Great At Work – How Top Performers Do Less, Work Better, and Achieve More

Morten T. Hansen

Chapter 1: The Secrets to Great Performance

How often have you heard phrases like “She’s a natural at sales” or “He’s a brilliant engineer”? One influential book titled The War for Talent argues that a company’s ability to recruit and retain talent determines its success. The popular StrengthsFinder approach advocates that you find a job that taps into your natural strengths, and then focus on developing those further. These talent-based explanations are deeply embedded in our perceptions of what makes for success. But are they right?

Some work experts take issue with the talent view. They argue that an individual’s sustained effort is just as critical or even more so in determining success. In one variant of this “work hard” paradigm, people perform because they have grit, persevering against obstacles over the long haul. In another, people maximize efforts by doing more: they take on many assignments and are busy running to lots of meetings. That’s the approach I subscribed to while at BCG, where I put in long hours in an effort to accomplish more. Many people believe that working harder is a key to success.

I decided to take a different approach, exploring whether the way some people work–their specific work practices as opposed to the sheer amount of effort they exert–accounts for greatness at work. That led me to explore the idea of “working smart,” whereby people seek to maximize output per hour of work. The phrase “work smarter, not harder” has been thrown around so much that it has become a cliche. Who wants to “work dumb”? But many people do in fact work dumb because they don’t know exactly how to work smart. And I don’t blame them, because it’s hard to obtain solid guidance.

In the end, we discovered that seven “work smart” practices seemed to explain a substantial portion of performance. (It always seems to be seven, doesn’t it?) When you work smart, you select a tiny set of priorities and make huge efforts in those chosen areas (what I call the work scope practice). You focus on creating value, not just reaching preset goals (targeting). You eschew mindless repetition in favor of better skills practice (quality learning). You seek roles that match your passion with a strong sense of purpose (inner motivation). You shrewdly deploy influence tactics to gain the support of others (advocacy). You cut back on wasteful team meetings, and make sure that the ones you do attend spark vigorous debate (rigorous teamwork). You carefully pick which cross-unit projects to get involved in, and say no to less productive ones (disciplined collaboration). This is a pretty comprehensive list. The first four relate to mastering your own work, while the remaining three concern mastering working with others.;

Not What We Expected

Once they had focused on a few priorities, they obsessed over those tasks to produce quality work. That extreme dedication to their priorities created extraordinary results. Top performers did less and more: less volume of activities, more concentrated effort. This insight overturns much conventional thinking about focusing that urges you to choose a few tasks to prioritize. Choice is only half of the equation–you also need to obsess. This finding led us to reformulate the “work scope” practice and call it “do less, then obsess.”

Our results overturned yet another typical view, the idea that collaboration is necessarily good and that more is better. Experts advise us to tear down “silos” in organizations, collaborate more, build large professional networks, and use lots of high-tech communication tools to get work done. Well, my research shows that convention to be dead wrong. Top performers collaborate less. They carefully choose which projects and tasks to join and which to flee, and they channel their efforts and resources to excel in the few chosen ones. They discipline their collaboration.

Testing the New Theory

In fact, they accounted for a whopping 66 percent of the variation in performance among the 5,000 people in our dataset.

Chapter 2: Do Less, Then Obsess

One leader and his team Achieved the extraordinary, while the other team perished in the polar night. Why? What made the difference? Over the years, authors have offered several explanations. In our book Great by Choice, Jim Collins and I attributed Amundsen’s success to better pacing and self-control. Others have pointed to good planning or even luck to explain Amundsen’s success and Scott’s failure.

However, many accounts neglect one critical part of the dramatic South Pole race: the scope of the expeditions. One team fielded superior resources: a grander ship, 187 feet vs. 128 ft; a bigger budget, £40,000 vs. £20,000; and a larger crew, 65 vs. 19 men. How could one win against such a mighty foe? It was an unfair race. Except for one thing.

Amundsen’s Team was the one with the narrow scope. Captain Scott commanded three times the men and twice the budget. He used five forms of transportation: dogs, motor sledges, Siberian ponies, skis, and man-hauling. If one failed, he had backups. Amundsen relied on only one form of transportation: dogs. Had they failed, his quest would have ended. But Amundsen’s dogs didn’t fail. They performed. Why?

