Getting to yes. Negotiating agreement without giving in.

Rodger Fisher—2011.

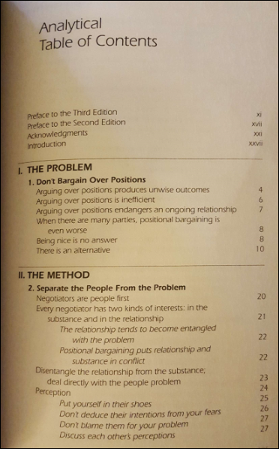

Chapter 1: don’t bargain over positions.

- These four points define a straightforward method for negotiation that can be used under almost any circumstance. Each point details the basic elements of negotiation, and suggests what you should do about it.

- People: separate the people from the problem.

- Interests: focus on interests, not positions.

- Options: invent multiple options looking for mutual gains before deciding what to do.

- Criteria: insist that the result be based on some objective standard.

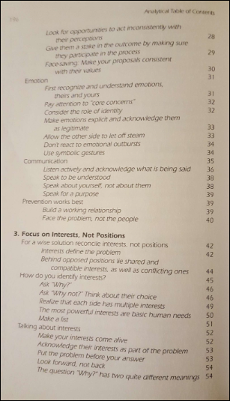

Chapter 2: the method. Separate the people from the problem.

- Whatever else you are doing at any point during a negotiation, from preparation to follow up, it’s worth asking yourself, “am I paying enough attention to the people problem?)

- As useful as looking for objective reality can be, it is ultimately their reality as each side sees it that constitutes the problem in a negotiation and opens the way to a solution.

- Put yourself in their shoes. How you see the world depends on where you sit. People tend to see what they want to see. Out of a mass of detailed information, they tend to pick out of focus on those facts that confirm their prior perceptions and to disregard or misinterpret those that call their perceptions into question. Each side in a negotiation may see only the merits of this case, and only the faults of the other side.

- Often in a negotiation people will continue to hold out not because the proposal on the table is inherently unacceptable, but simply because they want to avoid the feeling or periods of backing down to the other side.

- Allow the other side to let off steam. Often, one effective way to deal with people’s anger, frustration and other negative emotions is to help them release those feelings. People obtain psychological release through the simple process of recounting their grievances to an attentive audience. If you come home wanted to tell your husband about everything that went wrong at the office, you will become even more frustrated if he says, “don’t bother telling me, I’m sure you had a hard day. Let’s skip it.” The same is true for negotiators.

- If you pay attention and interrupt occasionally to say, “Did I understand correctly that you are saying…?” The other side will realize that they are not just killing time, not just going through a routine. They will also feel the satisfaction of being heard and understood. It has been said that the cheapest concession you can make to the other side is to let them know that they have been heard.

- Many consider it a good tactic not to give the other side’s case too much attention, and not to admit any legitimacy in their point of view. A good negotiator does just the reverse.

- Speak about yourself, not about them. In many negotiations, each side explains and condemns at great length the motivations and intentions of the other side. It is more persuasive, however to describe Apollo in terms of its impact on you that in terms of what they did or why: “I feel let down” instead of “you broke your word.” “We feel discriminated against” rather than “you are a racist.” If you make a statement about them that they believe is untrue, they will ignore you or get angry, they will now focus on your concern. But a statement about how you feel is difficult to challenge.

- Benjamin Franklin’s favorite technique was to ask and adversary if he could borrow a certain book. This would flatter the person to give him the comfortable feeling of knowing that Franklin owed him a favor.

Chapter 3: focus on interests, not positions.

- Your position is something you have decided upon. Your interests are what caused you to so decide.

- People listen better if they feel that you have understood them. They tend to think that those who understand them are intelligent and sympathetic people whose opinions may be worth listening to. So if you want the other side to appreciate your interests, begin by demonstrating that you appreciate theirs.

- If you want someone to listen and understand your reasoning, give your interests and reasoning first and your conclusions or proposal later.

- Often the wisest solutions, those that produce the maximum gain for you at the minimum cost to the other side, are produced only by strongly advocating your interests. To negotiators, each pushing hard for their interests, will often simulate each other’s creativity in thinking up mutual advantageous solutions.

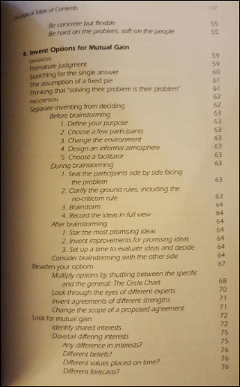

Chapter 4: invent options for mutual gain.

