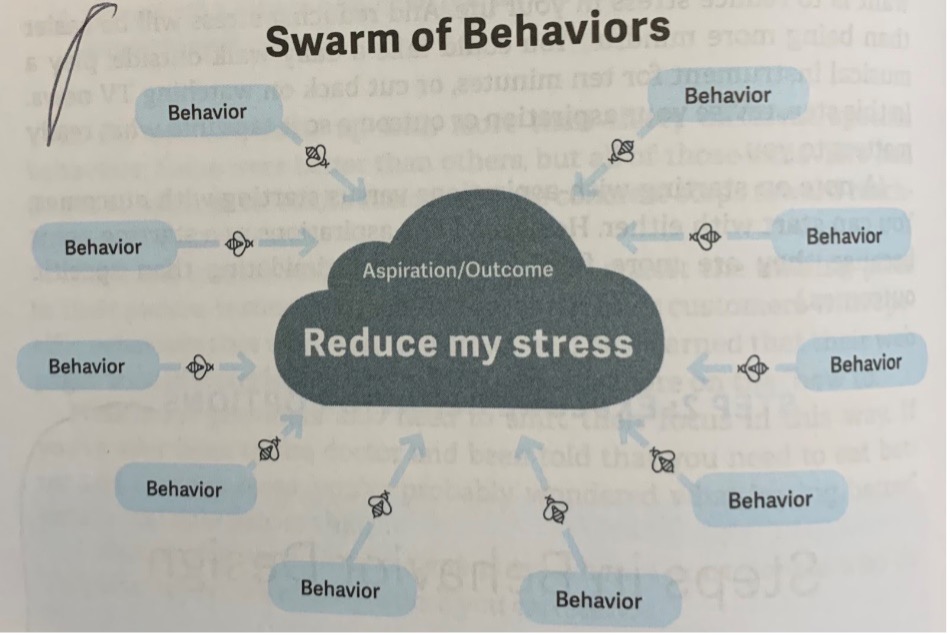

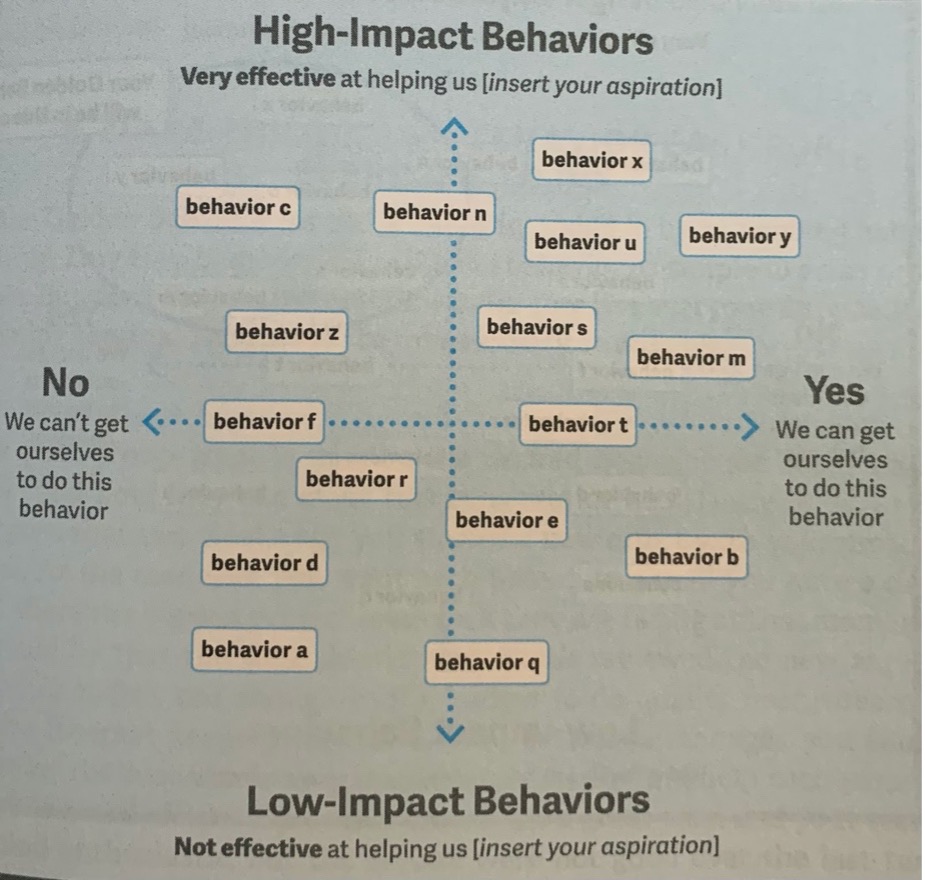

You get down to specifics in step 2. You select one of your aspirations, then come up with a bunch of specific behaviors that can help you achieve your aspiration.

You are not making any decisions or commitments in this step. You are exploring your options. The more behaviors you list, the better. You can tap into your creativity or maybe ask friends for their ideas.

I created a way to help people explore behavior options. This tool is called the Swarm of Behaviors (or Swarm of Bs). Here’s how it works: Write your aspiration inside the cloudlike shape shown in the graphic. Then start filling in the boxes with specific behaviors.

