Angela Duckworth—2016

Part 1: What Grit is and Why it Matters

Chapter 1 SHOWING UP

- Each year, in their junior year of high school, more than 14,000 applicants begin the admissions process. This pool is winnowed to just 4,000 who succeed in getting the required nomination. Slightly more than half of those applicants—about 2,500—meet West Point s rigorous academic and physical standards, and from that select group just 1,200 are admitted and enrolled.

- And yet, one in five cadets will drop out before graduation

- Why were the highly accomplished so dosed in their pursuits? For most, there was no realistic expectation of ever catching up to their ambitions. In their own eyes, they were never good enough. They were the opposite of complacent. And yet, in a very real sense, they were satisfied being unsatisfied. Each was chasing something of unparalleled interest and importance, and it was the chase—as much as the capture—that was gratifying. Even if some of the things they had to do were boring, or frustrating, or even painful, they wouldn’t dream of giving up. Their passion was enduring.

- In sum, no matter the domain, the highly successful had a kind of ferocious determination that played out in two ways. First, these exemplars were unusually resilient and hardworking. Second, they knew in a very, very deep way what it was they wanted. They not only had determination, they had direction. It was this combination of passion and perseverance that made high achievers special. In a word, they had grit.

- Six months later, I revisited the company, by which time 55 percent of the salespeople were gone. Grit predicted who stayed and who left. Moreover, no other commonly measured personality trait— including extroversion, emotional stability, and conscientiousness was as effective as grit in predicting job retention.

Chapter 2 DISTRACTED BY TALENT

- When they didn’t get something the first time around, they tried again and again, sometimes coming for extra help during their lunch period or during afternoon electives. Their hard work showed in their grades. Apparently aptitude did not guarantee achievement. Talent for math was different from excelling in math class.

- Outliers, Galton concluded, are remarkable in three ways: they demonstrate unusual “ability” in combination with exceptional “zeal” and “the capacity for hard labor.”

- William James wrote an essay on the topic for Science (sign up)

- One way to interpret these stories is that talent is great, but tests of talent stink. There’s certainly an argument to be made that tests of talent—and tests of anything else psychologists study, including grit–are highly imperfect. But another conclusion is that the focus on talent distracts us from something that is at least as important, and that is effort. In the next chapter, I’ll argue that, as much as talent counts, effort counts twice.

Chapter 3 EFFORT COUNTS TWICE

- A few years ago, I read a study of competitive swimmers titled “The Mundanely of Excellence.” The title of the article encapsulates its major conclusion: the most dazzling human achievements are, in fact. The aggregate of countless individual elements, each of which is, in a sense, ordinary.

- Dan Chambliss, the sociologist who completed the study, observed: “Superlative performance is really a confluence of dozens of small skills or activities, each one learned or stumbled upon, which have been carefully drilled into habit and then are fitted together in a synthesized whole. There is nothing extraordinary or superhuman in any one of those actions; only the fact that they are done consistently and correctly, and all together, produce excellence.”

- “Our vanity, our self-love, promotes the cult of the genius, Nietzsche said. “For if we think of genius as something magical, we are not obliged to compare ourselves and find ourselves lacking. … To call someone ‘divine’ means: ‘here there is no need to compete.’ In other words, mythologizing natural talent lets us all off the hook.

- Talent x effort = skill

- Skill x effort = achievement

- Many of us, it seems, quit what we start far too early and far too often. Even more than the effort a gritty person puts in on a single day, what matters is that they wake up the next day, and the next, ready to get on that treadmill and keep going.

Chapter 4 HOW GRITTY ARE YOU?