It wasn’t just his choice to use dogs–Scott took dogs, too. Amundsen succeeded to a large degree because he concentrated only on dogs and eschewed backup options. During his three-year trip through the Northwest Passage, he had spent two winters apprenticing with Inuits who had mastered dog sledging. Running a span of dogs is hard. They are unruly animals and sometimes drop down in the snow and refuse to work. Amundsen learned from the natives how to urge the dogs to run, how to drive sledges, and how to pace himself.

Amundsen also obsessed over obtaining superior dogs. His research suggested that Greenlander dogs handled polar travel better than Siberian huskies. Greenland dogs were bigger and stronger, and with their longer legs they could better traverse the snowdrift across the ice barrier and the polar plateau. Amundsen traveled to Copenhagen to enlist the help of the Danish inspector of North Greenland. “As far as dogs are concerned, it is absolutely essential that I obtain the very best it is conceivable to obtain,” he wrote in a follow-up letter. “Naturally, I am fully aware that as a result, the price must be higher than that normally paid.” He sought out expert dog runners to join his team, several more skilled than he. When the star dog driver Sverre Hassel declined, Amundsen didn’t look for the next best but kept pursuing Hassel. According to historian Roland Huntford, “Amundsen now exerted all his charm and force of character to coax Hassel, after all, to sail with him. In the end, Hassel, worn down by his persistence, agreed.”

Hurt by Complexity

Toggling cases slowed them down. Other studies have shown that switching between tasks can decrease your productivity by as much as 40 percent.” … If we select just a few items and obsess to excel in those, we can perform at our best. What does obsession look like in the workplace?

Massage the Octopus

For the past fifty years, ninety-one-year-old Jiro Ono has operated the sushi restaurant Sukiyabashi Jiro, tucked under the underpass of a subway station in Tokyo. (Margin Note – Jiro!)

The worst-performing group consisted of people who took on many priorities, but then didn’t put in much effort. They were the “accept more, then coast” employees and ranked in the bottom 11th percentile. Ouch.

The second-lowest-performing group, at the 53rd percentile, scored very high on “extremely good at focusing on key priorities,” but low on effort. We named this group, “Do less, no stress.” These were the people in our study who selected a few priorities, but then failed to obsess. Just choosing to focus, as work-productivity experts would have you do, does not lead to best performance.

The second best-performing group, at the 54th percentile, consisted of employees who accepted many responsibilities and then became overwhelmed as they worked hard to complete them. They scored low on focus, and high on effort. We called this the “do more, then stress” group. Susan Bishop, the executive recruiter, landed in this category: she took on too many responsibilities (receiving a poor 3 out of 7 “do less” score), yet put in a huge amount of effort (a top score of 7). Notice that this group performed at roughly the same level as the “do less, no stress” group. That is, if you violate either the “do less” or the “obsess” criterion, your performance will remain about average–slightly above the 50th percentile.

Finally, we have the Jiros and then Amundsens of the world, those who excelled at choosing a few priorities and channeling their obsessionlike effort to excel in those areas.

The people in our study cited three main reasons for failing to focus: broad scope of work activities (including having too many meetings and too many work items), temptations (including distractions imposed by others and temptations created by oneself), and pesky, “do-more” bosses (who lack direction and set too many priorities). These three main reasons correspond in turn to three tactics we can deploy to do less and obsess. Let’s look at how to narrow your scope.

You can apply Occam’s Razor to simplify and narrow the scope of your work.

Tie Yourself to the Mast

Twenty-one percent of employees in our study regarded temptations and distractions as key impediments to focusing. The second tactic for focusing and obsessing, then, is to seal yourself off from those distractions. I did that while writing this book. Knowing how hard writing is for me, and how tempted I am to procrastinate, I bought a laptop and got rid of the internet browser, email, and the instant messaging app–everything except for Microsoft Word. I carried this barren computer to Starbucks for two-hour intervals. Day after day, I sat there with my dark-roast tall coffee (black, no sugar). I felt a terrible urge to check my email–but I couldn’t. So I kept writing. Before long, I had completed a manuscript.

How to Say “No” to Your Boss

“Not if you want excellent work,” James replied. “The merger project requires all my attention for the next three weeks, and there is no slack in the schedule. The key is to deliver the best quality, so we will need some more people on the merger project if you want me to help with the sales bid.”

Make clear to your boss that you’re not trying to slack off. You’re prioritizing because you want to dedicate all your effort to excelling in a few key areas.

