Work Rules! Insights From Inside Google That Will Transform How You Live And Lead

Laszlo Bock

Preface: A Guidance Counselor’s Nightmare

Most CEOs are very good at many things, but they become CEOs for being superbly distinctive at one or two, which tend to be matched to a company’s needs at that time. Even CEOs need to declare a major. Welch is best known for Six Sigma – a set of tools to improve quality and efficiency – and his focus on people.

Why Google’s Rules Will Work For You

A billion hours ago, modern Homo sapiens emerged.

A billion minutes ago, Christianity began.

A billion seconds ago, the IBM personal computer was released.

A billion Google searches ago… was this morning.

– Hal Varian, Google’s Chief Economist, December 20, 2013

But the default leadership style at Google is one where a manager focuses not on punishments or rewards but on clearing roadblocks and inspiring her team.

So what did? Performance improved only when companies implemented programs to empower employees (for example, by taking decision-making authority away from managers and giving it to individuals or teams), provided learning opportunities that were outside what people needed to do their jobs, increased their reliance on teamwork (by giving teams more autonomy and allowing them to self-organize), or a combination of these. These factors “accounted for a 9% increase in value added per employee in our study.” In short, only when companies took steps to give their people more freedom did performance improve.

All it takes is a belief that people are fundamentally good -0 and enough courage to treat your people like owners instead of machines. Machines do their jobs; owners do whatever is needed to make their companies and teams successful.

Chapter 1: Becoming a Founder

You are a founder

Building an exceptional team or institution starts with a founder. But being a founder doesn’t mean starting a new company. It is within anyone’s grasp to be the founder and culture-creator of their own team, whether you are the first employee or joining a company that has existed for decades.

The fundamental lesson from Google’s experience is that you must first choose whether you want to be a founder or an employee. It’s not a question of literal ownership. It’s a question of attitude.

Student or senior executive, being part of an environment where you and those around you will thrive starts with your taking responsibility for that environment. This is true whether or not it’s in your job description and whether or not it’s even permitted.

Chapter 2: “Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast”

A mission that matters

Second, Google’s mission is distinctive both in its simplicity and in what it doesn’t talk about. There’s no mention of profit or market. No mention of customers, shareholders, or users. No mention of why this is our mission or to what end we pursue these goals. Instead, it’s taken to be self-evident that organizing information and making it accessible and useful is a good thing.

This kind of mission gives individuals’ work meaning, because it is a moral rather than a business goal.

Crucially, we can never achieve our mission, as there will always be more information to organize and more ways to make it useful. This creates motivation to constantly innovate and push into new areas. A mission that is about being “the market leader,” once accomplished, offers little more inspiration.

… people see their work as… a calling (a source of enjoyment and fulfillment…)

Once it’s explained, ti seems self-evident. But how many of us have taken the time to look for deeper meaning in our work? How many of our companies make a practice of giving everyone, especially those most remote from the office, access to your customers so employees can witness the human effect of their labors? Would it be hard to start?

If you believe people are good, you must be unafraid to share information with them

One of the serendipitous benefits of transparence is that simply by sharing data, performance improves. Dr. Marty Makary, a surgeon at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, points to when New York State started requiring hospitals to post death rates from coronary artery bypass surgeries. Over the next four years, deaths from heart surgery fell 41 percent. The simple act of making performance transparent was sufficient to transform patient outcomes.

All of us want control over our destinies

In 2009, Googlers told us through our annual survey that it was becoming harder to get things done. They were right. We had doubled in size, growing to 20,222 employees by the end of 2008 from 10,674 at the end of 2006, and growing to $21.8 billion in revenues from $10.6 billion. But rather than announcing top-down corporate initiatives, our CFO, Patrick Pichette, put the power in TGooglers’ hands. He launched Bureaucracy Busters, a now-annual program where Googlers identify their biggest frustrations and help fix them. In the first round, Googlers submitted 570 ideas and voted more than 55,000 times. Most of the frustrations came from small, readily addressable issues: The calendar application didn’t allow groups to be added, so large meetings took forever to set up; budget approval thresholds were annoyingly low, requiring managers to review even the smallest transactions; time-saving tools were too hard to find (ironic). We implemented the changes Googlers asked for, they were happier, and it actually became easier to do our work.

In contrast, I recall a discussion with an HR leader from one of the ten biggest companies in the country. “Our CEO wants us to be more innovative,” she said. “He asked me to call you because Google is known for having an innovative culture. One of his ideas is to set up a ‘creativity room’ where we have a foosball table, bean-bags, lava lamps, and lots of snacks, so people can come up with crazy ideas. What do you think? How does Google do it?”

I told her a big about how Google’s culture really works, and suggested that perhaps her CEO could try videotaping his staff meetings and sharing the recordings with people so they could see what’s going on in the company and what’s important to their leaders. I was just floating a crazy idea, but I thought it might be a powerful way to share with employees how decisions were made. I didn’t know at the time that Bridgewater was thinking even bigger, taping every meeting. “No,” she countered, “we’d never do that.” How about having junior people attend leadership team meetings as notetakers, and they could then be vectors for that knowledge across the company? (Jonathan Rosenberg, our former SVP of Product, pioneered this for us.) “No, we couldn’t share that information with junior people.”