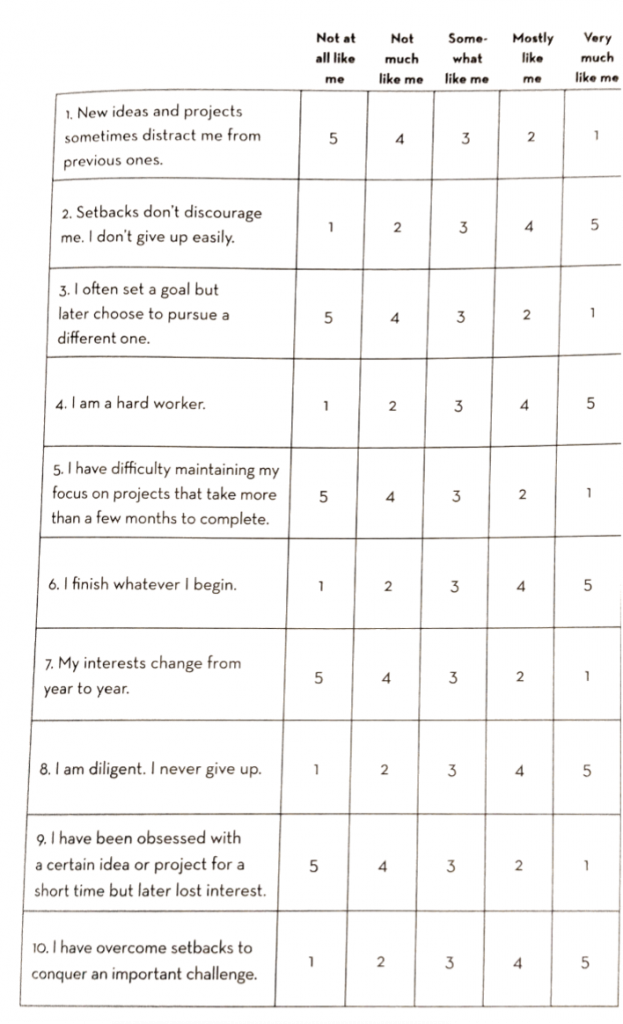

- To calculate your total grit score, add up all the points for the boxes you checked and divide by 10. The maximum score on this scale is 5 (extremely gritty), and the lowest possible score is 1 (not at all gritty). You can use the chart below to see how your scores compare to a large sample of American adults

- Grit has two components: passion and perseverance.

- For your passion score, add up your points for the odd-numbered items and divide by 5. For your perseverance score, add up your points for the even-numbered items and divide by 5.

- Rather than intensity, what comes up again and again in their remarks is the idea of consistency over time.

- This is what my good friend and fellow psychologist Gabriele Oettingen calls “positive fantasizing.” Gabriele’s research suggests that indulging in visions of a positive future without figuring out how to get there, chiefly by considering what obstacles stand in the way has short-term payoffs but long-term costs. In the short-term, you feel pretty great about your aspiration to be a doctor. In the long-term, you live with the disappointment of not having achieved your goal.

- The story goes like this: Buffett turns to his faithful pilot and says that he must have dreams greater than flying Buffett around to where he needs to go. The pilot confesses that, yes, he does. And then Buffett takes him through three steps.

- First, you write down a list of twenty-five career goals.

- Second, you do some soul-searching and circle the five highest priority goals. Just five.

- Third, you take a good hard look at the twenty goals you didn’t circle. These you avoid at all costs. They’re what distract you; they eat away time and energy, taking your eye from the goals that matter more.

- In his role as editor and mentor, Bob advises aspiring cartoonists to submit their drawings in batches of ten, “because in cartooning, as in life, nine out of ten things never work out.”

Chapter 5 GRIT GROWS

- Together, the research reveals the psychological assets that mature paragons of grit have in common. There are four

- They counter each of the buzz-killers listed above, and they tend to develop, over the years, in a particular order.

- First comes interest. Passion begins with intrinsically enjoying what you do.

- Next comes the capacity to practice.

- Third is purpose.

- And, finally hope

- They counter each of the buzz-killers listed above, and they tend to develop, over the years, in a particular order.

- The four psychological assets of interest, practice, purpose, and hope. They are not you have it or you don’t commodities. You can learn to discover, develop, and deepen your interests. You can acquire the habit of discipline. You can cultivate a sense of purpose and meaning. And you can teach yourself to hope.

Part II: Growing Grit from the Inside Out

Chapter 6 INTEREST

- Marc Vetri—Favorite Chef

- Finally, interests thrive when there is a crew of encouraging supporters, including parents, teachers, coaches, and peers. Why are other people so important?

- This is also the conclusion of psychologist Benjamin Bloom, who interviewed 120 people who achieved world-class skills in sports, arts, or science—plus their parents, coaches, and teachers. Among Bloom’s important findings is that the development of skill progresses through three different stages, each lasting several years. Interests are discovered and developed in what Bloom called “the early years.” Encouragement during the early years is crucial because beginners are still figuring out whether they want to commit or cut bait. Accordingly, Bloom and his research team found that the best mentors at this stage were especially warm and supportive: “Perhaps the major quality of these teachers was that they made the initial learning very pleasant and rewarding. Much of the introduction to the field was as playful activity, and the learning at the beginning of this stage was much like a game.

- A degree of autonomy during the early years is also important. Longitudinal studies tracking learners confirm that overbearing parents and teachers erode intrinsic motivation. Kids whose parents let them make their own choices about what they like are more likely to develop interests later identified as a passion.

- For now, what I hope to convey is that experts and beginners have different motivational needs? At the start of an endeavor, we need encouragement and freedom to figure out what we enjoy. We need small wins. We need applause. Yes, we can handle a tincture of criticism and corrective feedback. Yes, we need to practice. But not too much and not too soon. Rush a beginner and you’ll bludgeon their budding interest. It’s very, very hard to get that back once you do.

- For instance, at three, Jeff asked multiple times to sleep in a “big bed.” Jackie explained that eventually he would sleep in a “big bed,” but not yet. She walked into his room the next day and found him, screwdriver in hand, disassembling his crib. Jackie didn’t scold him. Instead, .she sat on the floor and helped. Jeff slept in a “big bed” that night.

- I tried to picture myself in these situations. I tried to picture not freaking out. I tried to imagine doing what Jackie did, which was to notice that her oldest son was blooming into a world-class problem solver, and then merrily nurture that interest.