Chapter 3: Redesign Your Work

A few years earlier, while coaching his son’s Little League team, Green had discovered some instructional videos on YouTube that included annotated drawings illustrating the basics of the game. “You could actually see what each position did,” he enthused in one of our interviews with him for our study. Green decided to show the YouTube video clips to his son’s team and create some videos of his own. The boys studied the videos at home once a week and came to the baseball diamond prepared. “I realized that I didn’t have to repeat myself over and over to each kid,” Green recalled. “I also realized that the players could go back and review the videos periodically on their own.”

As soon as he learned that his school was on the list, Green gathered the teachers in a conference room. He jumped on the Internet and showed them his baseball videos. “Let’s record our lectures and put the videos on the Internet to be accessed by students,” he suggested. “How crazy would it be to try something like this at Clintondale?” Students would view the lessons at home and on the bus and then do “homework” in the classroom. The teacher would no longer be a lecturer, but rather a coach. They would flip the process, classroom at home, homework at school.

To Perform Better, Redesign What You Do

Instead Green redesigned the work itself, changing the way teaching was done. He found a way to achieve greater impact with the same effort–in other words, to work smarter.

Redesign for Value

Delving back into our data, we found that fruitful redesigns all shared one thing in common: value. A good redesign delivers more value for the same amount of work done. That begs the question: what is value, exactly?

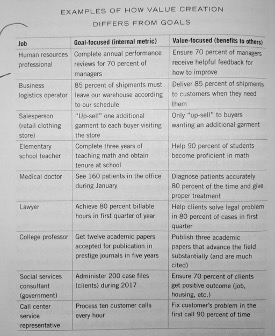

As our study suggested, we should evaluate the value of our work by measuring how much others benefit from it. That’s an outside-in view, because it directs attention to the benefits our work brings to others. The inside-out view, by contrast, measures work according to whether we have completed our tasks and goals, regardless of whether they produce any benefits.

Don’t Pursue Goals, But Value

The value of a person’s work = benefits to others x quality x efficiency. Putting it all together, we get a more precise view of value: to produce great value at work is to create output that benefits others tremendously and that is done efficiently and with high quality.

With our value equation in place, we’re now better equipped to address the question we raised at the end of the last chapter. If you want to perform at your best, you need to home in on a few key tasks and channel your efforts to perfect them – the “do less, then obsess” principle. But which activities warrant such focus? If you’re going to focus on a tiny set of activities, they better be the right ones. The answer is to redesign work so as to focus on activities that maximize value, as defined in the above value equation. But how exactly do you do that?

Hunt for Pain Points

What pain points can you spot in your workplace? What do people complain about again and again and again? What gets people confused and frustrated and saying “this sucks”? Where does work tend to get bogged down?

Hunting for pain points is counter-intuitive. When we hear people complain, we tend to dismiss them as whiners. Carmen might have grown to resent all those angry insurance agents. Instead, she went beyond her job specification and worked with software coders to create a better setup. As annoying as complainers might sometimes seem, they do us all a service–they identify the pain, for free!

Key Insights – Redesign Your Work

Key Points

- Our statistical analysis of 5,000 managers and employees demonstrates that those who redesigned their work performed significantly better than those who didn’t.

- Explorer 5 ways to redesign work to create value:

- Less fluff: eliminate existing activities of little value

- More right stuff: increase existing activities of high value

- More “Gee, whiz”: create new activities of high value

- Five star rating: improve quality of existing stuff

- Faster, cheaper: do existing activities more efficiently

Chapter 4: Don’t Just Learn, Loop

I respectfully disagree. Deliberate practice translates far better to the workplace then we might think. But there’s a crucial twist. As we discovered in our research, we can’t just take deliberate practice and “copy and paste” it into the workplace. Instead, we must implement a different version – what I call the learning loop. Employees and managers who improve their skills at work follow several tactics that you don’t find in traditional deliberate practice as deployed in the Performing Arts and sports. They discard isolated practice in favor of learning as they work, using actual work activities such as meetings or presentations as learning opportunities. They also spend just a few minutes each day learning, eschewing the three- to four-hour practice sessions common among musicians and athletes. They also rely on informal, rapid feedback from peers, direct reports, and bosses, and not just coaches. And they take steps to measure the “softer” skills that permeate the workplace. As I will detail, people embracing the learning loop follow six highly effective tactics geared specifically to the workplace.