Hmm… okay. How about, when the CEO does employee meetings, seeding the audience with the tough, provocative questions that people are afraid to ask? “Oh no, he would never do that. Think of all the crackpot emails he’d get.” A different angle was to have a suggestion box – which she thought might work – and then each quarter let a self-nominated group of employees decide what suggestions to implement. And maybe even give them a budget for it? “Oh no, that won’t work. Who knows what they might do?”

This otherwise remarkable company was afraid of giving employees even the tiniest opportunity for direct expression and dialogue with their CEO. At which point I wished her luck with the beanbags and lava lamps.

If you give people freedom, they will amaze you

So, to my astonishment, the phrase “culture eats strategy for breakfast” was pretty spot-on.

Margin note: Why we need learn culture

Chapter 3: Lake Wobegon, Where All the New Hires Are Above Average

There are examples of people who were mediocre performers and went on to greatness, though most of those successes are a result of changing the context and type of work, rather than a benefit of training.

Companies continue to invest substantially more in training than in hiring, according to the Corporate Executive Board.

Chapter 4: Searching for the Best

It really did start with the founders

The founders realized it was important to hire by committee, often interviewing candidates together while sitting around the ping-pong table, which doubled as our only conference table. They intuited that no individual interviewer will get it right every time, an instinct that would later be formalized in our “wisdom of the crowds” study in 2007, which we’ll discuss shortly.

The early days: hiring astounding people at a snail’s pace

Like everyone else, we did reference checks, but we also built an applicant tracking system that would check a candidate’s resume against the resumes of existing Googlers. If there was overlap – say you went to the same school in the same years as a Googler, or worked at Microsoft at the same time – the Googler would often get an automated email asking if they knew you and what they thought of you.

That’s an issue at Google, where we look for people who can not only solve today’s problems, but can also solve whatever unknown problems may come up in the future.

But in 2010, our analyses revealed that academic performance didn’t predict job performance beyond the first two or three years after college, so we stopped requiring grades and transcripts except from recent graduates.

Oops – our employees don’t know everyone in the world

Our overreliance on referrals had simply started to exhaust Googlers’ networks. In response, we started introducing “aided recall” exercises. Aided recall is a marketing research technique where subjects are shown an ad or told the name of a product and asked if they remember being exposed to it. For example, you might be asked if you remember seeing any laundry detergent commercials in the past month. And then you might be asked if you remember seeing any Tide commercials. A little nudge like that always improves people’s recollections.

In the context of generating referrals, people tend to have a few people who are top of mind. But they rarely do an exhaustive review of all the people they know (though one Googler referred her mother – who was hired!), nor do they have perfect knowledge of all the open jobs available. We increased the volume of referrals by more than one-third by jogging people’s memories just as marketers do. For example, we asked Googlers whom they would recommend for specific roles: “Who is the best finance person you ever worked with?” “Who is the best developer in the Ruby programming language?” We also gathered Googlers in groups of twenty or thirty for Sourcing Jams. We asked them to go methodically through all of their Google+, Facebook, and LinkedIn contacts, with recruiters on standby to follow up immediately with great candidates they suggested. Breaking down a huge question (“Do you know anyone we should hire?”) into lots of small, manageable ones (“Do you know anyone who would be a good salesperson in New York?”) garners us more, higher-quality referrals.

Chapter 5: Don’t Trust Your Gut

A century of science points the way to an answer

The second-best predictors of performance are tests of general cognitive ability (26 percent).

In Margin: ?

Ties with tests of general cognitive ability are structured interviews (26 percent), where candidates are asked a consistent set of questions with clear criteria to assess the quality off responses. Structured interviews are used all the time in survey research. The idea is that any variation in candidate assessment is a result of the candidate’s performance, not because an interviewer has higher or lower standards, or asks easier or harder questions.

There are two kinds of structured interviews: behavioral and situational. Behavioral interviews ask candidates to describe prior achievements and match those to what is required in the current job (i.e., “Tell me about a time…?”). Situational interviews present a job-related hypothetical situation (i.e., “What would you do if…?”. A diligent interviewer will probe deeply to assess the veracity and thought process behind the stories told by the candidate.

My experience is that people who score high on conscientiousness “work to completion” – meaning they don’t stop until a job is done rather than quitting at good enough – and are more likely to feel responsibility for their teams and the environment around them. In other words, they are more likely to act like owners rather than employees. I remember being floored when Josh O’Brien, a member of our tech-support team, was helping me with an IT issue in my first month or so. It was a Friday, and when five o’clock rolled around I told him we could finish on Monday. “That’s okay. We work to completion,” he told me, and kept at it until my problem was resolved.

Examples of interview questions include:

- Tell me about a time your behavior had a positive impact on your team. (Follow-ups: What was your primary goal and why? How did your teammates respond? Moving forward, what’s your plan?)