- www.relentless.com

- If you’d like to follow your passion but haven’t yet fostered one, you must begin at the beginning: discovery.

- What do I like to think about?

- Where does my mind wander?

- What do I really care about?

- What matters most to me?

- How do I enjoy spending my time?

- And, in contrast, what do I find absolutely unbearable?

- If you find it hard to answer these questions, try recalling your teen years, the stage of life at which vocational interests commonly sprouts.

Chapter 7 PRACTICE

- Kaizen is Japanese for resisting the plateau of arrested development. Its literal translation is: “continuous improvement.” A while back, the idea got some traction in American business culture when it was touted as the core principle behind Japan’s spectacularly efficient manufacturing economy. After interviewing dozens and dozens of grit paragons, I can tell you that they all exude kaizen. There are no exceptions. **ASB*

- The really crucial insight of Ericsson’s research, though, is not that experts log more hours of practice. Rather, it’s that experts practice fervently. Unlike most of us, experts are logging thousands upon thousands of hours of what Ericsson calls deliberate practice.

- This is how experts practice:

- First, they set a stretch goal, zeroing in on just one narrow aspect of their overall performance. Rather than focus on what they already do well, experts strive to improve specific weaknesses.

- Then, with undivided attention and great effort, experts strive to reach their stretch goal.

- If, however, you judge practice by what it feels like, you might come to a different conclusion. On average, spellers rated deliberate practice as significantly more effortful, and significantly less enjoyable, than anything else they did to prepare for competition.

- Gritty people do more deliberate practice and experience more flow.

- Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi is talking about how experts feel.

- In other words, deliberate practice is for preparation, and flow for performance.

- Chris Anderson—leader of TED.—She added that id managed to tell a story with absolutely zero suspense.

- That’s right, Grittier kids reported working harder than other kids when doing deliberate practice but, at the same time, said they enjoyed it more than other kids, too. It’s hard to know for sure what to make of this finding. One possibility is that grittier kids spend more time doing deliberate practice, and that, over the years; they develop a taste for hard work as they experience the rewards of their labor. This is the “learn to love the burn” story. Alternatively, it could be that grittier kids enjoy the hard work more, and that gets them to do more of it. This is the “some people enjoy a challenge” story.

- I can’t tell you which of these accounts is accurate, and if I had to guess, I’d say there’s some truth to both. As we’ll learn in chapter 11, there’s solid scientific evidence that the subjective experience of effort—what it feels like to work hard—can and does change when, for example, effort is rewarded in some way. I’ve watched my own daughters learn to enjoy working hard more than they used to, and I can say the same for myself.

- A few years ago, my graduate student Lauren Eskreis-Winkler and I decided to teach kids about deliberate practice. We put together self-guided lessons, complete with cartoons and stories, illustrating key differences between deliberate practice and less effective ways of studying.

- A mountain of research studies, including a few of my own, show that when you have a habit of practicing at the same time and in the same place every day, you hardly have to think about getting started. You just do.

- The book Daily Rituals by Mason Currey describes a day in the life of one hundred sixty-one artists, scientists, and other creators. If you look for a particular rule, like Always drink coffee, or Never drink coffee, or only work in your bedroom, or never work in your bedroom. You won’t find it. But if instead you ask, “What do these creators have in common?” You’ll find the answer right in the title: daily rituals. In their own particular way, all the experts in this book consistently put in hours and hours of solitary deliberate practice. They follow routines. They’re creatures of habit.

- For instance, cartoonist Charles Schulz, who drew almost eighteen thousand Peanuts comic strips in his career, rose at dawn, showered, shaved, and had breakfast with his children. He then drove his kids to school and went to his studio, where he worked through lunch (a ham sandwich and a glass of milk) until his children returned from school. Writer Maya Angelou’s routine was to get up and have coffee with her husband, and then, by seven in the morning, deliver herself to a “tiny mean” hotel room with no distractions until two in the afternoon.

- And then . . . something changes. According to Elena and Deborah, und the time children enter kindergarten, they begin to notice that our mistakes inspire certain reactions in grown-ups. What do we do? We frown. Our cheeks flush a bit. We rush over to our little ones to point out that they’ve done something wrong. And what’s the lesson we’re teaching? Embarrassment. Fear. Shame. Coach Bruce Gemmell says that’s exactly what happens too many of his swimmers: “Between coaches and parents and friends and the media, they’ve learned that failing is bad, so they protect themselves and won’t stick their neck out and give their best effort.”

- “Shame doesn’t help you fix anything.” Deborah told me. So what’s to be done? Elena and Deborah ask teachers to model emotion-free mistake making. They actually instruct teachers to commit an error on purpose and then let students see them say, with a smile, “Oh, gosh, I thought there were five blocks in this pile! Let me count again! One . . . two three . . . four. . . five . . . six! There are six blocks! Great! I learned I need to touch each block as I count!” Whether you can make deliberate practice as ecstatic as flow. I don’t know, but I do think you can try saying to yourself, and to others, “That was hard! It was great!”

