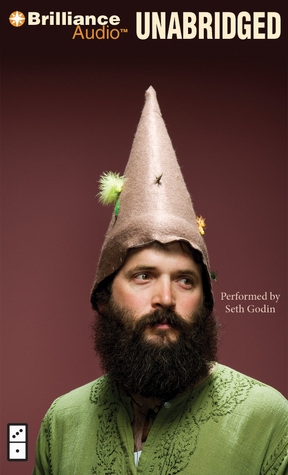

We Are All Weird: The Myth of Mass and The End of Compliance

Seth Godin—2011.

Introduction: The Pregnant Elephant

- Two decisions you’ll need to make within the hour:

- 1. Do you want to create for and market to and embrace the fast-increasing population that isn’t normal? In other words, which side are you on—fighting for the status quo or rooting for weird?

- 2. Are you confident enough to encourage people to do what’s right and useful and joyful, as opposed to what the system has always told them they have to do? Should we make our own choices and let others make theirs?

Part one: capitalism, industry and the power of mass – and its inevitable decline

- Mass wasn’t always here. In 1918, there were two thousand car companies active in the United States.

- At its heyday, on the other hand, Heinz could expect that more than 70 percent of the households in the U.S. had a bottle of their ketchup in the fridge, and Microsoft knew that every single company in the Fortune 500 was using their software, usually on every single personal computer and server in the company.

Part two: the four forces for weird

- Force one: Creation is amplified.

- Publish a book or sell a painting or customize your car or design a house—whatever your passion, it’s easier to do it, it’s faster to do it, and it’s more likely that (part of) the world will notice what you do. The ability to reach and change those around you has been changed forever by the connections of the Internet and the fact that anyone, anywhere can publish to the world.

- Force two: Rich allows us to do what we want

- Only wealthy organisms are able to culturally diversify, and as human beings get richer and richer, our instinct is to get ever more weird. As productivity has skyrocketed, so has our ability to do what we’d like instead of merely focusing on survival.

- Force three: Marketing is far more efficient at reaching the weird.

- The long tail isn’t just a clever phrase; it’s an accurate description of the market for just about everything.

- Force four: Tribes are better connected.

- Because you can find others who share your interests, weird is perversely becoming more normal, at least in the small tribes that we’re now congregating in. The community you choose can be a mirror and an amplifier, furthering your interests and encouraging you to push ever further. The Internet connects and protects the weird by connecting and amplifying their tribes.

- For just a hundred dollars more than that, anyone can buy a month-long JetBlue travel pass.

- ‘The Pro-Am revolution—the increasing impact of amateurs working to professional standards.

- The Pew Internet and American Life Project reports on the habits of millions of internet users. According to the report, “Many enjoy the social dimensions of involvement, but what they really want long to in the past year and just under half say they accomplished something they couldn’t have accomplished will on their own.”

- As a result, the mass marketer keeps missing the point. He’s busy looking for giant clumps instead of organizing to service and work with smaller tribes.

- In addition to being able to make what the market desires, this new breed of marketers are also far better at figuring out what the market desires. And as they identify and connect with these non-mass pockets of interest, they’re encouraging further weirdness from whatever niche they are in.

- If you want to sell $900 handmade rifles to obsessive collectors, the easiest way to grow your sales is to grow the market of obsessive rifle collectors. That means that marketers evangelize this particular weirdness to those who might be entranced by it. And then, as the market grows, they go further, pushing the envelope. Making ever lighter and more desired rifles… which means further pushing the edge of what it means to be obsessed. More choices, less mass.

- Just as marketers have actively worked to amplify the feedback loop that makes weird more accepted, individuals are doing the same thing, even when money doesn’t change hands. The reason that people are walking away from mass is not so that they can buy more stuff. Material goods and commerce are not the goal, they are merely a consequence. The goal is connection.

Part three: the gradual and inexorable spread of the Bell curve

- Surely, fishing wasn’t a hobby three thousand years ago. Fishing was work. Somewhere along the way, though, we got rich enough that we could do things that used to be work—and throw back what we caught.