- What behaviors would you do one time?

- What new habits would you create?

STEP 3: MATCH WITH SPECIFIC BEHAVIORS

A Golden Behavior has three criteria.

- The behavior is effective in realizing your aspiration (impact)

- You want to do the behavior (motivation)

- You can do the behavior (ability)

Focus Mapping

Mark eyes his guitar-playing and work-leaving behaviors and asks himself: Can I get myself to do this?

The phrasing of the question is important. It brings together both motivation and ability at the same time. With this one question, you are addressing two components of my Behavior Model.

It’s this simple for a lot of behaviors. But for others, it helps to know what’s causing us to hem and haw.

To do this, ask yourself, Do I want to do this behavior?

Motivation, in other words.

You can’t get yourself to do what you don’t want to do. At least not reliably. You might do the behavior once or twice, but it’s unlikely to become a habit.

Behavior Design recognizes this reality: A key to lasting changes is matching yourself with behaviors that you want to do.

In Behavior Design we match ourselves with new habits we can do even when we’re at our most hurried, unmotivated, and beautifully imperfect. If you can imagine yourself doing the behavior on your hardest day of the week, it’s probably a good match. Is probably a Golden Behavior.

CHAPTER 3: ABILITY—EASY DOES IT

Notice that Krieger and Systrom nailed the motivation component by choosing a behavior that people already wanted to do.

they made their Golden Behaviors easy to do.

Krieger was fresh out of one of my classes at Stanford. He knew how human behavior worked and how important it was to make things easy to do if he wanted people to do them.

Sarika and the founders of Instagram were able to overcome a fundamental change myth and find success because they capitalized on the most reliable way to drive behavior—fiddling with the ability dial and making things easy. While I’m primarily focusing on habits in this book, making things easy to do will help you with almost any behavior.

Using Ability to Create Habits

We’ve already established that motivation is unreliable. Luckily, ability is not.

When you are designing a new habit, you are really designing for consistency.

If you want to do a habit consistently, you’ve got to adjust the most reliable thing in the

B=MAP model—ability.

Once I figured out my plan of action, regularly flossing my teeth was easy. But there is an underlying and beautiful complexity that made this all possible. I got to my solution by making flossing my teeth ridiculously easy to do, but first I have to understand what makes something hard to do. That’s why you should always start with this question: What is making this behavior hard to do?

What I found in my research and years of experience is that your answer will involve at least one of five factors. I call them the Ability Factors. Here’s how they breakdown.

- Do you have enough time to do the behavior?

- Do you have enough money to do the behavior?

- Are you physically capable of doing the behavior?

- Does the behavior require a lot of creative or mental energy?

- Does the behavior fit into your current routine or does it require you to make adjustments?

By asking what I call the Discovery Question, What is making this behavior hard to do? we are lasering in on which factor is likely to cause us the most trouble.

Almost everyone I meet has habits like this that elude them. Think about all the things you don’t do for your health, your productivity, and your sanity that you want to do. So why can’t you?

You can—with the right approach.

Ask the Discovery Question and identify the weak links in your Ability Chain. Then zero in on the right problem to solve.

Which leads us to the second critical question we should ask about any behavior or habit we want to cultivate: How can I make this behavior easier to do? I call this the Breakthrough Question, and it turns out that there are only three answers.

The Three Approaches to Making a Behavior Easier to Do

Molly reduced her Sunday food prep time from five hours to two and a half. Now she mandolins carrots, cucumbers, and peppers into Tupperware containers lined up for each day of the week.

Keep the Habit Alive

Making your behavior easy to do not only helps it take root so it can grow big, but it also helps you hang onto it as a habit when the going gets tough. Think of it this way: You can keep many tiny plants alive by giving them a few drops of water a day. It’s the same with habits. There are still days when motivation is unusually low for flossing. On those days, I floss only one tooth. The key is that I never feel bad about it because I’ve done my habit—I know one tooth is enough to keep the habit alive. Most days I do all of them, so I’m not about to sweat a day or two here and there. Stuff happens. People get sick, take vacations, and have emergencies. We’re not aiming for perfection here, only consistency. Keeping the habit alive means keeping it rooted in your routine no matter how tiny it is.