Chapter 8 PURPOSE

- At its core, the idea of purpose is the idea that what we do matters to people other than ourselves.

- In sharp contrast, you can see that grittier people are dramatically more motivated than others to seek a meaningful, other-centered life. Higher scores on purpose correlate with higher scores on the Grit Scale.

- My guess is that, if you take a moment to reflect on the times in your life when you’ve really been at your best—when you’ve risen to the challenges before you, finding strength to do what might have seemed impossible—you’ll realize that the goals you achieved were connected in some way, shape, or form to the benefit of other people.

- In the parable of the bricklayers, everyone has the same occupation. But their subjective experience—how they themselves viewed their work—couldn’t be more different.

- It may comfort you to know that it took Michael Baime much longer. Baime is a professor of internal medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. You might think his calling is to heal and to teach. That’s only partly right. Michael’s passion is well-being through mindfulness. It took him years to integrate his personal interest in mindfulness with the other-centered purpose of helping people lead healthier, happier lives. Only when interest and purpose melded did he feel like he was doing what he’d been put on this planet to do.

- The book was by Alan Watts, a British philosopher who wrote about meditation for Western audiences long before it became fashionable.

- Two years later, young people who’d mentioned both self- and other-oriented motives rated their schoolwork as more personally meaningful than classmates who’d named either motive alone.

- Next, you need to observe someone who is purposeful. The purposeful role model could be a family member, a historical figure, a political figure. It doesn’t really matter who it is, and it doesn’t even matter whether that purpose is related to what the child will end up doing. “What matters,” Bill explained, “is that someone demonstrates that it’s possible to accomplish something on behalf of others.”

- But seeing that someone needs our help isn’t enough. Bill hastened to add. Purpose requires a second revelation: “1 personally can make a difference.” This conviction, this intention to take action, he says. Is why it’s so important to have observed a role model enact purpose in their own life. “You have to believe that your efforts will not be in Vain.”

- David Yeager recommends reflecting on how the work you’re already doing can make a positive contribution to society.

- This simple exercise, which took less than a class period to compete, dramatically energized student engagement. Compared to a placebo control exercise, reflecting on purpose led students to double the amount of time they spent studying for an upcoming exam, work harder on tedious math problems when given the option to watch ^entertaining videos instead, and, in math and science classes, bring home better report card grades.

- Amy Wrzesniewski recommends thinking about how, in small hut meaningful ways, you can change your current work to enhance its connection to your core values.

- Amy and her collaborators recently tested this idea at Google. Employees working in positions that don’t immediately bring the word purpose to mind—in sales, marketing, finance, operations, and accounting, for example—were randomly assigned to a job-crafting workshop. They came up with their own ideas for tweaking their daily routines, each employee making a personalized “map” for what would constitute more meaningful and enjoyable work. Six weeks later, managers and coworkers rated the employees who attended this workshop as significantly happier and more effective.

- Finally, Bill Damon recommends finding inspiration in a purposeful role model.

Chapter 9 HOPE

- That our own efforts can improve our future. J have a feeling tomorrow will be better is different from I resolve to make tomorrow better. The hope that gritty people have has nothing to do with luck and everything to do with getting up again.

- Nearly all the dogs who had control over the shocks the previous day learn to leap the barrier.

- This seminal experiment proved for the first time that it isn’t suffering that leads to hopelessness. It’s suffering you think you can’t control.

- Optimists, Marty soon discovered, are just as likely to encounter bad events as pessimists. Where they diverge is in their explanations: optimists habitually search for temporary and specific causes of their suffering, whereas pessimists assume permanent and pervasive causes are to blame.

- Here’s an example from the test Marty and his students developed to distinguish optimists from pessimists: Imagine: You can’t get all the work done that others expect of you. Now imagine one major cause for this event. What leaps to mind? After you read that hypothetical scenario, you write down your response, and then, after you’re offered more scenarios, your responses are rated for how temporary (versus permanent”) and how specific (versus pervasive) they are. If you’re a pessimist, you might say, I screw up everything. Or: I’m a loser. These explanations are all permanent; there’s not much you do to change them.

- You’re an optimist, you might say, I mismanaged my time. Or: J didn’t work efficiently because of distractions. These explanations are all temporary and specific; their “fixability” motivates you to start clearing them away as problems.

- How do grit paragons think about setbacks? Overwhelmingly, I’ve found that they explain events optimistically. Journalist Hester Lacey finds the same striking pattern in her interviews with remarkably creative people. “What has been your greatest disappointment?” she asks each of them. Whether they’re artists or entrepreneurs or community activists, their response is nearly identical. “Well, I don’t really think in terms of disappointment. I tend to think that everything that happens is something I can learn from. I tend to think, ‘Well okay, that didn’t go so well, but I guess I will just carry on.

- When you keep searching for ways to change your situation for the better, you stand a chance of finding them. When you stop searching, assuming they can’t be found, you guarantee they won’t.