- While wealth permitted us to find expensive, time-consuming hobbies like fishing, we were pushed to whatever hobby we chose in the traditional way, where ‘traditional’ was defined by those in power.

- Media and marketers ensured that most people would do fishing (this new hobby) the same way as everyone else. Field and j Stream and other magazines taught hobbyists the right’ way to do things. Manufacturers encouraged everyone to find a mainstream hobby and buy mainstream supplies will. The local sporting 50ods store sold mass-market items to do the hobby of your choice, but sold only the standard items.

- It’s really quite recently that it took less than ten seconds to find the $3,500 Orvis Special Edition Mitey Mite Bamboo Fly Rod, or to engage with Rocky Ford’s website, where you can find Al Troth’s) Elk Hair Caddis Olive fly for ninety-nine cents. Now, there are as many sorts of fishing techniques as there are fisherman—and plenty of eager supporters for whatever it is you’d like to do.

- Cory Doctorow explains the popularity of file-shared music thusly: “Why did Napster captivate so many of us? Not because it could get us the top-40 tracks that we could hear just by snapping on the radio: it was because 80 percent of the music ever recorded wasn’t available for sale anywhere in the world, and in that 80 percent were all the songs that had ever touched us, all the earworms that had been lodged in our hindbrains, all the stuff that made us smile when we heard it.”

- In other words, it wasn’t the Beatles that made file sharing popular (everyone who loved the Beatles already owned the CDs). No, it was Rung Fu Fighting and the Partridge Family and Sister Sledge that got people hunting for mp3s.

- Tower Records couldn’t satisfy her endless desire for variety and they disappeared.

- Something surprising is happening, though. The defenders of mass and normalcy and compliance are discovering that many of the bell curves that describe our behavior are spreading out

- As soon as merchants discovered they could make a profit by being different, they began to work at being different.

- This trend was compounded by the birth of the industrial age. If you’re a manufacturer, you don’t merely desire specialization. You insist on it. If a new part or a new consultant or a new process is going to improve your productivity, you’ll buy it.

- Tom Harrison runs the DAS group at Omnicom, the second largest ad agency holding company in the world. Here’s the surprising thing: Tom’s group, which contains all the non-advertising parts of the company, all the publicity, promotional and service components, has grown firm 11% to nearly 60% of the company’s revenue in less than fifteen years. That’s right, more than half the revenue at the second-largest ad agency in the world comes from activities that aren’t mass advertising. Game over.

- The Beverly Hillbillies has been replaced by Mad Men. You can be a TV critic if you want, but the marketer in you needs to acknowledge that fifteen times as many people watched Jed Clampett as watch Don Draper.

- Average is for marketers who don’t have enough information to be accurate.

- But mobile is the weirdest of all. That’s because in addition to the silo of me (just me), I add time (I want it now or I want it never) and location (I want it here or I don’t want it). The urgent uptake of mobile devices is further proof that individuals want to connect with their tribe (their Facebook friends, their Foursquare circle, their frequently texted buddies) far more than they want to interact with the more average (more normal) world. Mobile rewards right here, right now, all about me thinking, which is anathema to the factory-based marketer in search of mass.

- If you’ve got only one leg, you can buy a single shoe from Nordstrom’s online. They’ll take care of finding a home for the other half of the pair. An explosion of supply, an explosion of retailers, and a brutal battle for market share have caused “they” to rethink what the market looks like. What they’ve figured out is that mass, the middle of the curve, is nice work if you can get it, but the few customers left in the middle are not enough. There are too many edge cases missing now.

- Ten minutes on Boing Boing reminds me that the world is changing, moving, and getting weirder. It eggs me on. Ten minutes of ESPN puts me to sleep.

- The challenges of the education system are driven by our distance from the problem, not by money. The disconnect is caused by our fervent desire for a return to normal, a normal we actually never had.