Looping Tactic #1: Carve Out the 15

Can you really hammer out significant progress by devoting just 15 minutes a day? Yes, so long as you stick to the Power of One: Pick one and only one skill at a time to develop. It’s hard to master a skill if you’re also working on 10 others. Ask yourself, which skill would, if improved, lift your performance the most? Choose that one to work on first, and devote fifteen minutes a day–yes, just fifteen.

Looping Tactic #2: Chunk It

To start improving a skill, effective Learners in the workplace break it into manageable chunks, what I call micro-behaviors. A micro-behavior is a small concrete action you take on a daily basis to improve a skill. The action shouldn’t take more than 15 minutes to perform and review, and it should have a clear impact on skill development.

Brittany broke her overall skill area of getting the team to generate ideas into the micro-behaviors of “asking a question that gets people to propose an idea,” “asking a follow-up question that generates more detail,” and “securing follow-up commitment from team members,” among others.

In a leadership development program I have been running for the Scandinavian media company Schibsted, we tackled a tough but common challenge: getting managers to embrace and implement the company’s leadership competencies on a daily basis. Many companies articulate such competencies, yet people often fail to embrace them. Schibsted adopted twelve leadership competencies, including “ cultivate speed and flexibility,” “execute and follow through to results, no excuses,” and “insist on fact-based decisions.” Although managers understood these formulations, they needed to translate these into daily, concrete actions. To help them do so, we crafted ten micro-behaviors for each competence. Managers completed 360-assessments to identify their specific areas of development. They then used the “power of one” to pick one and only one competence at a time. To help them, we developed a smartphone “app” that each week sent them to micro behaviors they could use while working.

Chapter 5: P-Squared (Passion And Purpose)

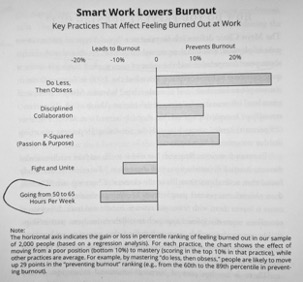

Purpose and passion are not the same. Passion is “do what you love,” while purpose is “do what contributes.” Purpose asks, “What can I give the world?” Passion asks, “What can the world give me?”…high levels of both passion and purpose–”P-squared,” as I call it–was the second most important one, predicting a boost in a person’s percentile rank of 18 points compared with a similar person who had neither passion nor purpose.

What’s the real magic of P-squared? It provides people with more energy that they channel into their work. Not more hours as in the “work harder” paradigm, but more energy per hour of work. That’s working smart.

Climb the Purpose Pyramid

Another way to maximize your passion-purpose match is to infuse your present job with more purposeful activities. Let’s remember the key difference between passion and purpose. Passion is doing what you love; purpose is doing what contributes.

Chapter 6: Forceful Champions

Convincing Other People

As Telford’s story demonstrates, getting our work done hingest on our ability to gain support from others, including bosses, subordinates, peers, colleagues in other departments, and partners. These individuals control resources we need–information, expertise, money, staff, and political cover.

Analyzing our data, we found that top performers mastered working with others in three areas: advocacy, teamwork, and collaboration. In this chapter, we explore the vital task of advocating for your goals so as to win other people’s support.

Champion Forcefully

Many of us believe that we need to appeal to people’s rational minds to gain their support for our projects and goals. Just explain the merits of the case using logic and data, and others will rise up in support.

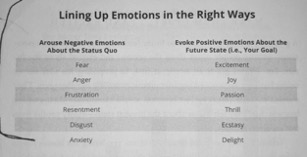

When we analyzed our case studies, I was struck by how the best performers went beyond rational arguments and adopted various tactics to advocate for their projects. I discovered that the best advocates–what I call forceful champions–effectively pursued their goals at work by mastering two skills to gain the support of other people. They inspired others by evoking emotions, and they circumvented resistance by deploying “smart grit.”

First, the forceful champions in our study Inspired people appealing to their emotions as well as their rational minds to garner support. As Maya Angelou reminds us, people never forget how you make them feel. Her point is echoed by academic theory is that show how leaders gain support by making others feel excited about their vision, goals, and plans. While leadership theory often emphasizes the role of personal charisma in eliciting such emotions, you don’t need to be charismatic to inspire others. The forceful champions in our study used a number of practical techniques to start emotions that everyone can adopt regardless of their job titles.