- One lawyer we know attributes his success directly to his ability to invent solutions advantageous to both his client and the other side. He expands the pie before dividing it. Skill at inventing options is one of the most useful assets of negotiator can have.

- Thinking that “solving their problem is their problem”.

- Ask for their preferences. One way to dovetail interests is to invent several options all equally acceptable to you and ask the other side which they prefer.

- Since success for you in a negotiation depends upon the other sides making a decision you want, you should do what you can to make that decision an easy one.

- Few things facilitate a decision as much as a precedent. Search for it. Live for decision are statement that the other side may have made in a similar situation, and try to base a proposed agreement on it.

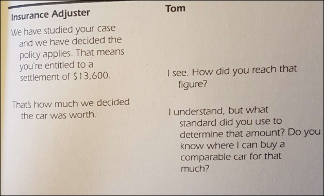

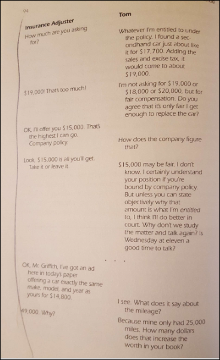

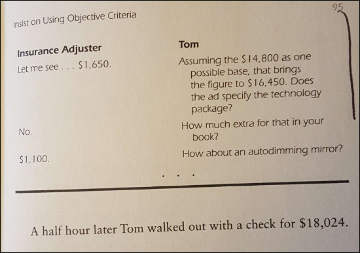

Chapter 5: insist on using objective criteria.

- Agree first on principles. Before even considering possible terms, you may want to agree on the standard or standards to apply.

- Each standard the other side proposes becomes a lever you can then the used to persuade them. Your case will have more impact if it is presented in terms of their criteria, and they will find it difficult to resist applying their criteria to the problem. “You say Mr. Jones sold the house next door for $260,000. You three is that this house should be sold for what comparable houses in the neighborhood are going for, am I right? In that case, let’s look at what the house on the corner of Ellsworth and Oxford and the one at Broadway and Dana were sold for.” What makes conceiving particularly difficult is having to accept someone else’s proposal. If they suggest the standard, they’re deferring to it is not an active weakness but an active strength, of carrying out their word.

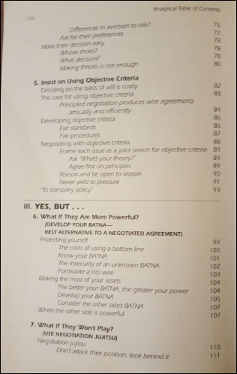

Chapter 6: what if they are more powerful?

- The bottom line also inhibits imagination. It reduces the incentive to invent a tailor-made solution that would reconcile differing interests in the way more adventitious for both you and them. Most every negotiation involves more than one variable. Rather than simply selling your place for $260,000, you might serve your interests better by settling for $235,000 with a first refusal on resale, a delayed closing, the right to use the barn for storage for two years, and an option to buy back 2 acres of the pasture. If you insist on the bottom-line, you’re not likely to explore and an imaginative solution like this. Bottom line—by its very nature rigid— is almost certain to be too rigid.

- In short, while adopting a bottom line may protect you from accepting a very bad agreement, it may keep you both from inventing and from agreeing to a solution it would be wise to accept. And arbitrarily selected figure is no measure of what you could or should accept.

- Know your BATNA. When a family is deciding on the minimum price for the house, the right question for them to ask is not what they “ought” to be able to get, but what they will do if by a certain time they have not sold the house. They keep it on the market indefinitely? Fully rented, terraced down, turned the land into a parking lot, let someone else live in it rent-free on condition they will paint it, or what? Which of those alternatives is most attractive, all things considered? And how does that alternative compare with the best offers seat for the house? It may be that one of those alternatives is more attractive than selling the house for $260,000. On the other hand, selling the house for as little as $224,000 may be better than holding onto indefinitely. It is most likely that any arbitrarily selected bottom-line truly reflects the family’s interests.

- The reason you negotiate is to produce something better than the results you can obtain without negotiating.

- Whether you should or should not agree on something in a negotiation depends entirely upon the attractiveness to you of the best available alternative.

- The better your BATNA, the greater your power. People think of negotiating power as being determined by resources like wealth, political connections, physical strength, friends and military might. In fact, the relative negotiating power of two parties depends primarily upon how attractive to each is the option of not reaching agreement.

- Develop your BATNA. Vigorous exploration of what you will do if you do not reach agreement can greatly strengthen your hand. Attractive alternatives are not just sitting there waiting for you, you usually have to develop them.