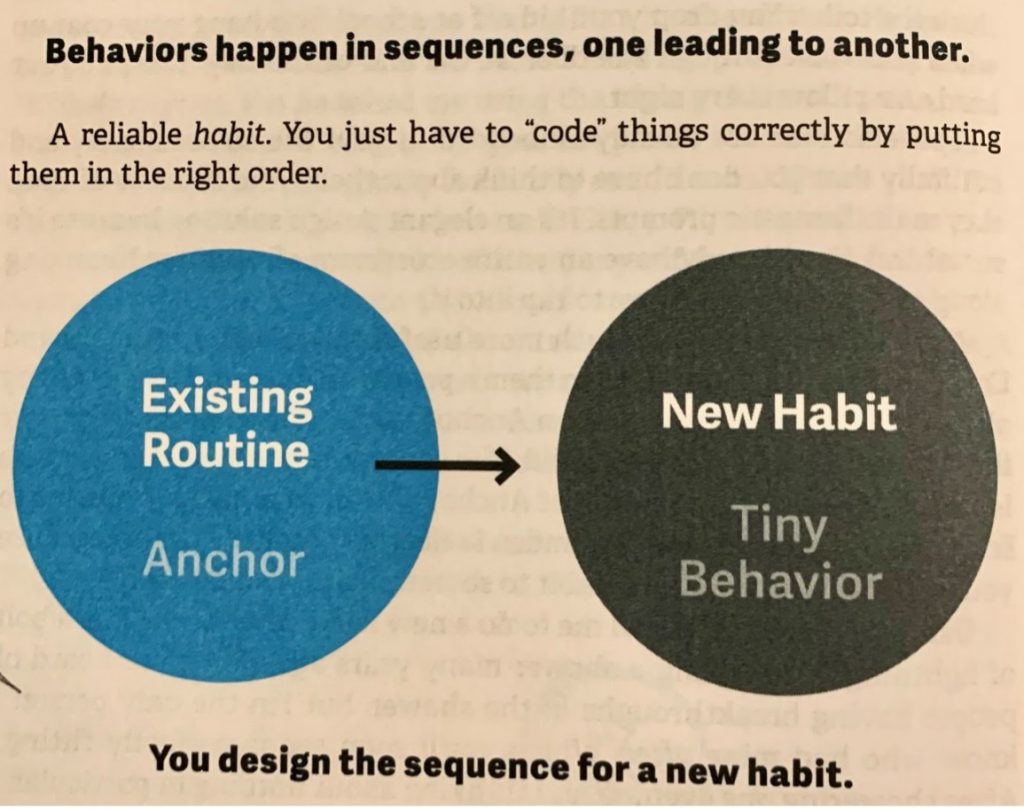

CHAPTER 4: PROMPTS—THE POWER OF AFTER

Whether natural or designed, a prompt says, “Do this behavior now.”

But this is the crucial nugget: No behavior happens without a prompt.

Where a habit is located in your daily routine can make the difference between action and inaction, success and failure.

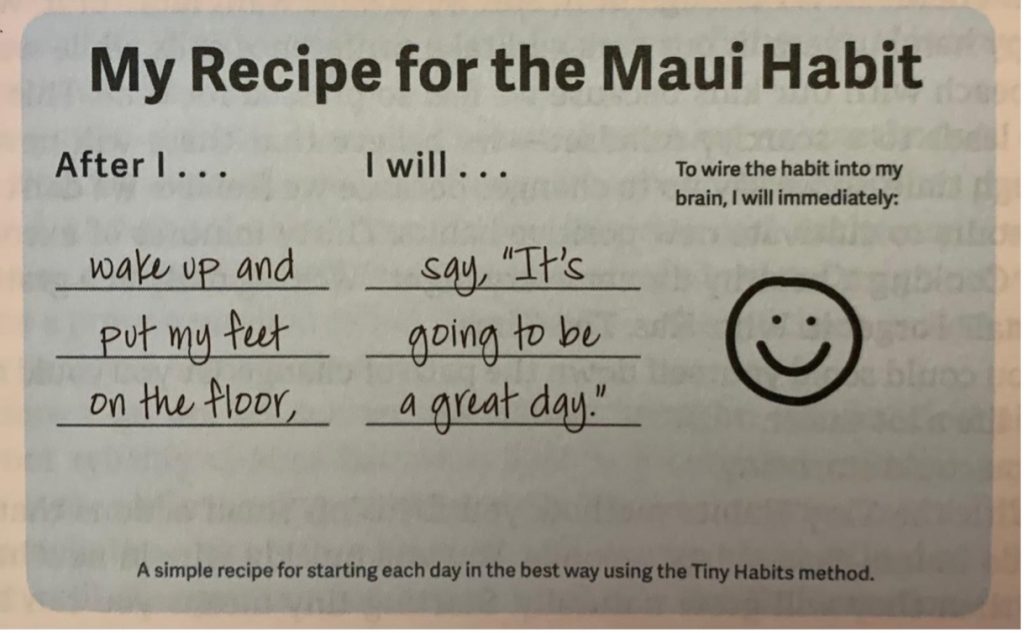

Here’s how it worked: Amy would drop her daughter Rachel off at kindergarten every morning, and Rachel would wave goodbye and shut the car door. The door shutting was Amy’s prompt. She would immediately drive to a nearby parking space at the school, then she’d do her habit—writing down her most important task on a Post-it. Once she was done, Amy would stick the note to her dashboard, clap once for herself, and say, “Done!”

A Systematic Approach to Prompts

There are three types of prompts in our lives: Person Prompts, Context Prompts, and Action Prompts.

This prompt type relies on something inside of you to do a behavior. Basic bodily urges are the most natural Person Prompts we have. Our bodies remind us to do necessary things like eat and sleep. That pressure in your bladder? Yep, that’s a prompt. Grumbling stomach—prompt. Thanks to evolution, these prompts are pretty reliable in getting us to take action.

Let’s say you want your daughter to do her homework every night instead of spending an hour on her phone. Asking her to remember to do that isn’t the best strategy because Person Prompts are not reliable.

This prompt is anything in your environment that cues you to take action: sticky notes, app notifications, your phone ringing, a colleague reminding you to join a meeting.

