The Power of Fifty Bits: The New Science of Turning Good Intentions Into Positive Results

Bob Nease

Introduction

How Jack Changed My Life

But for now it’s worth pointing out how fifty bits design is different from other design approaches–namely, user-centered design. As you will soon see, fifty bits refers to a startling statistic: of the ten million bits of information our brains process each second, only fifty bits are devoted to conscious thought. I This limitation means that, to a large degree, humans are wired for inattention and inertia, which in turn leads to a gap between what people really want (were they to stop and think about it) and what they do.

Fifty Bits Design Versus User-Centered Design

Fifty bits design is very different, and we’ll go into the differences in greater depth in the last chapter of the book. For now, it’s important to note that rather than start with what the user wants from the interaction, fifty bits design starts with what the designer wants from the user. Unlike user-centered design, fifty bits design assumes that users may not really know what they want, and even if they do, they might not put the effort into actively pursuing it. Fifty bits design assumes that much of the time, users’ behavior is disconnected from what they’d want if they spent more time thinking about things.

Chapter 1: Wired for Inattention and Inertia

The Intent-Behavior Gap

The fundamental idea of The Power of Fifty Bits is that for better or worse our brains are wired for inattention and inertia, not for attention and choice. This point is critical for those of us who are trying to improve behavior, because most of the time we act as though people have an infinite appetite for information and a boundless willingness to make decisions. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Once you understand and believe in the fifty bits way of looking at the world, a lot changes. You stop focusing on trying to change behavior by changing intentions. Instead, you start focusing on strategies that activate the good intentions that already exist for more people.

Chapter 2: Behavioral Shortcuts

Shortcut #1: Fit In

Not only does Julie get me to say yes to the cookies, she does it with a vengeance. She presents me with a list of the names of my neighbors who have also been victims of the Great Cookie Shakedown, along with the precise number of boxes of cookies they’ve each agreed to buy. I find myself scanning the list for Ed (the fellow a few doors down who has a nicer yard) and note that he’s down for six boxes. I up the ante and proudly announce to Julie by decision to buy seven boxes. That will show Ed, for sure.

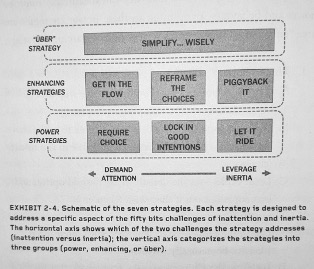

The Seven Strategies for Fifty Bits Design

Chapter 3: Require Choice

How One Charity Skated Through the Recession

This approach is known as active choice. When using active choice, people are stopped in the middle of a process and are required to make a choice among two or more alternatives. In the case of PetSmart’s charity, that means requiring customers to make a decision about donating to help homeless pets. Rather than trying to convince their customers that donating money for animals is better than not making a donation, their application of active choice simply requires people to consciously decide whether or not to donate–thus tapping any latent demand for charitable giving for homeless pets.

Similarly, many ATMs ask customers during their transaction whether they would like a receipt printed. Businesses are using active choice because it works. They realize that there is a gap between underlying intentions and everyday behavior, and that one powerful way to close that gap is to simply stop their customers and ask them to make a choice. The more you understand active choice, the more you begin to see its application in everyday life.

The Puzzle of Home Delivery for Prescription Drugs

Fifty bits also explains why active choice is so powerful: we told people that we needed their attention just long enough for them to make an explicit choice about where they wanted to get their medications. This approach tapped the hidden interest in home delivery among those using retail. No forcing, no persuading… just getting their fifty bits pointed in the right direction long enough to make a decision.

Designing With Active Choice

There are three main steps for bringing active choice to life: interrupting an existing process, presenting the key choices, and executing on the choice that the person makes.

Designing for active choice–stopping people briefly, “grabbing” their fifty bits, and having them tell you what they want–can effectively close the gap between what people want when they stop to think about it and what they do otherwise due to inertia and lack of attention.

Chapter 4: Lock In Good Intentions

Removing the television sets today to avoid the temptation of watching too much TV in the future is a type of precommitment. Precommitment is a decision made in the present that advantages better behavior in the future. Often, this goal is achieved by making an especially tempting option that one would later regret (e.g. watching hours of junk TV) impossible, difficult, or expensive.

Designing With Precommitment

Applying precommitment to a specific behavioral challenge is very much like applying active choice, but with a twist: the decision you’re asking people to make is whether or not to make a tempting, suboptimal option in the future costly or impossible. Accordingly, there are three key steps in applying precommitment: identifying a tempting future behavior, allowing people to choose to make that option impossible or less desirable, and executing on the choice that they make.

