Engine of Impact: Essentials of Strategic Leadership in the Nonprofit Sector

William F. Meehan III and Kim Starkey Jonker

Foreword

- Your mission must be clear and focused.

- You must develop a strategy rooted in the few strategic concepts that matter most.

- You must figure out how to count what counts to ensure impact.

- You must have insight and courage, bringing heart and soul to making and executing on hard decisions.

- You must build a superb organization, a team of teams, that exemplifies the principles of high-performing organizations.

- You must attend to money, as cash flow is like oxygen to breathe, by crafting a strategic revenue machine that includes the right donors.

- You must achieve exceptional governance, building and nurturing a strong board that works.

Introduction: Strategic Leadership in the Impact Era

- Nonprofits, for instance, provide approximately 70 percent of all inpatient community-hospital care, and they serve about 30 percent of all students enrolled in four-year collegiate institutions or in postbaccalaureate programs. In addition, nonprofits account for a large portion of the cultural programming provided by museums, theaters, and various performing arts groups. Moreover, even as US politics become ever more strident and divisive, Americans still come together to donate their money and time to charitable organizations that provide a range of essential human services, including foster care for children in need; support for the hungry, the homeless, and the disabled; nursing-home services for the elderly; and more.

The Impact Era (2005 to the Present):

The Sector Reckons with New Challenges

- First, although information is now plentiful, donors still lack access to useful impact evaluation data. Nonprofits still rarely use rigorous, fact-based evaluation as the basis for decision making, and they share evaluation data even less often. Donors then default to a friendly recommendation, their own intuition, or deceptive measures of efficiency. Charity Navigator is almost certainly the most popular online source of nonprofit evaluation, but its ratings are largely driven by expense ratios (yes, still) – even though sloppiness or inattentiveness to costs is only a relatively small limitation to impact in the sector. Of course costs count, but credible measures of impact are what matter first and foremost. Second, donors still give mostly in emotional response to a fundraising request. Strategic philanthropy, based on in-depth impact evaluations, affects only a few discussions rather than most decisions.

The Need for Increased Philanthropy

- There is nothing new about this starvation cycle. The most cogent summary is offered in “The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle,” an article by Ann Goggins Gregory and Don Howard, who cite “funders’ unrealistic expectations,” “underfed overhead,” and “misleading reporting” as the driving factors in this cycle. Whatever the root causes, the solution is more generous and more flexible funding by foundations and individuals. If investment returns decline meaningfully in the future, perpetual foundations will struggle to meet their federally required 5 percent payout. Universities, museums, and other nonprofits that have grown accustomed to similar payout levels will also find that they face new challenges.

Part 1: Strategic Thinking: Build and Tune Your Engine of Impact

Chapter 1: The Primacy of Mission

The Danger of Mission Creep

- While some – though not us – might argue that vagueness is more inspiring that concreteness, vagueness and its companion, breadth, are inarguable antithetical to focus, a core tenet of strategy. Indeed, when students in Bill’s course conduct interviews at their chosen nonprofits, they often discover that many stakeholders do not even know their organization’s mission, let alone understand or feel any degree of passion or personal commitment toward it.

Focus Beats Diversification

- Unfortunately, many nonprofit organizations today are unfocused, and diversification in the sector is far too common. “Would you characterize your organization’s program activities as focused or diversified?” Margin note: ask us

A Tale of Three Mission Statements

- Mills suggested replacing the verb provide, which is used by 68 percent of nonprofit websites, with the verb better, which appears on only 0.1 percent of nonprofit websites.

The Exceptions That Prove the Rule

- Inextricable linkages in unmet needs. Every nonprofit must ask if the various needs that it seeks to address are both interrelated and inextricably linked.

- Relatedness, with overlapping core competencies. Another core issue is whether the proposed program areas are not only related but also mutually reinforcing.

- Lack of other organizations that have better skills.

- Extraordinary talent and unusually strong capacity to execute.

“Mission” Versus “Vision” and “Values”

- A recent trend has emerged in which nonprofits develop separate statements explaining their mission, their vision, and their values. We, unsurprisingly, believe that mission must be primary. Our against-the-grain view is that nonprofit organizations should stop spending so much time on vision and values statements, and funders should stop requesting and expecting that nonprofits include such information in grant requests. A mission statement is critical for a nonprofit – but vision and values statements are not. When mission, vision, and values statements are all included in a single communication, stakeholders are apt to loses sight of what is most important.

Mind Your Mission

- “Does this new opportunity align with our mission?” What is our organization’s mission? Do you think our organization is staying focused on this mission? Would you characterize our organization’s current programs and activities as broad or focused? Do you think we are experiencing mission creep? Should we alter our mission? If so, what do you believe our mission should be, and why?

Chapter 2: The Few Strategic Concepts That Matter

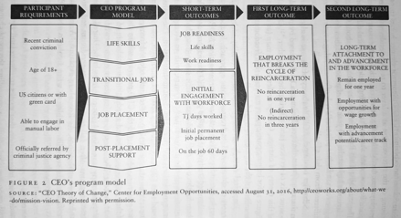

Theory of Change: Tying M ission to Strategy

- We see the notion of theory of change as posing these fundamental questions: How are you planning to achieve your mission? Is there empirical evidence that makes you think your chosen approach will work? A theory of change can take a wide variety of forms. In the simplest form, the essential theory underlying an intervention may be distilled into a sentence or two; the most complex form might include graphical pictures using boxes and arrows to diagram how various assumptions, activities, strategies, and expected outcomes fit together and how an intervention will succeed. Numerous helpful resources have been prepared by experts in the field to provide organizations with guidance in developing theories of change. These include resources from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, the Aspen Institute’s Roundtable on Community Change, the Foundation Center’s GrantCraft, and Grantmakers for Effective Organizations.