You can learn to design these Context Prompts effectively. If I had entered our dinner appointment on my calendar with a pop-up reminder, Denny and I would have shown up on our neighbors’ doorstep at 6:00 p.m. with a fresh salad. Creating this Context Prompt would have taken me about twenty seconds. But if I had put “Go to Wanda and Bob’s for dinner” on my to-do list, that design would have probably failed because I don’t look at my to-do list when I’m deep into a project.

I searched for a solution to this problem and found my answer. I wrote each weekend task on a small plastic sticky about half the size of your typical Post-it. I placed all the stickers on a laminated page that was labeled WEEKEND TASKS. Now my typical routine on Saturday mornings is to get out the laminated sheet and put it on the kitchen counter. Simple. This sheet becomes my checklist for the weekend. As I do each task, I move the sticker to the back of the sheet so I see only the tasks I haven’t completed. On Sunday, when I finish the final task, I flip the laminated page over, put the final sticker on the page (victoriously!), and store my laminated sheet of tasks for the next weekend.

- Write on your bathroom mirror with a dry-erase marker.

Context prompts can be useful and effective at times, but they can be stressful. Managing our prompt landscape effectively is one of the biggest challenges in our modern lives. When you set up too many Context Prompts, they can actually have the opposite effect—you become desensitized and fail to heed the prompt. You end up not hearing notification dings and not seeing the sticky notes. It’s like living next to train tracks—at first the noise of the train is deafening, then … what train?

I have a huge whiteboard in my home office listing dozens of tasks that are organized by project and coded in different colors. It’s… a lot. In order to manage this visual and psychological avalanche, I cover up the prompts for the task I’m not doing with a movable curtain so I see only the prompts for what I need to do that day. I’ve learned that covering up all the other prompts makes me calmer—and more focused.

If you’ve created a Context Prompt and it’s not working, you are not doing anything wrong. You probably don’t lack motivation or willpower. Do yourself a favor—don’t blame yourself. Redesign the prompt instead. Find what prompt works for you.

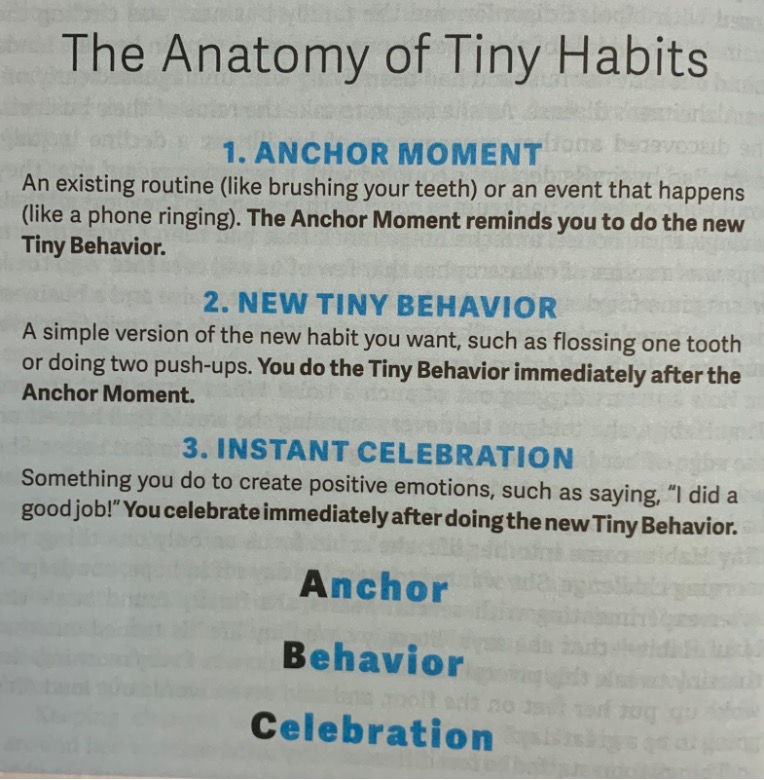

An Action Prompt is a behavior you already do that can remind you to do a new habit you want to cultivate. This is a special type of prompt.

Action Prompts are so much more useful than Person Prompts and Context Prompts that I have given them a pet name: Anchors. When talking about Tiny Habits, I use the term Anchor to describe something in your life that is already stable and solid. The concept is pretty simple. If there is a habit you want, find the right Anchor within your current routine to serve as your prompt, your reminder. I selected the term “anchor” because you are attaching your new habit to something solid and reliable.

The Recipe for Tiny Habits

After I (ANCHOR), I will (NEW HABIT).

Match the physical location

First, consider the physical location of your new habit. Find an Anchor that you already do in that location. If the new habit you want is wiping down the kitchen table, look for an existing routine in the kitchen. That could be your Anchor. You want to avoid having the Anchor happen in one location and the new habit in another. My research shows that this rarely works. Location is the most important factor when you pair Anchors and new habits.

Match the frequency

Power Move: Start with Anchors

Meanwhile Habits

After I turn on the shower (and while I wait), I will…

We all have these tiny pockets of time: after we stopped for a red light,

To discover good Action Prompts, start with a bit of research. Reach out to your two hundred best patients, those people who reliably measure and report their blood pressure. Ask them, “At what point in your daily routine do you typically take your blood pressure?”