- Tell me about a time when you effectively managed your team to achieve a goal. What did your approach look like? (Follow-ups: What were your targets and how did you meet them as an individual and as a team? How did you adapt your leadership approach to different individuals? What was the key takeaway from this specific situation?)

- Tell me about a time you had difficulty working with someone (can be a coworker, classmate, client). What made this person difficult to work with for you? (Follow-ups: What steps did you take to resolve the problem? What was the outcome? What could you have done differently?)

If you don’t want to build all this yourself, it’s easy enough to find online examples of structured interview questions that you can adapt and use in your environments. For example, the US Department of Veterans Affairs has a site with almost a hundred sample questions at www.va.gov/pbi/questions.asp. Use them. You’ll do better at hiring immediately.

Never compromise on quality

Having professionals do the initial remote evaluation also means that it’s possible to do a robust, reliable screening for the most important hiring attributes up front. Often a candidate’s problem-solving and learning ability is assessed at this stage.

Putting it all together: how to hire the best

In 2013, with roughly forty thousand people, the average Googler spent one and a half hours per week on hiring, even though our volume of hiring is almost twice what is was when we had twenty thousand people.

And it was thanks to Loren, who had been a Googler for give days and whom we trusted to make this encounter possible.

Chapter 6: Let the Inmates Run the Asylum

One of the challenges we face at Google is that we want people to feel, think, and act like owners rather than employees. But human beings are wired to defer to authority, seek hierarchy, and focus on their local interest. Think about meetings that you go to. I’d wager that the most senior person always ends up sitting at the head of the table. Is that because they race from office to office, scurrying to be the first so they can seize the best seat?

Watch closely next time. As attendees file in, they leave the head seat vacant. It illustrates the subtle and insidious nature of how we create hierarchy. Without instruction, discussion, or even conscious thought, awe make room for our “superiors.”

Managers have a tendency to amass and exert power.

Employees has a tendency to follow orders.

Eliminate status symbols

To be transparent, it’s become harder to hold this line as we’ve gotten bigger. Titles that we used to ban outright, like those containing the words “global” or “strategy,” have crept into the company. We had banned “global” because it’s both self-evident and self-aggrandizing. Isn’t every job global, unless it specifically says it isn’t? “Strategy” is similarly grandiose. Sun Tzu was a strategist. Alexander the Great was a strategist. Having been a so-called strategy consultant for many years, I can tell you that putting the word “strategy” in a title is a great way to get people to apply for a job, but it does little to change the nature of the work.

I explained how title should follow leadership. It was a red flag within the first few weeks when he asked, ‘But how can I get them to do what I want them to do if I don’t have the title?’ He lasted less than six months.”

Symbols and stories matter. Ron Nessen, who served as press secretary for President Gerald Ford, shared a story about his boss’s leadership style: “He had a dog, Liberty. Liberty has an accident on the rug in the Oval Office and one of the Navy stewards rushes in to clean it up. Jerry Ford says, ‘I’ll do that. Get out of the way, I’ll do that. No man ought to have to clean up after another man’s dog.’”

What makes this vignette so compelling is that the most powerful man in the United States not only understood his personal responsibility, but also appreciated the symbolic value of demonstrating it.

Make decisions based on data, not based on managers’ opinions

In 2010 alone, we conducted 8,157 A/B tests and more than 2,800 one-percent tests. Put another way, every single day in 2010 we ran more than thirty experiments to uncover what would best serve our users. And this was just for our search product.

We take the same approach on people issues. When we implemented our Upward Feedback Survey (a periodic survey about manager quality – more on this in chapter 8), we ran an A/B test to see if Googlers were more likely to give feedback to their managers if the email announcing the survey was signed by an executive of a generic “UFS Team” email alias. We saw no difference in response rates, so we opted to use the generic alias, simply because it’s easier to write one email than to ask each executive to write one of his or her own.

Almost any major program we roll out is first tested with a sub-group. I remember when we crossed twenty thousand employees and I was first asked if it bothered me that Google was now indisputably a big company. “We always worry about culture,” I responded, “but the virtue of big is that we can run hundreds of experiments to see what really makes Googlers happier.” Every office, every team, every project is an opportunity to run an experiment and learn from it. This is one of the biggest missed opportunities that large organizations have, and it holds just as true for companies made up of hundreds, not thousands. Too often, management makes a decision that applies unilaterally to the entire organization. WHat is management is wrong? What if someone has a better idea? What if the decision works in one country but not another? It’s crazy to me that companies don’t experiment more in this way!

Find ways for people to shape their work and the company

Googlegeist is distinctive because it is written not by consultants but by Googlers with PhD-level expertise in everything from survey design to organizational psychology, all results (both good and bad) are shared back with the entire company within one month, and it is the basis for the next year of employee-led work on improving the culture and effectiveness of Google. Every manager with more than three respondents gets a report, dubbed MyGeist. This report – which is actually an interactive online tool – allows managers to view and share personalized reports that contain a summary of the Googlegeist scores for their organizations. Whether their team is three or thirty Googlers strong, managers get a clear sense of how they’re doing according to their teams. With one click, managers can choose to share with just their direct teams, with their broader organizations, with a customized list of Googlers, or even with all of Google. And most do.