Chapter 7: what if they want to play?

- Ask questions and pause. Those engaged in negotiation jujitsu used to key tools. The first is to use questions and set of statements.

- Silence is one of your best weapons. Use it. If they have made an unreasonable proposal or an attack you regard as unjustified, the best thing to do may be to sit there and not say a word.

- Silence often creates the impression of a stalemate that the other side will feel compelled to break by answering a question or coming up with new suggestion.

Chapter 8: what if they use dirty tricks?

- Such tricky tactics are illegitimate because they failed that test of reciprocity.

- First, recognize the tactic as a possible negotiating ploy: an attempt to use their entry to negotiation as a bargaining chip to obtain some concession on substance. A variant on this ploy is to set preconditions for negotiation.

- Bringing the tactic to their attention works well here. Ask for principal justification on their position until it looks ridiculous even to them.

In conclusion.

- In 1964 an American father and his 12-year-old son were enjoying a beautiful Saturday in Hyde Park, London, and playing catch with a Frisbee. Few in England had seen a Frisbee at that time and a small group of strollers gathered to watch the strange sport. Finally, one Englishman came over to the father: “sorry to bother you. Been watching you a quarter of an hour. Who’s winning?”

- In most instances to ask a negotiator who’s winning, is as inappropriate as to ask who’s winning a marriage.

10 questions people ask about getting to yes.

- Urban police negotiators have learned that their act personal dialogue with criminals who are holding hostages frequently results in the houses is being released and the criminals taken into custody.

- Almost 60% of face-to-face negotiations result in mutually beneficial agreements, while only 22% did in written interactions and 38% and telephone negotiations. Meanwhile, when in half of the written interactions resulted in impasse, while only 19% of the face-to-face talks and 14% of the telephone negotiations did.

- Who should make the first offer? It would be a mistake to assume that making an offer is always the best way to put a figure on the table. Usually you will want to explore interests, options and criteria for a while before making an offer. Making an offer too soon can make the other side feel railroaded. Once both sides have a sense of the problem, and offer that makes an effort to reconcile the interests and standards that have been advanced is more likely to receive as a constructive step forward.

- Consider crafting a framework agreement. In negotiations that will produce a written agreement, it is usually a good idea to sketch the outlines of what an agreement might look like as part of your preparation. Such a “framework agreement” is a document in the form of an agreement, but with blank spaces for each term to be resolved by negotiation.

- As discussed in Chapter 8, recognizing a tactic or move allows you to name and begin an explicit negotiation over process. Another way to “change again” is to change the frame. In other words, the focus in the negotiation from positions to interests, options or standards. If the other side says, for example, “$10,000 is the most will pay,” when you think $50,000 would be fair, you could respond in several ways:

- Reframed to interests: “I hear that is your position. Given how far that seems below the market price, I may understand your interests. A experiencing a serious cash flow crisis?”

- Reframed two options: “$10,000 is one option, just as $100,000 or $200,000 would be attractive options from our point of view. I think we’ll get a lot further brainstorming options likely to be acceptable and attractive to both of us. What if we were to…?”

- Reframed to standards: “you must have good reason for thinking $10,000 is a fair offer. How did you arrive at that number? Why that number, instead of say, zero dollars or $100,000? My understanding is that the market price is $50,000. Why should we agree on less?”

- Reframed to BATNA: “of course, that’s your decision to make, and perhaps someone else will accept that. I think we need to think hard about whether an agreement is possible here that would make sense for both of us.”

- There is power in understanding interests. The more clearly you understand the other side’s concerns, the better able you will be to satisfy them at minimum cost to yourself. Look for intangible or hidden interests that may be important. With concrete interests like money, ask what lies behind them. (“For what will the money be used?”).

- Consider the sealed bid stamp auction. The auctioneer would like bidders to offer the most they might conceivably be willing to pay for the stamps in question. Each potential buyer, however does not want to pay more than necessary. In a regular sealed bid auction each bidder tries to offer slightly more than their best guess of what others will bid, which is often less than the bidder would be willing to pay. But in the stamp auction the rules state that the highest bidder gets the stamps at the price of the second-highest bid. Buyers can now safely bid exactly as much as they would you willing to pay to get the stamps, because the auctioneer guarantees that they will not have to pay it! No bidders left wishing that he or she had bid more, and the higher bidder is happy to pay less than was offered. The auctioneer’s happy knowing that the difference between the highest and second-highest bid is usually smaller than the overall increase in the level of bids under this system versus a regular sealed bid auction.