Analyze their answers and look for trends. Let’s suppose that 26 percent of people say they measure their blood pressure after they sit down with coffee to read the morning newspaper. Another 21 percent report that they measure right after the feeding their pet. Then you find that 17 percent of patients take a measurement at the start of their favorite morning show on TV. But the remaining 36 percent of patients have a wide variety of answers with no clear trends.

You now have insights about what works with real people; you have data on what daily routines could serve as Anchors for the habit of measuring blood pressure. As you try to increase adherence, explain that many successful patients do this daily habit at one of three times.

Ask them, “Which one of these times would work best for you?”

In this way, you help your patients find where the new habit fits naturally into their lives.

This customizes the prompt for each person’s daily routine. You aren’t relying on patients to remember to check their blood pressure. You aren’t annoying them with notifications. And you aren’t hoping that they can figure this out on their own. You are using Behavior Design and the power of Action Prompts to help your patients be successful.

The scenario above may sound strange to you today, but I predict that this will be commonplace and essential in the future. Businesses that help customers create habits will have a huge advantage over those that don’t.

CHAPTER 5: EMOTIONS CREATE HABITS

In my research, I’ve found that adults have many ways to tell themselves, “I did a bad job,” and very few ways of saying, “I did a good job.”

I became increasingly convinced of the power of feeling good as the best way to create habits. I knew that people who embraced celebrations turned out to be the most successful at creating habits quickly. What’s more, people who celebrated were telling me how surprised they were that this one little shift made such a difference. People said that they started looking forward to doing their new habits just so they could celebrate. Some would ask me, “Is that crazy?” (No. It’s actually a very good sign.)

When you celebrate affectively, you tap into the reward circuitry of your brain. By feeling good at the right moment, you cause your brain to recognize and encode the sequence of behaviors you just performed. In other words, you can hack your brain to create a habit by celebrating and self-reinforcing. In my research I found that this technique had never before been named, described, or studied. I realized that by studying and teaching celebration I was breaking new ground to help people change for the better.

The time has come to say “hello” to feeling good.

Positive Experiences Reinforce Habits

A range of positive experiences can reinforce a new behavior that leads to a habitual response. For example, anything that gives you instant pleasure can reinforce the behavior and make it more likely to happen in the future.

Emotions Create Habits

There is a direct connection between what you feel when you do a behavior and the likelihood that you will repeat the behavior in the future.

In my own research, I found that habits can form very quickly, often in just a few days, as long as people have a strong positive emotion connected to the behavior. In fact, some habits seem to get wired in immediately: You do the behavior once, and then you don’t consider other options again. You’ve created an instant habit.

When I teach people about human behavior, I boil it down to three words to make the point crystal clear: Emotions create habits. Not repetition. Not frequency. Not fairy dust. Emotions.

Celebration is the best way to create a positive feeling that wires in your new habits.

The definition of a reward in behavior science is an experience directly tied to a behavior that makes the behavior more likely to happen again. The timing of the reward matters.

When you find a celebration that works for you, and you do it immediately after a new behavior, your brain repatterns to make that behavior more automatic in the future. But once you created a habit, celebration is now optional. You don’t need to keep celebrating the same habit forever. That said, some people keep going with the celebration part of their habits because it feels good and has a lot of positive side effects.

How to Celebrate the Tiny Habits Way

First of all, when I say that you need to celebrate immediately after the behavior, I do mean immediately. Immediacy is one piece of what informs the speed of your habit formation.

The other piece is the intensity of the emotion you feel when you celebrate. This is a one-two punch: you’ve got to celebrate right after the behavior (immediacy), and you need your celebration to feel real (intensity).

I believe my celebration technique is a breakthrough in habit formation. I hope you can see why. By skillfully celebrating, you create a feeling of Shine, which in turn causes your brain to encode the new habit.

WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU CAN’T FEEL IT

You may be thinking the same thing: Why should I congratulate myself on two push-ups, or flossing one tooth? The answer to this is threefold.

This is how the system of behavior works

Let’s say the TV in your living room is old. Sometimes it turns off for no reason. You smack it on the side and it turns back on. This doesn’t make sense to you, but it works every time. An engineer could probably tell you why this works, but it doesn’t matter because you got what you wanted—to finish watching your show. Behavior is also a system that has invisible components, but we know that dopamine is a key part of making habits stick. That’s how your brain works.

Celebration is a skill

Celebration might not feel natural to you, and that’s okay, but practicing this skill will help you to get comfortable. When I was learning to play the violin, my teacher showed me the proper way to hold the bow, but I resisted. I wanted to do it my way. She insisted that the only way for me to become proficient was to practice doing it the right way. I didn’t listen, and my progress stopped. I learned that she was right.

Three times to Celebrate

For the sake of simplicity, I tell people to celebrate immediately after they do a behavior they want to become a habit. But the truth is, you can become a Habit Ninja faster and more reliably by celebrating at three different times: the moment you remember to do the habit, when you’re doing the habit, and immediately after completing the habit. Each of these celebrations has a different effect.

