Time Talent Energy: Overcome Organizational Drag & Unleash Your Team’s Productive Power

Michael Mankins, Eric Garton

Prologue: The Truly Scarce Resources

Strategy is the art and science of resource allocation.

Financial capital is abundant and cheap. Our colleagues in the Bain Macro Trends Group estimate that total global capital has more than tripled over the past two decades and now stands at roughly ten times global GDP. As capital has grown more plentiful, its price has plummeted. For many large companies, the after-tax cost of borrowing is below the rate of inflation, meaning that the real borrowing costs hover close to zero. Indeed, any reasonably profitable enterprise can readily obtain the capital it needs to buy new equipment, fund new product development, enter new markets, or even acquire new businesses. To be sure, executive teams need to manage capital as carefully as ever; to do otherwise is to shoot yourself in the foot. But right now, the allocation of financial capital is no longer a source of competitive advantage.

What are today’s scarce resources, the new sources of competitive advantage? For most companies, the truly scarce resources are the time, talent, and energy of their people, and the ideas those people generate and implement.

Even when a company minimizes this drag, it may deploy and team its talent in ways that undermine performance. Maybe, for instance, it spreads its top talent evenly throughout the organization rather than concentrating it where it can have the greatest impact on strategy and performance. This egalitarian approach to talent management may appear fair, even admirable, but it rarely leads to great results. iIt also fails to take full advantage of the force multiplier that great teams can bring to idea generation and implementation.

“Whose company is it?” and the audience responds, “Ours!”

Chapter 1: An Organization’s Productive Power – and How to Unleash It

But when you spend time inside the steel-and-glass offices of most large corporations, an entirely different phenomenon strikes you. Forget lightning, internet time, and all the other metaphors of speed. Here, things move slowly. Meetings drag on….. But their output, the actual work they get done, is far less than it should be.

We think of that something as organizational drag, a collection of institutional factors that interfere with productivity yet somehow go unaddressed. Organizational drag slows things down, decreasing output and raising costs. Organizational drag saps energy and drains the human spirit. Organizational drag interferes with the most capable executive’s or employee’s efforts, encouraging a “What’s the use?” attitude. While the level varies, nearly every company we’ve studied loses a significant portion of its workforce’s productive capacity to drag. It’s time for companies to confront this productivity killer head on.

Quantifying the possibilities

This deficit may in fact be significantly more than 20 percent. In our work with clients, for example, we typically find that 25 percent or more of the typical line supervisor’s time is wasted just in unnecessary meetings or e-communications.

Beyond the raw mix, however, we found that the best-performing companies focused their best talent in a few critical roles. In essence, these companies have more “difference makers” and they assign these exceptional individuals to roles where they will have the biggest impact on the company’s performance.

In short, the outliers recognize that teaming is more important than simply bringing in great talent, because most work gets done in teams.

How productive is your organization?

For a full diagnostic of your company, please visit our website: www.timetalentenergy.com

Talent

5. How effective is your organization at identifying the company’s difference makers and placing them in roles where they can make the greatest difference?

6. In your experience, when your organization has launched a new initiative that was critical to business success, how has it approached forming a team to drive the initiative?

Part One: Time

Chapter 2: Liberate the Organization’s Time

By the numbers: How organizational time is squandered

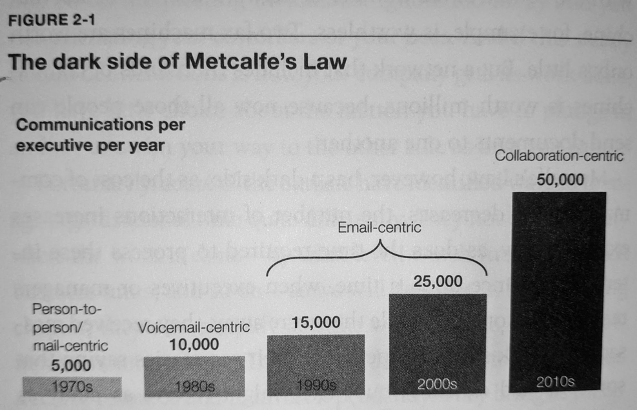

Dysfunctional meeting behavior is on the rise. Meeting participants at most of the organizations we examined routinely sent emails during meetings.