There’s a virtuous cycle here: We take action on what we learn, which encourages future participation, which then gives us an ever more precise idea of where to improve. We enable this cycle by defaulting to open: The reports of any vice president with a hundred or more respondents are automatically published to the entire company…

Critically, Googlegeist focuses on outcome measures that matter. Most employee surveys focus on engagement, which as Prasad Setty explains, “is a nebulous concept that HR people like but doesn’t really tell you much. If your employees are 80 percent engaged, what does that even mean?” The Corporate Executive Board found that “The meaning of employee engagement is ambiguous among both academic researchers and among practitioners… [The] term is used at different times to refer to psychological states, traits, and behaviors as well as their antecedents and outcomes.” Engagement doesn’t tell you precisely where to invest your finite people dollars and time. Do you increase it by focusing on health programs? On manager quality? On job content? There’s no way to know.

Googlegeist instead focuses on the most important outcome variables we have: innovation (maintaining an environment that values and encourages both relentlessly improving existing products and taking enormous, visionary bets), execution (launching high-quality products quickly), and retention (keeping the people we want to keep). For example, we have five questions that predict whether employees are likely to quit. If a team’s responses to those five questions fall below 70 percent favorable, we know more people will leave during the following year unless we intervene.

We ask Googlers to suggest fixes that would benefit lots of their colleagues and that we can implement within two or three months. In 2012, we received 1,310 ideas and over 90,000 votes on them.

Expect little from people, get little. Expect a lot…

All this adds up to happier people generating better ideas. The truth is that people usually live up to your expectations, whether those expectations are high or low. Edwin Locke and Gary Latham, in their 1990 book A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance, showed that difficult, specific goals (“Try to get more than 90 percent correct”) were not only more motivating than vague exhortations or low expectations (“Try your best”), but that they actually resulted in superior performance. It therefore makes sense to expect a lot of people.

In 1999 we were serving a financial services company and doing one of the first e-commerce projects our firm had ever done. (Remember “e-commerce”?) I brought a draft report to him and instead of editing it, he asked, “Do I need to review this?” I knew deep down that while my report was good, he would surely find some room for improvement. Realizing this, I told him it wasn’t ready and went back to refine it further. I came back to him a second time, and a second time he asked, “Do I need to review this?” I went away again. On my fourth try, he asked the same question and I told him, “No. You don’t need to review it. It’s ready for the client.”

What managers miss is that every time they give up a little control, it creates a wonderful opportunity for their team to step up, while giving the manager herself more time for new challenges.

Pick an area where your people are frustrated, and let them fix it. If there are constraints, limited time or money, tell them what they are. Be transparent with your people and give them a voice in shaping your team or company. You’ll be stunned by what they accomplish.

Chapter 7: Why Everyone Hates Performance Management, and What We Decided to Do About It

Throwing in the towel

The major problem with performance management systems today is that they have become substitutes for the vital act of actually managing people.

The focus on process rather than purpose creates an insidious opportunity for sly employees to manipulate the system.

In fact, no one is happy about the current state of performance management. WorldatWork and Sibson Consulting surveyed 750 senior HR professionals and found that 58 percent of them graded their own performance management systems as C or worse. Only 47 percent felt the system helped the organization “achieve its strategic objectives,” and merely 30 percent felt that employees trust the system.

Setting Goals

In addition, everyone’s Objectives and Key Results are visible to everyone else in the company on our internal website, right next to their phone number and office location.

Ensuring Fairness

Calibration diminishes bias by forcing managers to justify their decisions to one another. It also increases perceptions of fairness among employees.

Avoid defensiveness and promote learning with one simple trick

The answer: Do it in two distinct conversations.

Intrinsic motivation is key to growth, but conventional performance management systems destroy that motivation.

But introduce extrinsic motivations, such as the promise of promotion or a raise, and the willingness and ability of the apprentice to learn starts to shut down.

Never have the conversations at the same time. Annual reviews happen in November, and pay discussions happen a month later. Everyone at Google is eligible for stock grants, but those decisions are made a further six months down the line.

As Prasad Setty explains, “Traditional performance management systems make a big mistake. They combine two things that should be completely separate: performance evaluation and people development.

The wisdom of crowds… it’s not just for recruiting anymore!

In 2013, we also experimented with making our peer feedback templates more specific. Prior to that, we’d had the same format for many years: List three to five things the person does well; list three to five things they can do better. Now we asked for one single thing the person should do more of, and one thing they could do differently to have more impact. We reasoned that if people had just one thing to focus on, they’d be more likely to achieve genuine change than if they divided their efforts.

Chapter 8: The Two Tails

Put your best people under a microscope

In 2008, Jennifer Kurkoski and Brian Welle cofounded the People and Innovation Lab (PiLab), an internal research team and think tank with the mandate to advance the science of how people experience work.

Project Oxygen has had the most profound impact on Google. The name comes from a question Michelle once asked: “What if everyone at Google had an amazing manager? Not a fine one or a good one, but one that really understood them and made them excited to come to work each day.”