The second skill that forceful champions used in our study, smart grit, and Tails persevering in the face of difficulty and deploying tailored tactics to overcome opposition to their effort.

Psychologists such as University of Pennsylvania professor Angela Duckworth have demonstrated that grit–which she defines as perseverance and passion for long-term goals–distinguished successful people from others. In pursuing their goals, forceful champions in our study applied such grit to overcome opposition. But rather than simply plod forward, mustering endless amounts of energy and verbiage to overcome obstacles, they also deployed smart tactics to address their colleagues’ specific concerns. Like Ian Telford, they identified and read their opponents’ intentions and took steps, such as compromising or co-opting, to convince them to support their cause.

Make Them Upset . . . And Excited

A great way to inspire others is to foster both negative and positive emotions, getting people upset about the present and excited about the future. Ian Telford got it all wrong at first. In proposing his idea for an online business, he aroused negative emotions among the managers. They worried that the future online business would cannibalize their existing business. And they felt happy about the present state, meaty profits from that existing business.

Telford spoof reversed those emotions, rendering his bosses fearful about the current state (falling behind the competition) and joyful about the prospect of keeping existing customers and adding revenues from new online customers. Now their emotions lined up in Telford’s favor, and they supported his proposal. Of course, the prank was borderline unethical, and as such it sparked an additional emotion that risked getting out of hand: anger–at him.

Show It (Don’t Just Tell)

Yet “showing, not telling” is by no means a common tactic. Only 18 percent of people in our 5,000-person dataset scored high on the statement, “frequently taps into people’s emotions to get them excited about their work.” That’s too bad. As our study also revealed, arousing emotional responses gets results, including for junior people. In fact, about 19 percent of people in either a senior job position (division manager) or a junior one (technical specialist) scored very high on their ability to stir emotions.

Make Them Feel Purpose

You can also use purpose to inspire other people so that they will commit to your projects and goals.

If you make people feel the purpose, they will try that much harder to help you achieve your goals.

Smart Grit

Grit at work is not about putting your head down and bulldozing through successive walls of resistance. Smartgrit involves not only persevering but also taking into account the perspective of people you’re trying to influence and devising tactics that will win them over.

Empathize With Your Opponents

In his book Power, Stanford Business School professor states that “putting yourself in the other’s place is one of the best ways to advance your own agenda.” He notes, however, that our obsession with our own concerns and objectives prevents us from doing so. We assume that opponents just don’t “get it,” and thus we pummel them with more facts and arguments in an effort to make them get it. That’s working hard, not smart.

Mobilize People (Don’t Go It Alone)

It’s better to enlist even just a few people to help convince others. In our study, some managers and employees rallied emissaries; 29 percent scored high on the statement, “She/he is very effective in mobilizing people to make change happen.” Ian Telford scored a 7 (highest) on this statement. As you’ll remember, he mobilized his boss to get an urgent meeting with the new top brass, Bob Wood, to plead for his Venture. He didn’t Advocate alone. As our data showed, those like Telford who mobilized people performed better (the correlation between the mobilization aspect and performance was a high 0.66).

Chapter 7: Fight And Unite

The Bay of Pigs disaster stands as a monument to a horrible team decision-making process. As the leader of the group, President Kennedy failed to foster a rigorous debate.

Having One Heck of a Fight

Two team meeting principles stood out among the rest. The first was something most of us don’t feel good about: fighting.

When teams have a good fight in their meetings, team members debate the issues, consider alternatives, challenge one another, listen to minority views, scrutinize assumptions, and enable every participant to speak up without fear of retribution.

Unite

Becht chuckled. “That’s exactly what happened. They said, ‘Nobody is leaving until we take a decision.’”

Once teams discussed issues, they achieved closure and moved quickly. If a Reckitt Benckiser team couldn’t decide within a reasonable period of time, the senior person in the room, usually the chair, made the final call. Every meeting ended with a judgment that was acted upon–fast. “You’re through and out the other side at the speed of light–and then on to the next one,” one executive said of meetings at the company.

Everyone also committed to implementing the decision. No second-guessing or political maneuvering would transpire in the hallways to undermine a path already chosen. “I think it [politics] is poison,” Becht said about the tendency to undermine decisions.

Reckitt Benckiser performed so well in part because so many of its managers and employees not only fought but also united.

In teams that unite, team members commit to the decision taken (even; if they disagree), and all work hard to implement the decision without second-guessing or undermining it.