Landesa

- Land is the most critical resource for a majority of the world’s poorest people.

- The lack of secure and equitable land rights is a root cause of global poverty and gender inequality.

- Secure land rights provide a foundation for economic opportunity and better living conditions.

- Law is a powerful and highly leveraged tool for social and economic change.

- A small group of focused professionals working collaboratively with governments and other stakeholders can help to change and implement laws and policies that provide opportunity to the world’s poorest women and men.

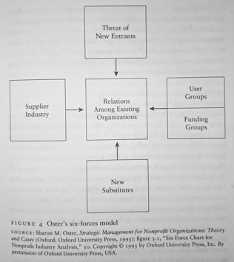

Oster’s Six Forces Model: Assessing a Nonprofit’s Competitive Position

The San Francisco Symphony: The Limits of Earned Revenue

- The quality of high-end performing arts organizations – and that of elite research universities and museums – will be shaped significantly by how much money they can raise, particularly for their endowments, and by the return on endowment investments. Many such organizations still resist or deny this truth, but they would do far better to confront it head-on – for it is a matter not of hopes and dreams but of economics and strategy.

Chapter 3: Count What Counts

Use Evaluation to Create a Loop to Drive Strategic Thinking

This logic begins with mission – “the what and the why” of an organization, or in other words, its purpose. A nonprofit ideally starts with a clear and focused mission that is aligned with its skills and capacity; this mission is typically unchanging. The mission will in turn shape the organization’s theory of change and its overall strategy. As we explained earlier, a theory of change sets for the “logic of how.” It describes how the organization will achieve its mission – and it incorporates evidence about why the theory works or can work.

Be Early, Be Managerial, and Consider External Evaluators

Measuring for management frees organizations from trying to attain the unattainable goal of perfection. “We look for organizations where if something goes wrong, they would know about it, and they would highlight it, and they would learn from it,” Elie Hassenfeld of GiveWell told the Huffington Post. “If you’re hearing some bad news, that’s a good thing. If you’re only hearing good news, that’s a bad thing. You should hold organizations accountable to that standard rather than a totally unreasonable one of perfection.

Share and Share Alike

GiveDirectly provides a compelling example of such transparency.

Part 2: Strategic Management: Fuel Your Engine of Impact

Chapter 6: Money Matters: Funding as Essential Fuel

Article: “Ten Nonprofit Funding Models” by William Landes Foster, Peter Kim, and Barbara Christiansen

Start with Your Board

Once you set out to improve your board’s giving and leadership in fund-raising activities, you will likely find low-hanging fruit. You might start by developing an accurate picture of what your board has done in this area to date. Our clients have found it useful to conduct sanitized (meaning: all names removed!) aggregated analyses that draw on both qualitative assessments and quantitative data and to discuss those analyses with their board. (We provide examples of such analyses on the website for this book.)

While there is no magic number for board giving, and expectations vary by organization, as a general rule board members should give at a personal stretch level and should prioritize your organization within their charitable giving.

Go Where the Money Is

Nonprofit leaders… should start by recognizing that most of the money in US philanthropy comes from individuals – not from foundations or corporations.

“I see churn rates as high as 40 percent to 50 percent, which is, in my view, egregious and unacceptable. Invariably, my first piece of advice to these organizations is to stop looking for new donors and first figure out how to keep the ones you have!”

Master the Ask

An important element of making the ask is connecting your organization’s needs with an opportunity for donors to make a significant difference. Shell explained: “I often twist the famous quote of Tip O’Neill [speaker of the US House of Representatives during the 1970s and 1980s], ‘All politics is local,’ into ‘All philanthropy is personal.’ In the realm of major gift support, donors have to see themselves in those large gift commitments that they are considering and believe that through their gift they are making a difference – ‘changing lives and changing the world,’ as we all like to say… Making a positive difference in the world remains one of humankind’s greatest desires. Connecting prospective donors’ hopes, dreams, and aspirations with the needs of your organization can be amazingly rewarding for both donor and organization. It is oftentimes where the magic occurs.

In a survey conducted by Burk, 93 percent of donors said they would be likely to give again if they (1) were thanked promptly and in a personal way for their gift and (2) received meaningful information about the program they funded. The best fund rasiers always assume that the first gift is never the last gift.

Chapter 7: Board Governance: Do What Works

Boards must insist that their organization conduct impact evaluations, and funders must be more willing to pay for them.

Chapter 8: Scaling: Leveraging the Seven Essentials to Magnify Your Impact

Readiness to Scale

We have designed a readiness-to-scale matris (shown in Figure 8) that we believe will not only assist nonprofit leaders in their high-level thinking but also serve as a robust managerial tool. The matrix includes five boxes – five categories that indicate how ready an organization is to scale – and we have designed visual and verbal metaphors to make these categories richly memorable. On our website, we provide a straightforward tool that you can use to evaluate your nonprofit organization (or any other) in terms of the four dimensions of strategic thinking (mission, strategy, impact evaluation, and insight and courage) and the three dimensions of strategic management (organization and talent, funding, and board governance). But here we focus on high-level definitions of the five categories.

Conclusion: Strategic Leadership: Now Is the Time

Nonprofit Board Members

- What is our organization’s mission? Is it clear and focused?

- What is our organization’s theory of change, and what is the resulting strategy? Is the theory of change logically sound? Is it supported by empirical evidence?

- Does our organization’s impact evaluation support the theory of change and the resulting strategy? Does it do so cost-effectively?