- Here are four statements Carol uses to assess a person’s theory of intelligence. Read them now and consider how much you agree or disagree with each:

- Your intelligence is something very basic about you that you can’t change very much.

- You can learn new things, but you can’t really change how intelligent you are.

- No matter how much intelligence you have, you can always change it quite a bit.

- You can always substantially change how intelligent you are.

- If you found yourself nodding affirmatively to the first two statements but shaking your head in disagreement with the last two, then Carol would say you have more of a fixed mindset. If you had the opposite reaction, then Carol would say you tend toward a growth mindset.

- Growth mindset and grit go together.

- When you ask Carol where our mindsets come from, she’ll point to people’s personal histories of success and failure and how the people around them, particularly those in a position of authority, have responded to these outcomes.

| Undermines Growth Mindset and Grit | Promotes Growth Mindset and Grit |

| “You’re a natural! I love that.” | “You’re a learner! I love that.” |

| “Well, at least you tried!” | “That didn’t work. Let’s talk about now you approached it and what might work better.” |

| “Great job! You’re so talented!” | “Great job! What’s one thing that could have been even better?” |

| “Maybe this just isn’t your strength. Don’t worry—you have other things to contribute” | Have high standards. I’m holding you to them because I know we can reach them together.’ |

- Similarly, Carol and her collaborators are finding that children develop more of a fixed mindset when their parents react to mistakes as though they’re harmful and problematic. This is true even when these parents say they have a growth mindset. Our children are watching us, and they’re imitating what we do.

- “We’ve actually tracked senior leaders here at Vanguard and asked why some did better in the long run than others. I used to use the word ‘complacency’ to describe the ones who didn’t work out, but the more I reflect on it, the more I realize that’s not quite it. It’s really a belief that ‘I can’t learn anymore. I am what I am. This is how I do things.’” And what about executives who ultimately excelled? “The people who have continued to be successful here have stayed on a growth trajectory. They just keep surprising you with how much I they’re growing.

- If you experience adversity—something pretty potent—that you overcome on your own during your youth, you develop a different way of dealing with adversity later on.

- “That’s right. Just telling somebody they can overcome adversity isn’t enough. For the rewiring to happen, you have to activate the control circuitry at the same time as those low-level inhibitory areas. That happens when you experience mastery at the same time as adversity.”

- Growth mindset Optimistic Self-talk Perseverance over adversity

- My recommendation for teaching yourself hope is to take each step in the sequence above and ask. What can I do to boost this one? My first suggestion in that regard is to update your beliefs about intelligence and talent. ‘When Carol and her collaborators try to convince people that intelligence or any other talent, can improve with effort, she starts by explaining the brain.

- My next suggestion is to practice optimistic self-talk. The link between cognitive behavioral therapy and learned helplessness led to the development of “resilience training.” In essence. This interactive curriculum is a preventative dose of cognitive behavioral therapy In one study, children who completed this training showed lower levels of , of pessimism and developed fewer symptoms of depression over the next two years.’

- The point is that you can, in fact, modify your self-talk, and you can learn to not let it interfere with you moving toward your goals.

Part III Growing Grit from Outside In

Chapter 10 PARENTING FOR GRIT

- First and foremost, there’s no either/or trade-off between supportive parenting and demanding parenting. It’s a common misunderstanding to think of “tough love” as a carefully struck balance between affection and respect on the one hand, and firmly enforced expectations on the other. In actuality, there’s no reason you can’t do both. Very clearly this is exactly what the parents of Steve Young and Francesca Martinez did. The Young’s were tough, but they were also loving. The Martinez’s were loving, but they were also tough. Both families were child-centered” in the sense that they clearly put their children’s interests first, but neither family felt that children were always the better judge of what to do, how hard to work, and when to give up on things.