Such demands on the organization’s time typically undergo no review and require no formal approval. For example, leaders at one large manufacturing company recently discovered that a regularly scheduled ninety-minute meeting of mid-level managers cost more than $15 million annually. When asked “Who is responsible for approving this meeting?” the managers were at a loss. “No one,” they replied. “Tom’s assistant just schedules it at the team attends.” In effect, a junior vice president’s administrative assistant was permitted to invest $15 million without supervisor approval. No such thing would ever happen with the company’s financial capital.

How to manage your organization’s time

1. Invest time as carefully as you invest money

Be ruthless in setting priorities. When Steve Jobs was leading Apple, he would take the company’s top one hundred executives off-site for a planning retreat, where he pushed them to identify the company’s top ten priorities for the coming year. Members of the group competed intensely to get their ideas on the short list. Then Jobs liked to take a marker and cross out the bottom seven. “We can only do three,” he would announce. His gesture made it clear what the executives should and should not focus on.

Beginning each hour long meeting only five minutes late costs a company 8 percent of its meeting time. Most management teams wouldn’t tolerate 8 percent waste in any other area of responsibility.

3. Take a holistic approach

It’s tough to implement reforms like these piecemeal, because people will tend to forget about them. That’s why we often recommend a major companywide effort to change meeting practices. The Australian energy company Woodside offers an example.

Chapter 3: Simplify the Operating Model

Revenge of the nodes

As the number of nodes proliferates, so does the number of interactions it takes to get work done. In a 2015 study, the research and advisory firm CEB found that more than 60 percent of employees now must interact with ten or more people every day to do their job; 30 percent must interact with twenty or more. These percentages have increased consistently over the last five years. CEB also found that between 35 percent and 40 percent of managers “are so overloaded [by collaboration] that it’s actually impossible for them to get work done effectively,” according to researcher Brian Kropp.

Part Two: Talent

Chapter 5 looks at talent from another angle. Steve Jobs probably said it best: “Great things in business are never done by one perseon, they’re done by a team of people.” But how much attention does the typical company pay to assembling and managing its teams? In our experience, far too little. Executives are likely to make up a team from whoever happens to be available and then wonder why it doesn’t accomplish much. The best performers, by contrast, take a far more disciplined approach to teaming. These companies form all-star teams, as we’ll describe in this chapter. If you need to get something done, done quickly, and done right, the chances are you will need a team of A-level players.

Here, too, we’ll have some stories to tell and some controversies to stir up. We’ll offer several telling examples to illustrate how much better “the best” really are. We’ll show why the conventional nine-box assessment of managers’ performance and potential is close to useless. We’ll show why NASCAR driver Kyle Busch can win so many races, how Boeing filled a critical gap in its product lineup faster than ever before, and how Ford and Dell turned themselves around partly by paying attention to teaming.

Pretty much every company knows it should have as many great people as it can find. But if all that talent isn’t to wither on the vine – if those great people instead continue to develop, to make an impact, and to work productively with other great people – they have to be managed as the scarce resource they are. That’s where you make a difference.

Margin note: teams

Chapter 4: Find and Develop the “Difference Makers”

1. Determine where your difference makers can make the biggest difference

Why – and where – the CEO has to be involved

So ask yourself: Can you list the 100 to 150 most critical positions in your organization,

given your business model, strategy, assets, and capabilities? Who are the 100 to 150 difference makers in your company? Are they in these roles?

Part Three: Energy

No one ever washes a rental car.

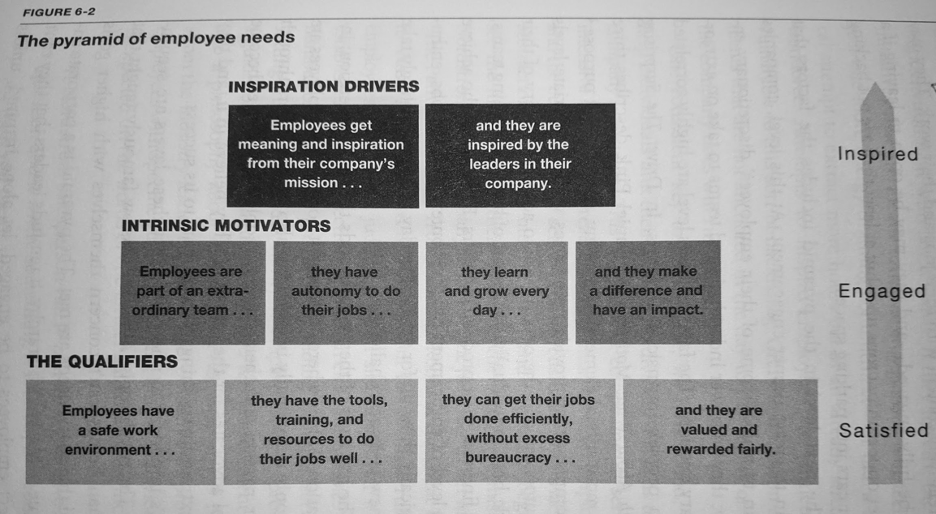

Unless you feel real ownership – real connection – you will never devote the extra energy needed to make something better. The same is true in business. Unless your employees feel engaged, even inspired, by the work they are doing, they will not invest their discretionary energy in the company, its customers, or its success.