We find similar teamwork cultures at other high performance companies. At Amazon, the company expects managers and employees to “challenge decisions when they disagree, even when doing so is uncomfortable or exhausting” and “once a decision is determined, they commit wholly.” Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen described how his company’s investment team debates when a partner proposes a deal. “It’s the responsibility of everyone else in the room to stress test the thinking,” Andreessen says. Whenever [partner Ben Horowitz] brings in an idea, I just beat the s— out of him. And I might think it’s the best idea I’ve ever heard, and I’ll just, like, trash the crap out of it. Ad I’ll get everybody else to pile on.” If the partner prevails, they will stop arguing. “We’ll say, ‘OK, we’re all in, we’re all behind you.’”

Seek Diversity, Not Just Talent

To fight better, try to bring in people with more diverse backgrounds and viewpoints.

If you’re a participant, you don’t necessarily get to pick who’s on your team or who gets invited into the conference room. Still, you can inject diversity by seeking out viewpoints and information from different places. Go consult peers who are not part of the team. Find that new market report that no one has bothered to consult. Seek out the “crazy” engineer who always has a contrarian thought. Then bring these different viewpoints to the next team meeting, either by inviting those people or presenting their views.

Make it Safe

There was also a toy horse, which people could toss at a speaker who was blathering on for too long–as in “beating a dead horse.”

Speak Up (Correctly)

Of the following four mindsets you might have during a team discussion, only one advances debate. Can you identify which?

- “I am here just to listen”

- “I want to sell people hard on my idea”

- “I am completely impartial in meetings”

- “I advocate my ideas” margin note: 4 is starred

Good performers also don’t show up behaving like an impartial academic (“on one hand I think… on the other hand I think…”). You’re also not there to sell your ideas. What matters isn’t whether your suggestions get accepted. It’s whether the team can generate the best possible solution, which may or may not involve your solution.

CIA Deputy Richard Bissell didn’t understand this point when discussing the Bay of Pigs invasion. He thought that his job was to get his plan approved, when in reality it was to help the group get to the best decision. Bisell later confessed, “So emotionally involved was I that I may have let my desire to proceed override my good judgment on several matters.”

Ask Nonleading Questions

Like Ham, people have a confirmation bias, asking for information that supports what they want to hear. Ham got her answer, even though the engineers remained uncertain about the state of the foam damage (which, as it turned out, was the cause of the disaster). In the hearings following the accident, she came under heavy criticism for her inability to probe the issue:

“As a manager, how do you seek out dissenting opinions?”

“Well, when I hear about them…”

“But Linda, by their very nature you may not hear about them.”

“Well, when somebody comes forward and tells me about them.”

“But Linda, what techniques do you use to get them?”

She did not reply.

People who crave to learn the truth about an issue don’t ask leading questions. They ask open-ended questions–inquiries that do not convey an opinion or bias. Ham would have been better off putting her query this way: “What’s your view on the foam damage?” Or she could have asked, “Does someone have a different point of view?” Or: “Can someone argue the opposite point of view?”

Make It Fair, Then Commit

The first requirement to get people to commit, then, is to make sure everyone on the team has a chance to express their opinions and that people consider and discuss them. Then people will be more likely to commit to a decision, even if they disagree with it.

Sharpen the Team Goal

In many teams, personal goals and infighting prevail because the team lacks a compelling, common goal. Team members retreat into their own individual interests, and before too long, team unity dissolves. You can unite a team by sharpening the team goal.

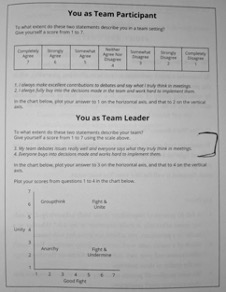

You as Team Leader: To what extent do these two statements describe your team?

Give yourself a score from 1-7 using the scale above.

3. My team debates issues really well and everyone says what they truly think in meetings.

4. Everyone buys into decisions made and works hard to implement them.

Chapter 8: The Two Sins of Collaboration

Sticks in a bundle are unbreakable. –Kenyan proverb

Two Bad Extremes of Collaboration

It’s hard enough to work well within teams, as we saw in the last chapter. But with entrenched silos, many individuals struggle as well to collaborate across boundaries. By collaborating I mean connecting with people in other groups, obtaining and providing information, and participating in joint projects. Those groups include other teams, divisions, sales offices, departments, geographic subsidiaries, and business units.