Celebration Is the Bridge from Tiny Habits to Big Changes

Celebration will one day be ranked alongside mindfulness and gratitude as daily practices that contribute most to our overall happiness and well-being. If you learn just one thing from my entire book, I hope it’s this: Celebrate your tiny successes. This one small shift in your life can have a massive impact even when you feel there is no way up or out of your situation. Celebration can be your lifeline.

CHAPTER 6: GROWING YOUR HABITS FROM TINY TO TRANSFORMATIVE

The Dynamics of Growth

So with Tiny Habits you are shooting for a bunch of tiny successes done quickly.

Hope and fear are vectors that push against each other, and the sum of those two vectors is your overall motivation level.

The first time people do a behavior is a critical moment in terms of habit formation. If you feel like a failure running the meeting, your fear vector will get stronger, moving your overall motivation level down so it’s likely that you won’t want to lead meetings in the future.

But your story is different. You do an amazing job leading the meeting. You get a lot done, and your colleagues compliment you on your style. This is where the feeding of success plays a powerful role. If you feel successful in running the meeting, the demotivator of fear will get weaker or it might vanish entirely. Your overall motivation level will increase. Now that you are consistently above the Action Line, you say yes to your great new habit of directing more meetings.

But that’s not all.

When a demotivator goes away, you open the door to a bigger and harder behavior. The Action Line on my Behavior Model shows that you can do harder behaviors as your motivation levels rise. If you vanquish the fear of running meetings, you are more likely to say yes when your boss invites you to lead company-wide meetings, which is a harder behavior because it takes more time, energy, and thinking—but now your hope surges. As a result, you run big meetings and your career advances.

I now understand why my Tiny Habits data showed so many breakthroughs. When people feel successful, even with small things, their overall level of motivation goes up dramatically, and with higher levels of motivation, people can do harder behaviors.

You can practice this skill by answering one question: What is the tiniest habit I could create that would have the most meaning?

The skill of redesigning your environment to make your habits easier to do

This skill is vital to lasting change. When I was working with Weight Watchers, I asked the CEO if he thought sustainable weight loss was possible without changing one’s environment. His answer? No way. We agreed that if someone loses weight and doesn’t change his or her environment along the way, that person will eventually regain the weight. We both knew that context is powerful.

When you consciously and thoughtfully design your environment to accommodate new habits, you make your whole life easier.

- Finish the sentence “I’m the kind of person who” with the identity — or identities — you’d like to embrace.

- Go to events that gather people, products, and services related to your emerging identity.

- Learn the lingo. Know who the experts are. Watch movies related to the area of change you’re interested in.

EXCERCISE #6: PRACTICE A SELF INSIGHT SKILL

One important Self-Insight Skill is finding the smallest changes in your life that will have the biggest meaning. I believe this exercise is the toughest one I’ve suggested, and that’s why I saved it for last.

Step 1: List an area of life that really matters to you, such as being a good mom or showing compassion.

Step 2: Spend 3 minutes thinking about the simplest one-time behaviors you could do that would have significant meaning in that area. Make a list.

Step 3: Repeat Step 2, but this time consider the tiniest new habits that would have the most significance to you in that area. Make a list.

Extra credit: Decide what items from steps 2 and 3 you want to put into practice.

CHAPTER 7: UNTANGLING BAD HABITS: A SYSTEMATIC SOLUTION

A helpful way to think about habits is to put them into three categories. I’m talking about all habits here— good and bad. Uphill Habits are those that require ongoing attention to maintain but are easy to stop—getting out of bed when your alarm goes off, going to the gym, or meditating daily.

Downhill Habits are easy to maintain but difficult to stop—hitting snooze, swearing, watching YouTube.

Freefall Habits are those habits like substance abuse that can be extremely difficult to stop unless you have a safety net of professional help.

To get rid of your Downhill Habits, I’ve created a new system called the Behavior Change Masterplan. This system provides a comprehensive approach to follow step by step so you don’t need to guess at solutions.

Instead of “break”, I suggest a different word and a different analogy. Picture a tangled rope that’s full of knots. That’s how you should think about unwanted habits like stressing out, too much screen time, and procrastinating. You cannot untangle those knots all at once. Yanking on the rope will probably make things worse in the long run. You have to untangle the rope step by step instead. And you don’t focus on the hardest part first. Why? Because the toughest tangle is deep inside the knot.

You have to approach it systematically and find the easiest knot to untangle.

Junie first listed all the tangles in her sugar habit not. Then she addressed the most inaccessible one— going without dessert after dinner

Traditional change methods (the ones that work, anyway) also fit in my overall masterplan. Consider motivational interviewing, a counseling method that helps clients get clear on their motivations. This is one of the few traditional approaches I find worthwhile. People who experience motivational interviewing can better understand their reasons for doing or not doing a behavior.

If you’re trying to cut down screen time, an accountability partner might suggest you install a timer that turns off your Wi-Fi at eight p.m.

You can stop a behavior by altering any of the three components of the Behavior Model. You can decrease motivation or ability, or you can remove the prompt.

However, after you list specific habits that relate to your general habit, untangling this big bad habit will feel more manageable.

The answer is so important, I’ll say it three times in different ways: Pick the easiest one. Pick the one you are most sure you can do. Pick the one that feels like no big deal.