In this part of the book, we introduce the third factor affecting performance. As it turns out, organizational energy is the single most powerful factor we measured, raising the average company twenty-four points on the productivity index.

Chapter 6: Aim for Inspiration (Not Just Engagement)

Inspiration is contagious, so they also inspire those around them to strive for greater heights. In the workplace, as one pundit put it, employees react differently when they encounter a wall. Satisfied employees begin looking around for ladders to scale the wall. Inspired employees just break right through it.

2. Balance employee autonomy with organizational needs

Central to any model of engagement and inspiration in modern, dynamic companies is the concept of employee autonomy; indeed, autonomy may be the single most important element in creating engagement or inspiration in any company.

3. Develop leaders who deliver results and inspire

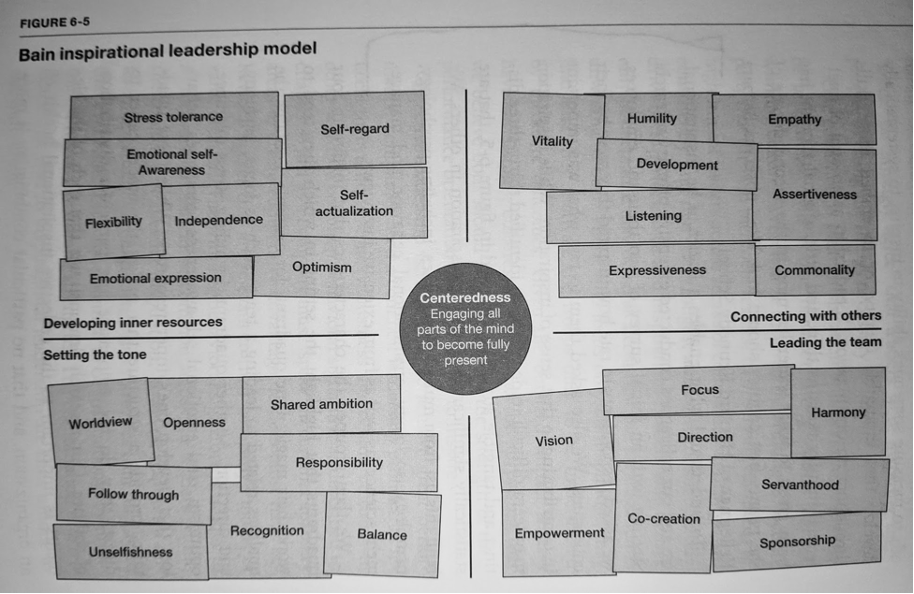

To understand what enables a leader to be inspirational, we and our colleagues conducted extensive primary research. Starting with an initial survey of two thousand employees, we asked respondents to rate how inspired they were by their colleagues. We also asked them to rate what was important in contributing to that sense of inspiration. While inspiration may seem difficult to decipher, we identified thirty-three distinct and tangible attributes, depicted in figure 6-5, that are statistically significant in creating inspiration in others. We built this list from multiple disciplines, including psychology, neurology, sociology, organizational behavior, and management science, as well as from extensive interviews.

- Everyone has the ability to become inspiring by focusing on his or her strengths as opposed to fixing weaknesses. This is consistent with a growing body of research. According to Gallup, for example, the odds of employees being engaged are 73 percent when an organization’s leadership focuses on the strengths of its employees, compared to 9 percent when they do not.

A surprising result of the research was that centeredness turned out to be the single most important attribute among the thirty-three. It was the most statistically significant in creating inspiration, and it was the trait that employees most want to develop. Centeredness is a state of greater mindfulness, achieved by engaging every part of the mind. While a growing number of companies offer optional mindfulness programs to promote health and workplace satisfaction, our research shows that centeredness is fundamental to the ability to lead. It improves one’s ability to stay level-headed, cope with stress, empathize with others, and listen more deeply.