Chapter 5: Let It Ride

Bigger, Better Nest Eggs

And it worked like a charm, with 401(k) participation rates jumping from below 40 percent to as high as 90 percent. In addition, employee satisfaction remained exceptionally high, even among those employees who decided not to participate in the plan.

Designing Using Opt-Outs

To help demonstrate how to put opt-outs to work, let’s imagine that we are in charge of a neighborhood homeowners association. As part of that role and in consultation with current homeowners, we have decided on a minimum set of maintenance activities to which all homeowners contribute via annual association fees that are automatically charged to a credit card each owner provides. These routine activities include street maintenance and repairs, landscaping of common areas, periodic collection of leaves in the fall, snow plowing of the private streets in the winter, and the like.

We noticed that almost all the homeowners in the association hire help to clean their roof gutters in the spring. Because this activity isn’t coordinated, the street sometimes becomes busy with trucks from multiple companies. We’ve also heard from a handful of homeowners that they forget to clean their gutters.

To address this problem, we decide to bid out the gutter cleaning business for the entire street. This will allow all of the homeowners who participate to enjoy better pricing and will also reduce traffic.

margin note – for the hunt

Chapter 6: Get in the Flow

Facings and placement make a difference when it comes to packaged goods. A series of studies from INSEAD and Wharton, for example, found that “for the average brand and consumer, doubling the number of facings increasing noting by 28%, reexamination by 35%, and choice and consideration by 10%.” We can all do the math: a 10 percent increase in how often your product gets chosen in a $10 billion market is nothing to sneeze at.

Cues for the Clueless, Clues for the Cue-Less

You’ve used this fifty bits design strategy. You’ve put something you want noticed–we’ll call it a cue, because it’s a call to some type of action–in the natural flow of someone’s fifty bits.

Amazon and Netflix both understand the power of getting in the flow of the attention of their users. Both companies mine their enormous stores of behavior data and ratings (for products or movies) to make accurate and specific recommendations for individual customers. They know that your digital screen has your precious 50 bits, and they treat your attention as the scarce resource that it is: they deliver relevant recommendations in which you are likely to be interested.

Designing by Getting in the Flow

Remember, the idea of getting in the flow is to go where someone’s attention is already pointed, so the first step is to find such a place. If your cue (i.e., reminder or call to action) is visual, you want to find a place someone is already looking. If auditory, it will be a place or time someone is already listening.

Getting in the flow works the best when you’re tackling inattention. If the problem is not inattention but instead is inertia–that is, the desired behavior is effortful in the present but offers a payoff in the future–consider using opt-outs, providing the opportunity for precommitment, or requiring choice. For our example, we will assume that the obstacle to the husband picking up the diapers is that he simply forgets to do it after being asked.

Chapter 7: Reframe the Choices

Possibly The Best Public Service Announcement… Ever

The tagline was about pollution, but the emotional connection was to littering. This is called telescoping, and it is a powerful way to connect with people. It’s what public radio stations do when they ask us to pledge a dollar a day, stating “that’s less than you pay for a cup of coffee.”

Two Magic Words in Customer Service

We ordered, and the server said, “That’s great. I will get that right out for you.”

Bobby laughed and said, “That’s a total customer service line.” I asked him what he meant, and he said that the lead of their customer service team had taught all the new agents to periodically add the words for you when affirming a customer’s request.

Just think about the difference between these two statements:

“I will get that right out.”

“I will get that right out for you.”

Those two little three-letter words tacked on to the end of the sentence do a fair amount of work. They gently move the conversation from one centered on a transaction (you pay for the meal, I bring the food) to one centered more on a social interaction (you’re celebrating a new job, I will make it special.)

Reframing Choices Using Social Norms

A couple of members of the Express Scripts Consumerology Advisory Board–a select group of some of the nation’s leaders in the behavioral sciences–have done some really interesting work in this regard.

Reframing Choices Using Loss Aversion

Here’s an example from my Experience at Express Scripts. We realized that many patients had an opportunity to save money by switching from a more expensive brand of medication to an equally effective but lower cost generic option. Loss aversion suggests that people work harder to avoid losses than they do to pursue gains; framing tells us that words matter. So instead of talking about the money patients could save by making the switch to the lower-cost option, we reframed the communication to emphasize the money they were losing by not making the switch. Specifically, we likened using an expensive branded medication when a less expensive option is available to “burning money.” The approach worked, nearly doubling the performance of the communication.

Chapter 8: Piggyback It

The sixth strategy in the arsenal of the fifty bits designer is piggybacking. Rather than tackle the desired behavior head-on, piggybacking makes that behavior the side effect of something that people are already likely to pursue or enjoy. With piggybacking, the behavior we desire “catches a ride” with something that we know that people want to do. In the case of the polio vaccine, receiving a vaccination piggybacks on eating a sugar cube.