Google: The 8 Project Oxygen Attributes

- Be a good coach.

- Empower the team and do not micromanage.

- Express interest/concern for team members’ success and personal well-being.

- Be very productive/results-oriented.

- Be a good communicator – listen and share information.

- Help the team with career development.

- Have a clear vision/strategy for the team.

- Have important technical skills that help advise the team.

List of the 8 Project Oxygen attributes from Google. © Google, Inc.

The specific prescription for managers is to prepare for meetings by thinking hard about employees’ individual strengths and the unique circumstances they face, and then use the meeting to ask questions rather than dictate answers.

In addition to being specific, we had to make good management automatic. Atul Gawande has written persuasively in The New Yorker and in his book The Checklist Manifesto about the power of checklists.

But if we could reduce good management to a checklist, we wouldn’t need to invest millions of dollars in training, or try to convince people why one style of leadership is better than another. We wouldn’t have to change who they were. We could just change how they behave. Margin note: PMA

And if managers need help getting better in a specific area, and the checklist isn’t doing the trick, they can sign up for the courses we’ve developed over time for each of the attributes. Taking “Manager as Coach” improves coaching scores an average of 13 percent. Taking “Career Conversations” improves career development ratings by 10 percent, in part by teaching the manager to have a different kind of career conversation with employees. It’s not about having the Googler ask for something and the manager promise to deliver. Instead of a transactional exchange, it’s a problem-solving exercise that ends with shared responsibility. There’s work for both the manager and the Googler to do.

Managing your two tails

Have the people who are best at each attribute train everyone else. We ask our Great Manager Award recipients to train others as a condition of winning the award.

Chapter 9: Building a Learning Institution

You learn the best when you learn the least

Ericsson instead found that it’s not about how much time you spend learning, but rather how you spend that time. He finds evidence that people who attain mastery of a field, whether they are violinists, surgeons, athletes, or even spelling bee champions, approach learning in a different way from the rest of us. They shard their activities into tiny actions, like hitting the same golf shot in the rain for hours, and repeat them relentlessly. Each time, they observe what happens, make minor – almost imperceptible – adjustments, and improve. Ericsson refers to this as deliberate practice: intentional repetitions of similar, small tasks with immediate feedback, correction, and experimentation.

McKinsey – Engagement Leadership Workshop

Now reflect on the last training program you went to. Perhaps there was a test at the end, or maybe you were asked to work as a team to solve a problem. How much more would you have internalized the content if you’d been given specific feedback and then had to repeat the task three more times?

It’s a better investment to deliver less content and have people retain it, than it is to deliver more hours of “learning” that is quickly forgotten.

You can keep your team members’ learning from shutting down with a very simple but practical habit. I had the pleasure of working with Frank Wagner, who is now one of our key People Operations leaders at GOogle, in 1994, when we were consultants. In the minutes before every client meeting, he would take me aside and ask me questions: “What are your goals for this meeting?” “How do you think each client will respond?” “How do you plan to introduce a difficult topic?” We’d conduct the meeting, and on the drive back to our office he would again ask questions that forced me to learn: “How did your approach work out?” “What did you learn?” “What do you want to try differently next time?” I would also ask Frank questions about the interpersonal dynamic in the room and why he pushed on one issue but not another. I shared responsibility with him for ensuring I was improving.

Every meeting ended with immediate feedback and a plan for what to continue to do or change for next time. I’m no longer a consultant, but I often go through Frank’s exercise before and after meetings that my team has with other Googlers. It’s an almost magical way to continuously improve your team’s performance, and it takes just a few minutes and no preparation. It also trains your people to use themselves as their own experiments, asking questions, trying new approaches, observing what happens, and then trying again.

Build your faculty from within

Individual performance scales linearly, while teaching scaled geometrically.

You don’t even need to pull your best salesperson out of the field to make this work. If you break selling down into discrete skills, there may be different people who are best at cold-calling, negotiation, closing deals, or maintaining relationships. The best at each skill should be teaching it.

Former Intel CEO Andy Grove made the same point over thirty years ago: “Training is, quite simply, one of the highest-leverage activities a manager can perform. Consider for a moment the possibility of your putting on a series of four lectures for members of your department. Let’s count on three hours of preparation for each hour of course time – twelve hours of work in total. Say that you have ten students in your class. Next year they will work a total of about twenty thousand hours for your organization. If your training results in a 1 percent improvement in your subordinates’ performance, your company will gain the equivalent of two hundred hours of work as the result of your expenditure of your twelve hours.”

For example, Marty Linsky of Cambridge Leadership Associates has helped us build our Adoptive Leadership Curriculum, and Daniel Goleman helped develop our mindfulness programs.

As an experiment, in late 2013, I invited Googler Bill Duane, a former engineering leader turned Mindfulness Guru, to start my weekly staff meetings with the exercise. I wanted to experiment on ourselves first, and if it worked out we could then try it on large groups of Googlers, and perhaps eventually the whole company.