Ding! Teams with minuscule experience in either the topic of the bid or the client’s industry benefited from outside help. That was obvious–after the fact, of course! By contrast, teams with deep expertise fared worse when receiving input from colleagues. The more help they received, the lower their chances of winning the sales bid. These teams spent precious time searching for experts and, later, trying to incorporate their advice. They wound up dealing with more conflict and produced more chaotic, less effective sales proposals. These teams overcollaborated, because no compelling reason existed for them to seek outside help.

Why did smart, seasoned professionals request help from colleagues across the firm when they didn’t need it? Interviewing individual consultants, we learned that they felt pressure to collaborate. “There’s a norm around here that you ought to collaborate,” they told us. “If you don’t ask for help, it can count against you.” And so they collaborated, even though they lacked a compelling reason. They applied an old-fashioned “work harder” approach to collaboration, exerting extra effort to obtain and incorporate knowledge, aiming for quantity of collaboration, not quality. As a result, they did worse.

In the study for this book, we found plenty of instances in which overcollaboration compromised performance. Connor, a 31-year old marketing analyst in a Minnesota retail company, grumbled that “people from other business units constantly ask me for help on trivial things, which prevents me from focusing on my task at hand.” That lack of focus in turn caused him to disappoint his bosses.

First Ask, Why Collaborate?

Mike undertook the first, fundamental step in disciplined collaboration: building a clear, rigorous business case. Not every collaboration is beneficial. (margin note: EMTS) During my years studying collaboration in companies, I’ve found that few people instinctively build business cases for potential collaborations. That’s unfortunate: Our study confirmed the strong relationship between selective collaboration and performance.

Calculate the Premium

How precisely do you build a “business case”–a compelling reason–for a proposed collaboration? The following equation from my research and consulting provides a useful guide: Collaboration Premium = Benefit of Initiative – opportunity costs – collaboration costs

The First Rule of Disciplined Collaboration: Establish a compelling “why-do-it” case for every proposed collaboration. If it’s not compelling, don’t do it and say “no.”

Get Them Excited

Why might people prove unwilling to collaborate with you? One major reason is the lack of a unifying goal. What could the project managers have done differently? They could have articulated a compelling unifying goal, such as “grow combined market share in food by 50% in 3 years.” That’s a common goal that could excite each sales force to work toward winning in the market place together. That more comprehensive goal helped unify the interests of the two business units. Such unifying goals are powerful because they ask people to subordinate their individual interests to the common good.

Second Rule of Disciplined Collaboration: Craft a unifying goal that excites people so much that they subordinate their own selfish agendas. But beware: not all unifying goals will help. Based on my two decades of studying and Advising on unifying goals, I have identified four qualities that can guide you to make them effective. Try to make them common, concrete, measurable, and finite. The key to incorporating these four qualities is to concretize what is vague. Don’t say, “Our objective is to fight malaria in the world.” Say, “We want zero deaths from malaria in 20 years,” and then track the number of deaths by country.

Reward (Yes, But What?)

Be careful about how exactly you frame incentives. I often see people trying to reward collaboration activities, not results. Many managers know whether people participate in collaborative activities such as task forces, committees, and joint visits to customer sites. And so people check the box–”yes, did show up for that community meeting.” When you reward activities, that’s what you get–lots of collaboration activities. This leads to overcollaboration and people working long hours and evenings. Activities are just that–activities–and not accomplishments. What counts is results.

Third Rule of Disciplined Collaboration: Reward people for collaboration results, not activities.

Fourth Rule of Disciplined Collaboration: Devote full resources (time, skills, money) to a collaboration. If you can’t, scale it back or scrap it.

Engineer Trust, Fast

As we’ve seen, Mike’s effort with the LC triple quad illustrates all five disciplined collaboration rules: he established a compelling business case (and was prepared to ditch it if it wasn’t good enough). He set forth a compelling unifying goal of “$0 to $150 million in 3 years.” He aligned incentives well, especially by assigning all the revenues to the life sciences unit. He made sure the project was fully resources (money, skills, time). And he used trust boosters to build confidence that collaborators would commit to their shared goal.

The Goal of Collaboration is Not Collaboration

The goal of collaboration isn’t collaboration. It’s better performance.