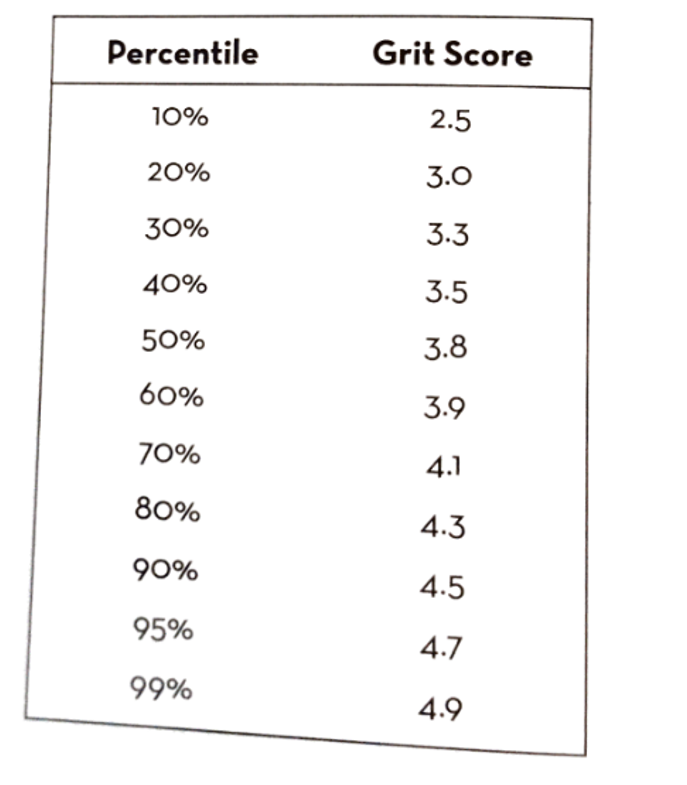

- Below is a figure representing how many psychologists now categorize parenting styles. Instead of one continuum, there are two. In the upper right-hand quadrant are parents who are both demanding and supportive. The technical term is “authoritative parenting,” which, unfortunately is easily confused with “authoritarian parenting.” To avoid such confusion, I’ll refer to authoritative parenting as wise parenting, because parents in this quadrant are accurate judges of the psychological needs of their children. They appreciate that children need love, limits, and latitude to reach their full potential. Their authority is based on knowledge and wisdom, rather than power.

- In the other quadrants are three other common parenting styles, including the undemanding, unsupportive approach to raising children exemplified by neglectful parents. Neglectful parenting creates an especially toxic emotional climate, but I won’t say much more about it here because it’s not even a plausible contender for how parents of the gritty raise their children.

- Authoritarian parents are demanding and unsupportive, exactly the approach John Watson advocated for strengthening character in children. Permissive parents, by contrast, are supportive and undemanding.

- When psychologist Larry Steinberg delivered his 2001 presidential address to the Society for Research on Adolescence, he proposed a moratorium on further research on parenting styles because, as he saw it, there was so much evidence for the benefits of supportive and demanding parenting that scientists could profitably move on to thornier research questions. Indeed, over the past forty years, study after carefully designed study has found that the children of psychologically wise parents fare better than children raised in any other kind of household.

- In one of Larry’s studies, for example, about ten thousand American teenagers completed questionnaires about their parents’ behavior regardless of gender, ethnicity, social class, or parents’ marital status. Teens with warm, respectful, and demanding parents earned higher grades in school, were more self-reliant, suffered from less anxiety and depression, and were less likely to engage in delinquent behavior. The same pattern replicates in nearly every nation that’s been studied and at every stage of child development. Longitudinal research indicates that the benefits are measurable across a decade or more.

- One of the major discoveries of parenting research is that what matters more than the messages parents aim to deliver are the messages their children receive. What may appear to be textbook authoritarian parenting—a no television policy for example, or a prohibition against swearing—may IT may not be coercive. Alternatively, what may seem permissive—say. Letting a child drop out of high school—may simply reflect differences in the rules parents’ value as important. In other words, don’t pass judgment on that parent lecturing their child in the supermarket cereal aisle. In most cases, you don’t have enough context to understand how the child interprets the exchange, and, at the end of the day, it’s the child’s experience that really matters.

- Are you a psychologically wise parent? Use the parenting assessment on the next page, developed by psychologist and parenting expert Nancy Darling, as a checklist to find out. How many of these statements would your child affirm without hesitation?

- You’ll notice that some of the items are italicized. These are “reverse-coded” items, meaning that if your child agrees with them, you may be less psychologically wise than you think.

- Supportive: Warm

- I can count on my parents to help me out if I have a problem.

- My parents spend time just talking to me.

- My parents and I do things that are fun together.

- My parents don’t really like me to tell them my troubles.

- My parents hardly ever praise me for doing well.

- Supportive: Respectful

- My parents believe I have a right to my own point of view.

- My parents tell me that their ideas are correct and that I shouldn’t question them.

- My parents respect my privacy.

- My parents give me a lot of freedom.

- My parents make most of the decisions about what I can do.

- Demanding

- My parents really expect me to follow family rules.

- My parents really let me get away with things.

- My parents point out ways I could do better.

- When do something wrong, my parents don’t punish me.

- My parents expect me to do my best even when it’s hard.

- Growing up with support, respect, and high standards confers a lot of benefits, one of which is especially relevant to grit—in other words, wise parenting encourages children to emulate their parents.

- Benjamin Bloom and his team noted the same pattern in their studies of world-class performers. Almost without exception, the supportive and demanding parents in Bloom’s study were “models of the work ethic in that they were regarded as hard workers, they did their best in whatever they tried, they believed that work should come before play, and that one should work toward distant goals.” Further, “most of the parents found it natural to encourage their children to participate in their favored activities.” Indeed, one of Bloom’s summary conclusions was that “parents’ own interests somehow get communicated to the child. . . . We found over and over again that the parents of the pianists would send their child to the tennis lessons but they would take their child to the piano lessons. And we found just the opposite for the tennis homes.’

- If you want to bring forth grit in your child, first ask how much passion and perseverance you have for your own life goals. Then ask yourself how likely it is that your approach to parenting encourage your child to emulate you. If the answer to the first question is “a great deal,” and your answer to the second is “very likely,” you’re already parenting for grit.