The first week was just listening to our breathing, the next was observing the thoughts that ran through our heads as we breathed, working up to paying attention to our current emotions and how they felt in our bodies. After a month, I asked my team if we should continue. They insisted that we did. They told me our meetings seemed more focused, more thoughtful, and less acrimonious. And even though we were spending time on meditation, we were more efficient and were finishing our agenda early each week.

Meng and Bill aren’t alone in deciding that the most important thing they could do – despite their outstanding work as specialists – was to teach. We have a broader program, galled G2G or Googler2Googler, where Googlers enlist en masse to each one another. In 2013, 2,200 different classes were delivered to more than 21,000 Googlers by a G2G faculty of almost three thousand people. Some classes are offered more than once, and some have more than one instructor. Most Googlers took more than one class, resulting in a total attendance of over 110,000.

Another tip: “To rid yourself of saying ‘umm’ during a presentation, use physical displacement. Every time you are transitioning, do something small but physical, like moving your pen. Making a conscious effort to move your pen will turn your brain off from using a verbal filler instead.”

Becky Cotton was our first official Career Guru, a person to whom anyone could turn for career advice. There was no selection process or training. She just decided to do it. She started by announcing in an email that she would hold office hours for anyone who wanted career advice. Over time, demand grew and others volunteered to join Becky as Career Gurus, and in 2013 more than a thousand Googlers had sessions with one of them.

Your homework

As a pragmatic matter, you can accelerate the rate of learning in your organization or team by breaking skills down into smaller components and providing prompt, specific feedback.

WORK RULES . . . FOR BUILDING A LEARNING INSTITUTION

⃞ Engage in deliberate practice: Break lessons down into small, digestible pieces with clear feedback and do them again and again.

⃞ Have your best people teach.

⃞ Invest only in courses that you can prove change people’s behavior.

Chapter 10: Pay Unfairly

Make it easy to spread the love

As Napoleon is purported to have written, though in a more sinister vein: “I Have made the most wonderful discover. I have discovered men will risk their lives, even die, for ribbons!” Simple, public recognition is one of the most effective and most underutilized management tools.

Chapter 11: The Best Things in Life Are Free (or Almost Free)

We use our people programs to achieve three goals: efficiency, community, and innovation. Every one of our programs exists to further at least one of these goals, and often more than one.

A community that spans Google and beyond

In 2007 we created our Advanced Leadership Lab, a three-day program for senior leaders where we deliberately assembled a diverse group, spanning a range of geographies, professional functions, genders, social and ethnic backgrounds, and tenures.

Fueling innovation

Amazon lists 54,950 books on innovation for sale.

Ronal Burt, a sociologist at the University of Chicago, has shown that innovation tends to occur in the structural holes between social groups. These could be the gaps between business functional units, teams that tend not to interact, or even the quiet person at the end of the conference table who never says anything. Burt has a delicious way of putting it: “People who stand near the holes in a social structure are at higher risk of having good ideas.”

People with tight social networks, like those in a business unit or team, often have similar ideas and ways of looking at problems. Over time, creativity dies. But the handful of people who operate in the overlapping space between groups tend to come up with better ideas. And often, they’re not even original. They are an application of an idea from one group to a new group.

Find a way to say yes

Chapter 12: Nudge… a Lot

Nudges are not mandates. Putting the fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not. In other words, nudges are about influencing choice, not dictating it.

At Google we apply nudges to intervene at moments of decision in myriad ways. Most of our nudges are applications of academic research in a real-world setting. Jennifer Kurkoski, a PhD member of our PiLab team, jokes that “Too much academic research is just the study of college sophomores. So many experiments are conducted by professors offering five dollars to undergrads to participate in a study.”

Our guiding principle? Nudges aren’t shoves. Even the gentlest of reminders can make a difference. A nudge doesn’t have to be expensive or elaborate. It only needs to be timely, relevant, and simple to put into action. Much of our work in this area falls under a program called Optimize Your Life, which is led byYvonne Agyei in partnership with Prasad Setty (People Operations), Dave Radcliffe (WorkplaceServices—he runs the shuttles and cafes, for example), and all of their teams. And Googlers, of course, are a great source of ideas and inspiration too.

Using nudges to help people become healthy, wealthy, and wise: wisdom first

Though not strictly a nudge, this was in line with work showing the power of social comparisons.

And this isn’t just a Google problem. Brad Smart, in Topgrading, found that half of all senior hires fail within eighteen months of starting a new job.

Kent’s secret: “I spent most of my time listening.” Most people joined eager to get things done. But without understanding how to get things done at Google, they struggled. I used to call it “the Google crisis,” a point about three or six months in when a new leader realized that the bottom-up, collaborative nature of our culture meant that they couldn’t just bark orders and expect people to fall in line. We now build this learning into the first week of orientation for Nooglers.

In the pilot, managers received just-in-time emails the Sunday before a new hire started. Like the Project Oxygen checklist, which showcased the eight behaviors of successful managers, the five actions were almost embarrassing in their simplicity:

1. Have a role-and-responsibilities discussion.

2. Match your Noogler with a peer buddy.

3. Help your Noogler build a social network.

4. Set up onboarding check-ins once a month for your Noogler’s first six months.

5. Encourage open dialogue.

And as with Project Oxygen, we saw a substantial improvement. Nooglers whose managers took action on this email became fully effective 25 percent faster than their peers, saving a full month of learning time.