People are often tempted to pick the hardest, stickiest habit to unwind, but that is a mistake. That’s like trying to untangle the tightest snarl deep inside a big knot. Start with the specific habit that will be the easiest for you to stop instead.

Focus on the Prompt to Stop a Habit

Sometimes all you need to do is tackle the prompt and you’re done, and there are three ways to do this: remove the prompt, avoid the prompt, or ignore the prompt.

- Don’t go places where you will be prompted

- Don’t be with people who will prompt you

- Don’t let people put prompts in your surroundings

- Avoid media that prompts you

In our Maui home, we don’t have a TV that’s easy to watch. We have one, but it’s stored away. And that’s by design. In order to watch TV, I have to get it out of storage, physically carry it to a spot in the living room, and plug in the cables. Making this hard to do means that we never turn on the TV randomly. We watch only when we decide it’s worth the trouble.

Does this always work? No. But does logging calories require more mental effort than mindlessly eating? Yes. And that’s one reason it can work.

CHAPTER 8: HOW WE CHANGE TOGETHER

Even so, I want to offer you my special chapter on Tiny Habits for Business Success, which you can get by going to TinyHabits.com/business.

People change best by feeling good, not by feeling bad

Feedback from authority figures is powerful, and approval from authority figures can open the door to transformation. If you can give feedback at the right moment to help people feel successful, you can create a habit of the good behavior. But that’s not all. As I shared in chapter 5, the effects of feeling successful ripple out. There is no more powerful praise than what comes from someone we admire and trust. And for some people, that person is you.

One of my personal themes for the last year has been to “strengthen others in all my interactions”. And I even have a beautiful painting in my home office with these words on it (thanks, Stephanie). I apply my research insights in pursuing this aspiration, and I try to strengthen others by giving well-timed feedback to people around me: when one of my students gives her first presentation in class, when my partner cooks a new dish, and when someone phones with a question about my work. In all these situations, I have a huge opportunity to strengthen these people—they care about a topic, and they are uncertain. All I have to say is something positive that is sincere. Too often people give negative feedback in vulnerable situations. The start of your presentation was too slow. This fish is a little dry; how long did you cook it? I can tell from your question that you really haven’t read my work.

Yikes. Don’t do that.

Be a good Ninja.

Three Hundred Recipes for Tiny Habits — Fifteen Life Situations and Challenges

You can see more recipes at TinyHabits.com/1000recipes.

TINY HABITS FOR WORKING MOMS

- After I hear my alarm, I will turn it off immediately (no snooze).

- After I put my feet on the floor in the morning, I will say, “It’s going to be a great day!”

- After I walk into the kitchen, I will drink a big glass of water.

- After I start the coffee maker, I will get out the lunch boxes.

- After I get the eggs cooking, I will set out my vitamins.

- After I turn on the shower, I will do three squats (and maybe more).

- After I make my bed, I will put clothes into the washer and set a timer.

- After my children leave for school, I will get out my to-do list for work.

- After I buckle my seat belt, I will press play on my audiobook.

- After I pull into the parking lot at work, I will park in the farthest parking space.

- After I sit down at my desk, I will put my phone on airplane mode.

- After I sort through my spam folder, I will walk around and quickly greet my teammates.

- After I get back to my desk after my morning meeting, I will list my top priority for the day.

- After I eat lunch, I will walk around the building at least once.

- After I put my computer to sleep at the end of the day, I will tidy my work desk quickly.

- After I drive out of the parking lot at work, I will turn toward the gym.

- After I walk in the door after work, I will give my children a hug.

- After I start the dishwasher, I will tidy up at least one thing on the counter.

- After I say goodnight to my children, I will think of one person I love whom I might call.

- After I get in bed, I will open the scriptures and read at least one verse.

TINY HABITS FOR NEW MANAGERS

14. After I head out for a meeting, I will offer a positive comment to the front-desk associate.

15. After an employee comes to me with a problem, I will say, “What do you think is the best way forward?”

TINY HABITS FOR WORK TEAMS

- After we arrive at work, we will park in the farthest spot.

- After we turn on our computers, we will check our voice mail.

- After we draft an e-mail with sensitive information, we will double-check that it’s being sent to only necessary recipients.

- After we submit the quarterly update, we will high-five a contributing team member (virtually or in person).

- After we hear negative feedback from a customer, we will say this exact script: “Thank you for the valuable feedback. I will share that with my team.”

- After we receive positive feedback from a customer, we will print that e-mail and pin it to the kudos board in the break room.

- After we schedule a team meeting, we will send out an e-mail asking for agenda items.

- After we return to our desks from using the toilet, we will clear one item from our desks.

- After we arrive at a meeting, we will put our phones on do not disturb mode.

- After we adjourn a meeting, we will push in the chairs in the conference room.

- After we clean the whiteboard, we will check the table for trash or loose papers.

- After an employee brings up a problem, we will say, “What do you think is the best way forward?”

- After a meeting is about to end, we will ask, “What’s one surprise from today’s meeting?” and hear each team member’s reply.

- After we take the last item of an office supply, we will email the administration lead with the details about the item in need.

- After we select the date for the monthly staff potluck, we will send out the who’s-bringing-what sign-up sheet.

- After we finish eating in the break room, we will wipe down one countertop.