Part 3: Mastering Your Work-Life

Chapter 9: Great at Work… And at Life, Too

Then, to achieve some semblance of a personal life, we go back in and erect a protective shield around our lives to protect work from crushing them. We switch off the smart phone at home, or refrain from checking email when watching our kids baseball games, or leave work early on certain days–all to prevent work from burying our private lives. Such measures only serve to treat the “symptom”–the result of working too much–and not the root cause, the work itself.

It turns out that the way to achieve both better performance and better well-being isn’t to put in more hours and then buttress your personal life with ironclad boundaries. It’s to concentrate on working smarter. Work on how you work, not on protecting your life from your work.

How Do You Really Get Better Work-Life Balance?

Two practices did improve work-life balance, most notably “Do less, then obsess.” When you narrow your scope of work and jettison less important tasks, you free up time that you can spend outside work. More disciplined collaboration can also improve work-life balance. People who collaborate stand to benefit from the help they receive, allowing them to work less. Meanwhile those who discipline their collaboration don’t get roped into unnecessary working groups and nighttime conference calls. They minimize the extra time required to collaborate, reducing the chances that work will bog down their private lives.

How Do You Prevent Burning Out?

The Mayo Clinic defines job burnout as a “special type of job stress–a state of physical, emotional or mental exhaustion combined with doubts about your competence and the value of your work.”

How Do You Enhance Your Job Satisfaction?

As for job satisfaction, our last well-being factor, four out of our seven practices enhance this benefit, two of them strongly. Passion and purpose loom large.

In our study, people who redesigned their job tasks also felt much more satisfied, perhaps because they got a chance to work on more valuable activities, or because they appreciated the autonomy or discretion they had to reimagine their role.

Don’t Take It Personally–And Don’t Fight Nasty

Don’t shy away from “mental” fights in meetings, but be sure to fight in the right way. As we discussed in chapter seven, don’t make your fighting in team meetings personal, and don’t take the comments cast in your direction personally, either. Avoid inflammatory language (“that’s a stupid idea”), because such toxic language upsets people. Likewise, when other people make disputes personal in a meeting, try to reorient them. One great tactic is to get more objective, highlighting impersonal data, facts, and numbers as opposed to emotion-laden opinions. Another is to play the “devil’s advocate”, a tactic that reduces interpersonal conflict by allowing you to play a role rather than speaking for yourself (“for the sake of argument, I am going to disagree”). Make fights about ideas, not people. The quality of your debates will improve, The emotional conflict will subside, and your sense of well-being will be better.

Work Smarter, Not Harder

If someone has emerged as a superstar, we assume that he or she works harder than everyone else. Yet the idea that working harder–longer hours–beyond some threshold will yield superior performance is flawed. The best performers don’t work harder. They work smarter. They maximize the value of their work by choosing a few priorities and applying targeted, intense effort to excel.

He goes on to explain: “I would have picked fewer petty fights with my peers in the organization, because I would have been generally more centered and self-reflective. I would have been less frustrated and resentful when things went wrong, and required me to put in even more hours to deal with a local crisis. In short, I would have had more energy and spent it and smarter ways… AND I would have been happier.”

Let’s learn from Moskovitz’s experience. And let’s learn from our study of 5,000 people drawn from many industries and all kinds of jobs, senior and junior. We can all become great at work–and in life–by working smarter, not harder. Focus on just seven core practices (and three tactics to improve well-being). Understand them. Apply yourself to these seven. Master them. Your performance will likely improve, and you’ll feel less stressed and more fulfilled. One day, you might even noticed something strange and wonderful happening. You know that colleague who outperforms everyone else, yet mysteriously leaves the office at a decent hour at the end of every day? The Natalie that I mentioned in chapter one and whom I encountered while working at the Boston Consulting Group in London?

That could be you.

Epilogue: Small Changes, Big Results

In chapter two (“Do Less, Then Obsess”), we saw that the best performers chose a few key areas to work on and then obsessed to excel in those. They went narrow and deep, not broad and shallow. Of course, sometimes you must cut out substantial areas of work–a big project, a large customer, or even a job–to get to that level of intense focus. But just as often, small changes–one-by-one–can free up enough time to do less and obsess. Start by learning to say “no” to new request for your time. Give yourself a buffer – the next time someone asks you for something, respond with, “Let me think about it, and I will get back to you tomorrow.” In the meantime, ask your spouse or a colleague to play the role of naysayer for you. Why might committing to the request be a bad idea? What do you have to lose by taking on the additional work?