We then had to make sure there were unambiguous steps the manager could take. Our people are smart but busy. It reduces cognitive load if we provide clear instructions rather than asking them to invent practices from scratch or internalize a new behavior, and this lowers the chance that an extra step might discourage them from taking action. Even the president of the United States limits the volume of things he needs to think about, so that he can focus on important issues, as he explained to Michael Lewis in Vanity Fair: “‘You’ll see I wear only gray or blue suits,’ [President Obama] said. ‘I’m trying to pare down decisions. I don’t want to make decisions about what I’m eating or wearing. Because I have too many other decisions to make.’ He mentioned research that shows the simple act of making decisions degrades one’s ability to make further decisions. It’s why shopping is so exhausting. ‘You need to focus your decision-making energy. You need to routinize yourself. You can’t be going through the day distracted by trivia.’”

At first blush all this specificity might seem a bit infantilizing, but in fact our managers told us it was liberating. Remember that not everyone is a born manager. By telling managers exactly what to do, we actually took one annoying item off their to-do list. They had less to think about and could focus instead on acting. The results recently moved a manager to shoot a quick thank-you note to the new-hire orientation team: “The operation you and your team have built is AWESOME! The email …with the onboarding information is emblematic of the entire experience. We really appreciate how easy you make this for us.”

That’s because when you design for your users, you focus on what is the minimal, most elegant product required to achieve the desired outcome. If you want people to change behavior, you don’t give them a fifty-page academic paper or *ahem* a four-hundred-page book.

Another challenge we had was that Googlers would often sign up for learning courses and then fail to attend. In the first half of 2012, we had a 30 percent no-show rate, which prevented Googlers on the waitlist from taking courses and caused us to run half-empty classes. We tried four different email nudges, ranging from appealing to our desire to avoid harming others (showing photos of people on the waitlist so enrollees could see who would be harmed by a no-show) to relying on identity consistency (reminding enrollees to be “Googley” and do the right thing). The nudges had the dual effect of reducing no-shows and increasing the rate at which people canceled their slots in advance, which allowed us to offer them to other Googlers. The effects of each nudge were different, however. Showing the photos of waitlisted enrollees increased attendance by 10 percent but did less to encourage unenrollment. Appeals to identity had the greatest effect on unenrollment, increasing it by 7 percent. Since then, we’ve incorporated these nudges into all course reminders and seen better attendance and shorter waitlists.

Using nudges to help people become healthy, wealthy, and wise: Mens sana in corpore sano

Thus far we’d seen that people liked having more options and information, but no one was behaving differently. So we turned to nudging, subtly changing the structure of the environment without limiting choice.

The idea was sparked by an article by David Laibson, a professor of economics at Harvard University. In his paper “A Cue-Theory of Consumption,” he demonstrated mathematically that cues in our environment contribute to consumption. We certainly eat because we’re hungry, but we also eat because it’s lunchtime or because people around us are eating. What if we removed some of the cues that caused us to eat?

Rather than take away sweets, we put the healthier snacks on open counters and at eye and hand level to make them more accessible and appealing. And we moved the more indulgent snacks lower on our shelves and placed them in opaque containers.

In our Boulder, Colorado, office we measured the consumption of micro kitchen snacks for two weeks to generate a baseline, and then put all the candy in opaque containers. Though the containers were labeled, it wasn’t possible to see the brightly colored wrappers. Googlers, being normal people, prefer candy to fruit, but what would happen when we made the candy just a little less visible and harder to get to?

We were floored by the result. The proportion of total calories consumed from candy decreased by 30 percent and the proportion of fat consumed dropped by 40 percent as people opted for the more visible granola bars, chips, and fruit. Heartened by the result, we did the same thing in our New York office, home to over two thousand Googlers. Healthy snacks like dried fruit and nuts were put in glass containers, and sweets were hidden in colored containers. After seven weeks, Googlers in our New York office had eaten 3.1 million (3,100,000!) fewer calories – enough to avoid gaining a cumulative885 pounds.

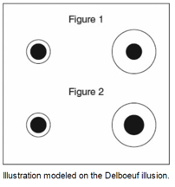

We turned to our cafés to see if a similar small nudge could change behavior. In a series of studies, Professors Brian Wansink (Cornell University) and Koert van Ittersum (Georgia Tech) demonstrated that serving-dish size has a powerful impact on food consumption. They cleverly illustrated the issue by referencing the Delboeuf illusion, an invention of Belgian philosopher and mathematician Joseph Delboeuf in the late 1860s. The illusion looks like this:

In figure 1, are the black circles the same size, or is one larger than the other? What about in figure 2?

In 1, even though the circle on the left looks larger, they are both the same size. In 2, even though the black circles look the same size, the one on the right is 20 percent larger. Now imagine the white circle is a plate, and the black is the food.

It turns out that in this case, seeing is believing. Our assessment of how much we eat and oursatiation are heavily shaped by the size of the serving dish. The bigger the dish, the more we eat and the less satisfied we feel.