- After we onboard a new hire, we will walk them around the office and make brief one-on-one introductions.

- After we close our computers down, we will file one stack of papers.

- After we shut down our computers, we will lock our filing cabinets.

- After we close the office for the day, we will make sure the lights, fans, and heaters are all powered down.

TINY HABITS FOR BEING MORE PRODUCTIVE

- After I open my calendar for the day, I will get out one file related to the day’s agenda.

- After I sit down at my desk, I will put my phone on do not disturb mode.

- After I close my office door, I will organize one item that’s lying around.

- After I finish reading e-mail, I will close the e-mail browser tab.

- After I launch a new Word doc, I will hide all other programs running on my computer.

- After I find myself mindlessly browsing social media, I will log out.

- After I sit down at a meeting, I will write the title, the date, and the attendees at the top of my notes.

- After I notice a call going on for longer than expected, I’ll say this script: “It’s been great to talk, but I need to wrap up. What haven’t we covered yet that’s important?”

- After I read an important e-mail, I will file it in the folder for the designated project.

- After I read an e-mail I can’t deal with immediately, I will mark it as unread.

- After I read an e-mail that’s time sensitive, I will reply with the script: “Got it. I will review in detail and get back in touch soon.”

- After I shut down my computer, I will ready one file for the next day’s agenda.

- After I pack my work bag, I will review my whiteboard and calendar.

- After I leave the office, I will think about one success from the day.

- After I walk in the door at home, I will hang my keys on the hook.

- After I walk into the kitchen, I will plug my phone into the charger.

- After I change out of my work clothes, I will hang or organize one item I was wearing.

- After I review a bill, I will add it to the to-pay envelope.

- After I get out my stack of bills, I will get out the basket with my checkbook, pen, envelopes, and stamps.

- After I start the shower at night, I will think, Why am I so incredibly productive?

TINY HABITS FOR STRENGTHENING CLOSE RELATIONSHIPS

- After I make the bed, I will give my spouse a hug.

- After I finish flossing, I will write a little love note on the mirror in dry-erase marker.

- After I take a coffee break midday, I will text my spouse a message of appreciation.

- After I listen to a great podcast, I will send the link to the episode to my best friend.

- After I see a neighbor, I will wave and ask them, “What’s new and what’s good?”

- After I sit down to coffee with a friend, I will ask her a specific question about her life.

- After I see the card aisle at the grocery store, I will select one “thinking of you” card to send to someone I love.

- After I see online that a close friend has a birthday, I will send that person a quick audio text with a happy message.

- After I balance the monthly budget spreadsheet, I will compliment my partner on one specific aspect of how they contributed to our success.

- After I arrive home from work or errands, I will hug my spouse and kids.

- After I hear my partner complain about an ache or pain, I will offer to rub their back for a moment.

- After I hear about my spouse’s stressful day, I’ll say this: “I’m here for you.”

- After I thank God for the dinner we are about to eat, I will express gratitude for my spouse and family in prayer.

- After I leave church, I will call my parents on the ride home.

- After I make a special trip to see family, I will share a few photos in an e-mail note to say a quick thanks.

- After I leave an event with a close friend, I will send them a quick text thanks.

- After I make a homemade baked good, I will take a portion of it to a neighbor or friend.

- After a gift arrives from my kids, I will send a quick text saying, “Got X. Wow, so thoughtful. Thank you!”

- After I plan a day trip for my partner and myself, I will ask my partner if there’s anything special he or she would like to see or do.

- After I pack for a weekend getaway, I will pack a special surprise for the people I’m visiting.

TINY HABITS FOR STAYING FOCUSED

- After I walk in the door at work, I will switch my phone to airplane mode and store it in my backpack.

- After I set my backpack down at work, I will pick an important task that I want to do immediately.

- After I pick my important task, I will clear my desk of all distractions.

- After I clear my desk, I will set a timer for forty-five minutes.

- After I set my timer, I will put on my headphones to signal to others that I shouldn’t be disturbed.

- After I put on my headphones, I will close all unnecessary windows on my computer.

- After my timer goes off, I will list what my next task should be and take a break.

- After I sit outside during break, I will meditate for three breaths or longer.

- After I come back into the office, I will pour some fresh coffee.

- After I check for urgent messages, I will turn on the e-mail auto reply that says I’m away from e-mail.

- After I decide to go to lunch, I will write down the next step on my project (what to immediately do after I return).

- After I sit down for lunch at the cafeteria, I will check for any urgent personal messages.

- After I put away my lunch utensils, I will walk around outside and recharge.

- After I check for urgent e-mails after lunch, I will turn on the e-mail auto reply that says I’m away from e-mail.

- After I pick the next project to do, I will quickly list the steps in the project.

- After someone asks me to run an errand with them, I will say, “I can’t right now. Sorry.”

- After I finish my afternoon snack, I will set a timer for a ten-minute nap.

- After I go into our project room, I will close the door and put up the DO NOT DISTURB sign.

- After the project meeting begins, I will start taking notes (so I stayed tuned in).

- After I walk out the door at to go home, I will say, “Why am I so good at staying focused?”

TINY HABITS FOR BUSINESS TRAVEL

19. After I sit down on the plane headed home, I will make a list of people to thank from my business trip.