- “This pattern kept on repeating itself,” Tobi said. “Jurgen somehow knew the extent of my comfort zone and manufactured situations which were slightly outside it. I overcame them through trial and error, through doing. … I succeeded.”

- He found that teachers who are demanding—whose students say of them, “My teacher accepts nothing less than our best effort,” and “Students this class behave the way my teacher wants them to”—produce measurable year-to-year gains in the academic skills of their students Teachers who are supportive and respectful—whose students say, “my teacher seems to know if something is bothering me,” and “My teach( wants us to share our thoughts”—enhance students’ happiness, voluntary effort in class, and college aspirations.

- Recently, psychologists David Yeager and Geoff Cohen ran an experiment to see what effect the message of high expectations in conjunction with unflagging support had on students. They asked seventh-grade teachers to provide written feedback on student essays. Including suggestions for improvement and any words of encouragement they would normally give. Per usual, teachers filled the margins of the students’ essays with comments.

- Next, teachers passed all of the marked-up essays to researchers, who randomly sorted them into two piles. On half of the essays. Researchers affixed a Post-it note that read: I’m giving you these comments so that you’ll have feedback on your paper. This was the placebo control condition.

- On the other half of the essays, researchers affixed a Post-it note that read: I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations and I know that you can reach them. This was the wise feedback condition.

- So that teachers would not see which student received which note. In fact, students would not notice that some of their classmates had received a different note than they had, researchers placed each essay in a folder for teachers to hand back to the students during class. Students were then given the option to revise their essays the following week.

- When the essays were collected, David discovered that about 40 percent of the students who’d received the placebo control Post-it note decided to turn in a revised essay, compared to about twice that number—80 percent of the students—who’d received the Post-it note communicating wise feedback.

- In a replication study with a different sample, students who received the wise feedback Post-it—“I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations and I know that you can reach them”—made twice as many edits to their essays as students in the placebo control condition.

- Most certainly. Post-it notes are no substitute for the daily gestures. Comments, and actions that communicate warmth, respect, and high expectations. But these experiments do illuminate the powerful motivating effect that a simple message can have.

Chapter 11 THE PLAYING FIELDS OF GRIT

- Do I think every moment of a child’s day should be scripted? Not at all. But I do think kids thrive when they spend at least some part of their week doing hard things that interest them.

- For starters, a few researchers have equipped kids with beepers so that, throughout the day, they can be prompted to report on what they’re doing and how they feel at that very moment. When kids are in class, they report feeling challenged—but especially unmotivated. Hanging out with friends, in contrast, is not very challenging but super fun. And what about extracurricular activities? When kids are playing sports or music or rehearsing for the school play, they’re both challenged and having fun. There’s no other experience in the lives of young people that reliably provides this combination of challenge and intrinsic motivation.

- Even more convincing evidence for the benefits of long-term extracurricular activities comes from a study conducted by psychologist Margo Gardner. Margo and her collaborators at Columbia University followed eleven thousand American teenagers until they were twenty-six years old to see what effect, if any, participating in high school extracurricular for two years, as opposed to just one, might have on success in adulthood.

- Here’s what Margo found: kids who spend more than a year in extracurricular are significantly more likely to graduate from college and, as young adults, to volunteer in their communities. The hours per week kids devote to extracurricular also predict having a job (as opposed to being unemployed as a young adult) and earning more money, but only for kids who participate in activities for two years rather than one.

- But when all the data were finally in, Willingham was unequivocal and emphatic about what he’d learned. One horse did win, and by a long stretch: follow-through. This is how Willingham and his team put a number on it: “The follow-through rating involved evidence of purposeful, continuous commitment to certain types of activities (in high school) versus sporadic efforts in diverse areas.”

- Students who earned a top follow-through rating participated in two different high school extracurricular activities for several years each and, in both of those activities, advanced significantly in some way (e.g., becoming editor of the newspaper, winning MVP for the volleyball team, winning a prize for artwork). As an example, Willingham described a student who was “on his school newspaper staff for three years and became managing editor, and was on the track team for three years and ended up winning an important meet.”

- In contrast, students who hadn’t participated in a single multiyear activity earned the lowest possible follow-through rating. Some students in this category didn’t participate in any activities at all in high school. But many, many others were simply itinerant, joining a club or team one year but then, the following year, moving on to something entirely different.

- The predictive power of follow-through was striking: After controlling for high school grades and SAT scores, follow-through in high school extracurriculars predicted graduating from college with academic honors better than any variable. Likewise, follow-through was the single best predictor of holding an appointed or elected leadership position in young adulthood. And, finally, better than any of the more than one hundred personal characteristics Willingham had measured. Follow-through predicted notable accomplishments for a young adult in all domains, from the arts and writing to entrepreneurism and community service.

- “Notably the particular pursuits to which students had devoted themselves in high school didn’t matter—whether it was tennis, student government, or debate team. The key was that students had signed up for something, signed up again the following year, and during that time had made some kind of progress.