The professors presented six studies, one of which considered breakfast at a health and fitness camp. The subjects were overweight teenagers, who had been taught about portion control and how to monitor consumption. Experts, right?

Not even close. Campers who were given smaller cereal bowls not only consumed 16 percent less than campers who received larger bowls, they thought they consumed 8 percent more than the large-bowl campers. They ate less but were more satisfied, despite having been trained in how to measure and pace their consumption.

Another study was conducted at an all-you-can-eat Chinese buffet, where Wansink and professor Mitsuru Shimizu (Southern Illinois State University) observed diners who were given the option of choosing a small or large plate. Both sets of diners were comparable, with no difference in gender mix, estimated age, estimated BMI, or the number of trips to the buffet. At this point you won’t be surprised to read that those who chose the bigger plate ate more. Fifty-two percent more, in fact. But they also wasted 135 percent more food, in part because they had larger plates that could hold more food, and because they left more of it on their plates.

The findings were intriguing enough that we wanted to try similar experiments at Google. Our primary goal was to improve Googlers’ health, but since our cafés are effectively buffet restaurants we also thought we might reduce waste.

But the studies’ samples were small and quite different from our workforce: 139 teenagers at camp and forty-three diners in the Chinese restaurant. Would the results hold for thousands of Googlers?

We selected one cafe and replaced our standard twelve-inch plates with smaller nine-inch plates. Sure enough, as we’d seen in other cases where we imposed a change without offering choice, Googlers got grumpy. “Now I have to get up twice to have lunch,” wailed one.

Then we reintroduced choice, offering both large and small plates. The complaining stopped. And 21 percent of Googlers started using the small plates. Progress!

And then we added information. We put up posters and placed informational cards on the cafe tables, referencing the research that people who ate off smaller plates on average consumed fewer calories but felt equally satiated. The proportion of Googlers taking small plates increased to 32 percent, with only a small minority reporting that they needed to go back for seconds.

How did the sample size compare? We served over 3,500 lunches in that cafe that week and reduced total consumption by 5 percent and waste by 18 percent. Not a bad return on the cost of a few new dishes.

Chapter 13: It’s Not All Rainbows and Unicorns

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds”

“A crisis is an opportunity to have impact. Drop everything and deal with the crisis.”

Chapter 14: What You Can Do Starting Tomorrow

- Give your work meaning.

- Trust your people.

- Hire only people who are better than you.

- Don’t confuse development with managing performance.

- Focus on the two tails.

- Be frugal and generous.

- Pay unfairly.

- Nudge.

- Manage the rising expectations.

- Enjoy! And then go back to No. 1 and start again.

Afterword for HR Geeks Only: Building the World’s First People Operations Team

I’d made an amateur mistake. Before Eric would entertain any esoteric ideas, People Operations had to deliver on Google’s most important issue. I learned that to have the privilege of working on the cool, futuristic stuff, you had to earn the confidence of the organization. In 2010, we enshrined that notion in a graphic that encapsulated our approach. The pyramid shape was a nod to psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which he presented as a pyramid with our most fundamental needs at the bottom (air, food, water), topped by the need for safety, belonging, love, and finally self-actualization. After seeing our version, a few folks from our team took to calling it Laszlo’s hierarchy.

The compensation team even developed a cheat sheet about each management member, describing how best to work with him or her, so that the new team members can work smoothly with our most senior leaders right from the start.

The french-fry graphic labeled “anticipation” needs a little explaining. I drew the name from an episode of the comedy 30 Rock. Set at NBC’s headquarters in Rockefeller Center, the show followed the cast and crew of a variety show, starring comedian Tracy Jordan (played by the real-life comedian Tracy Morgan). In one episode, Tracy is furious because his staff has brought him a hamburger, but failed to bring the fries he did not ask for: “Where are the french fries I didn’t order?! When will you learn to anticipate me?!”

When I first saw the episode, I thought Tracy was a hilarious monster of ego.

Then I realized he was right. He wasn’t a psycho. He was an executive!

People are happy when you give them what they ask for. People are delighted when you anticipate what they didn’t think to ask for. It’s proof that they’re wholly visible to you as people, not just as workers from whom you’re trying to squeeze productivity.

Anticipation is about delivering what people need before they know to ask for it. Thanks to 30 Rock, we call these instances of perfect anticipation “french fry moments.”

Ironically, our first executive development programs like the ones I had proposed to Eric in our initial meeting turned out to be a classic french fry moment. When Evan Wittenberg (then a member of our learning team and now SVP of People at Box, an online data-storage company), Paul Russell (an early leader of our learning team, now retired), and Karen May (at the time a consultant and our current VP of People Development) created Google’s first Advanced Leadership Lab in 2007, it was intensely controversial because Google at the time was organized by function – engineering, sales,finance, legal, for example – and the groups didn’t interact unless necessary.

Field an unconventional team

In too many companies, HR is where you park the nice people who aren’t delivering elsewhere.

There is little in this book that we could have accomplished without this combination of talent. In the HR profession, it is an error to hire only HR people.