The Power of Mint

In other words, prevention of cavities in the future–the real health benefit of daily brushing–is piggybacking on the clean feeling that tooth brushing generates in the here and now.

Chapter 9: Simplify Wisely

Fluency can also be affected by the names we give things. Stock prices of companies with easy-to-pronounce names do a lot better on the day they go public than prices of companies that are hard to pronounce. REcipes printed in hard-to-read fonts are judged by readers to take longer to prepare than those printed in easier-to-read fonts, and roller coasters with tough-to-pronounce names are judged to be more risky to ride. On the Express Scripts website, we found that the more explanatory text we included about potential savings opportunities, the less successful we were at getting patients to make a change; a preliminary study found that (made-up) drugs with hard-to-pronounce names were not viewed as favorably as those with easier-to-pronounce names, which may be a built-in disadvantage for generic medications.

Why Easy Isn’t Always Better

If the desired choice is the one that people are likely to accept only after stopping and really thinking things through, you may be better off decreasing the fluency of the overall choice process.

Designing with Wise Simplification

The first step in wise simplification is to make the preferred choice or behavior as easy as possible, including how any information is presented. To make use of the stairs as easy as possible, we will recommend that the company make the staircase easy to find, well illuminated, and visually appealing.

Next, if you believe that people are still likely to select a nonpreferred option, consider redesigning the choice process to introduce disfluency. For example, we suggest placing the elevators as far away from the entrance as the building, ADA, and fire codes allow, and we recommend the use of signage that requires those who are inclined to use the elevators to slow down just a bit.

If people are headed in the right direction, easy is your friend: use more of it; make the interactions fast and frictionless. If people are headed the wrong direction, or if it’s difficult for people to know which option is best without more deliberate thought, however, then easy is probably your enemy: you want less of it.

margin note– email my mgr say I (won’t join?)

Chapter 10 : Forging a New Science for Better Behavior

Contraceptive technology, however, has fallen short of its full potential. Half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended–a whopping 3.4 million per year.

The Contraceptive Choice Project

Reframe the choices. CHOICE used tiered counseling–a type of “order framing”–very effectively in counseling young women about their contraceptive options. The researchers were surprised to find that most physicians started their discussions with women by focusing on either the method the patient was currently using or the one with which the patient was most familiar. Much of the time, this meant anchoring the discussion around oral contraceptives, which are effective but only when taken religiously. Instead, the CHOICE staff developed an approach in which all of the methods were presented in their order of effectiveness, starting with the most effective methods and working their way down to the least effective methods. The result is that effectiveness remains front and center in how women are thinking about contraception, and that any trade-offs that are made are done so in light of effectiveness.

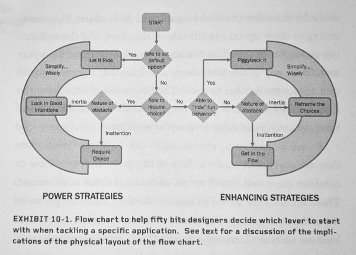

Making the Most of Fifty Bits Design

The practice of fifty bits design is still somewhat new, but experience to date suggests a set of questions that can help determine which of the strategies is likely to be the best suited for any specific application you might be considering. Exhibit 10-1 captures as a flow chart the strategies I suggest you use in different circumstances. As you work your way through the chart, you will arrive at a single suggested strategy.

A careful look at the flow chart reveals a couple of important points. First, the chart prioritizes the use of “power” strategies, at least when they are suitable. In other words, if it’s possible to use those strategies, the chart will suggest that you start there. Second, the chart helps you think about the nature of the main obstacle that keeps people from engaging in the desired choice or behavior. If the issue is inattention, one strategy will be suggested; if it’s inertia, another will be suggested. Together, these two points (prioritizing the use of the power strategies over the enabling strategies, and inattention vs. inertia as the main obstacle) drive the physical layout of the flowchart.

A Better Way to Better Behavior

Fifty bits design takes a starkly different path, and in doing so offers of bold set of new solutions for improving behavior. It rejects the assumptions that we are poorly educated, hoodwinked by others who are in the know, inadequately incentivised, resistant to change, or of questionable moral character. Instead, fifty bits design rests on a single scientific reality: our brains are the products of evolution, and as a result are adapted for an environment that in many ways no longer exists. All too frequently, our brains act like fish out of water. Unfortunately, the natural inclinations that served us so well in a time long ago and a place far away now routinely lead us astray. Today ‘s world demands deeper attention and more frequent decision-making, but our brains are instead wired for inattention and inertia. These limitations lead to a persistent gap between our internal intentions and our outward actions.