- Directions: Please list activities in which you spent a significant amount of time outside of class. They can be any kind of pursuit, including sports, extracurricular activities, volunteer activities, research/academic activities, paid work, or hobbies. If you do not have a second or third activity, please leave those rows blank:

| Activity | Grade level of participation 9-10-11-12 | Achievements, awards, leadership positions, if any |

- In a separate study, we applied the same Grit Grid scoring system to the college extracurriculars of novice teachers. The results were strikingly similar. Teachers who, in college, had demonstrated productive follow-through in a few extracurricular commitments were more likely to stay in teaching and, furthermore, were more effective in producing academic gains in their students. In contrast, persistence and effectiveness in teaching had absolutely no measurable relationship] with teachers’ SAT scores, their college GPAs, or interviewer ratings of their leadership potential.

- Psychologist Robert Eisenberger at the University of Houston is the leading authority on this topic. He’s run dozens of studies in which rats are randomly assigned to do something hard—like press a lever twenty times to get a single pellet of rat chow—or something easy, like press that lever two times to get the same reward. Afterward, Bob gives all the rats a different difficult task. In experiment after experiment, he’s found the same results: Compared to rats in the “easy condition,” rats who were previously required to work hard for rewards subsequently demonstrate more vigor and endurance on the second task.

- In our family we live by the Hard Thing Rule. It has three parts. The first is that everyone—including Mom and Dad—has to do a hard thing. A hard thing is something that requires daily deliberate practice. I’ve told my kids that psychological research is my hard thing, but I also practice yoga. Dad tries to get better and better at being a real estate developer; he does the same with running. My oldest daughter, Amanda, has chosen playing the piano as her hard thing. She did ballet for years, but later quit. So did Lucy.

- This brings me to the second part of the Hard Thing Rule: You can quit. But you can’t quit until the season is over, the tuition payment is up, or some other “natural” stopping point has arrived. You must, at least for the interval to which you’ve committed yourself, finish whatever you begin. In other words, you can’t quit on a day when your teacher yells at you, or you lose a race, or you have to miss a sleepover because of a recital the next morning. You can’t quit on a bad day

- Nobody picks it for you because, after all, it would make no sense to do a hard thing you’re not even vaguely interested in.

- Next year, Amanda will be in high school. Her sister will follow the year after. At that point, the Hard Thing Rule will change. A fourth requirement will be added: each girl must commit to at least one activity, either something new or the piano and viola they’ve already started for at least two years.

Chapter 12 A CULTURE OF GRIT

- The drive to fit in—to conform to the group—is powerful indeed. Some of the most important psychology experiments in history have demonstrated how quickly, and usually without conscious awareness. The individual falls in line with a group that is acting or thinking a different way.

- “So it seems to me,” Dan concluded, “that there’s a hard way to get grit and an easy way. The hard way is to do it by yourself. The easy way is to use conformity—the basic human drive to fit in—because if you’re around a lot of people who are gritty, you’re going to act grittier.”

- Anson sees the Beep Test as a twofold test of character. “I give a little speech beforehand about what this is going to prove to me,” he told me. “If you do well, either you have self-discipline because you’ve trained all summer, or you have the mental toughness to handle the pain that most people can’t. Ideally, of course, you have both.” Just before the first beep, Anson announces, “ladies, this is a test of your mentality. Go!’’

- Over the years, Anson has developed a list of twelve carefully worded core values that define what it means to be a UNC Tar Heel.

- No whining. No complaining. Be early.

- After most of the team has moved on to lunch, one of the Seahawks asks me what he should do about his little brother. His brother’s very smart, he says, but at some point, his grades started slipping. As an incentive, he bought a brand-new Xbox video-game console and placed it, still in its packaging, in his brother’s bedroom. The deal was that, when the report card comes home with A’s, he gets to unwrap the game. At first, this scheme seemed to be working, but then his brother hit a slump. “Should I just give him the Xbox?” he asks me.

- Before I can answer, another player says, “Well, man, maybe he’s just not capable of A’s.” I shake my head. “From what I’ve been told, your brother is plenty smart enough to bring home As. He was doing it before.”

- The player agrees. “He’s a smart kid. Trust me, he’s a smart kid.” I’m still thinking when Pete jumps up and says, with genuine excitement: “First of all, there is absolutely no way you give that game to your brother. You got him motivated. Okay, that’s a start. That’s a beginning. Now what? He needs some coaching He needs someone to explain what he needs to do, specifically, to get back to good grades! He needs a plan! He needs your help in figuring out those next steps.

Chapter 13 CONCLUSION

- Let me close with a few final thoughts. The first is that you can grow your grit.

- I see two ways to do so. On your own, you can grow your grit “from the inside out”: You can cultivate your interests. You can develop a habit of daily challenge-exceeding-skill practice. You can connect your work to a purpose beyond yourself. And you can learn to hope when all seems lost.

- You can also grow your grit “from the outside in.” Parents, coaches. Teachers, bosses, mentors, friends—developing your personal grit depends critically on other people.